- Details

- By Levi Rickert

HOPKINS, Mich. — When Robert “Dokmëgizhêk” Lewis, Ph.D., taught a Potawatomi language class in late July, he kept the attention of his students by inserting cartoon figures like Oscar, Daffy Duck, Sponge Bob, and the Cookie Monster into his slide presentation.

Lewis was teaching on how to say words for colors in Bodwéwadmimwen at the 2025 Language Conference in Hopkins, Michigan. The conference was held on the first day of the 2025 Pottawatomi Gathering hosted by the Match-E-Be-Nash-She-Wish Band of Pottawatomi, commonly known as the Gun Lake Tribe in West Michigan.

“Wénithë odë yawet? (Who is this?)" Lewis asked the class in Bodwéwadmimwen. The participants responded speaking in the Native language.

"Daffy Duck odë yawė. (This is Daffy)," Lewis continued.

"Wabshkezė nė o Daffy, mkedéwzė nė o Daffy, anaké zhë skëbgezė nė o Daffy? (Is Daffy white, is Daffy black, or is Daffy green)?" Lewis asked next.

The participants responded wirh "Éhé', mkedéwzė o Daffy."

"Yes, Daffy is black." Lewis proclaimed.

Lewis’ goal was to teach language learners how to say various colors in the Bodwéwadmimwen (Potawatomi language). In addition to using cartoon characters, Lewis provided attendees with the words for fruits and vegetables.

Lewis, a citizen of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation, teaches the Bodéwadmi language at the Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation. He was one of several instructors who taught some 700 participants at the Pottawatomi Gathering week.

The language conference consisted of breakout sessions, such as the one Lewis taught, and general assembly sessions where the participants heard about programs in Potawatomi tribal communities in various parts of the United States and Canada.

Since 1994, with the exception of during the COVID-19 pandemic,12 Potawatomi nations from the United States and Canada have gathered at one of their nations on a rotating basis. In 2004, two days at the beginning of the Gathering were added to give attendees the opportunity to learn about their Native language.

Indian Boarding Schools Attempted to Destroy Our Language

Native American languages were explicitly targeted for destruction by the federal government during the Federal Indian Boarding School era. Students who attended boarding schools were stripped of their culture and forbidden to speak their languages.

Sam Alloway, a tribal elder from the Forest County Potawatomi Nation, said the things he learned as a child are still with him like hunting, fishing, gathering, and traditional dancing. However, attending an Indian boarding school meant that he was unable to learn his traditional language.

“I'm a beginner speaking our language because I was placed at the boarding school when I was younger, so a lot of that is taken away, and my life is a little different. So learning the language kind of helped bring that culture back to me,” Alloway said.

Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation Chairman Joseph “Zeke” Rupnick, who sat in on a general session at the language conference, recalled that his mother was taken away from the reservation at age three and placed in a Catholic boarding school in Martin, S.D. When she returned home to the reservation, she refused to speak in her Native language.

Rupnick learned a few words in the Potawatomi language from his grandparents, who have both been gone for a long time now. He hopes efforts like the language conference will allow younger generations to forge a strong connection to their Native language.

“As you get older, you remember some of that stuff, of what they taught you,” Rupnick said. “I would hope that our kids would be able to learn our language because that really defines who we are. Everything that this world is, everything that moves in this world is defined by our language, and our language looks at every living thing out there and describes it in such a way that it's hard to even put it in English, and that's what I would hope that our kids yet to come will be able to experience.”

Western Institutions Hinder Native Language Learning

During the conference, Rhonda Purcell (Pokagon Band of Potawatomi), the director of her tribe’s Ėthë Bodwéwadmimwat (the Language and Culture Department), stated that Native people have become so involved with Western institutions that it is difficult for parents to teach their children their language.

“Our parents and individuals who are responsible for raising those children are so busy working that 40-hour-a-week job to maintain full-time status so that they can earn a living wage, if we can even call it that, at this point, and to be able to provide health benefits for their children. So that's taking them away from the house. And these kids after preschool or elementary school, they're going to these daycare institutions, and they're being parented after hours by somebody else, and not their own family member, who may have, you know, a semblance of knowledge of the language,” Purcell told Native News Online.

Purcell said language must be shared and taught within families, rather than being taught strictly in an educational setting.

“It also has to happen with the family at home. And right now, families can't do that because they're so busy working, trying to maintain that full-time status,” Purcell said.

For Purcell, learning the language is a lifelong journey. She recalls listening to words spoken by her late grandmother, who spoke Bodwéwadmimwen.

She says she understands now as an adult that her grandmother could express herself better in her Native language than in English. Purcell learned the language 15 years ago.

“My language learning journey did not take a pivotal step until I was pregnant with my firstborn, and that's when it really hit me that it's more than just feeding your kid and loving your kid,” Purcell said. “If you really want to give them the guidance in order to be a productive Potawatomi person, you need to give them what it means to be Bodéwadmi, that is the language.”,

“If we lose our language, the Creator will destroy the Earth”

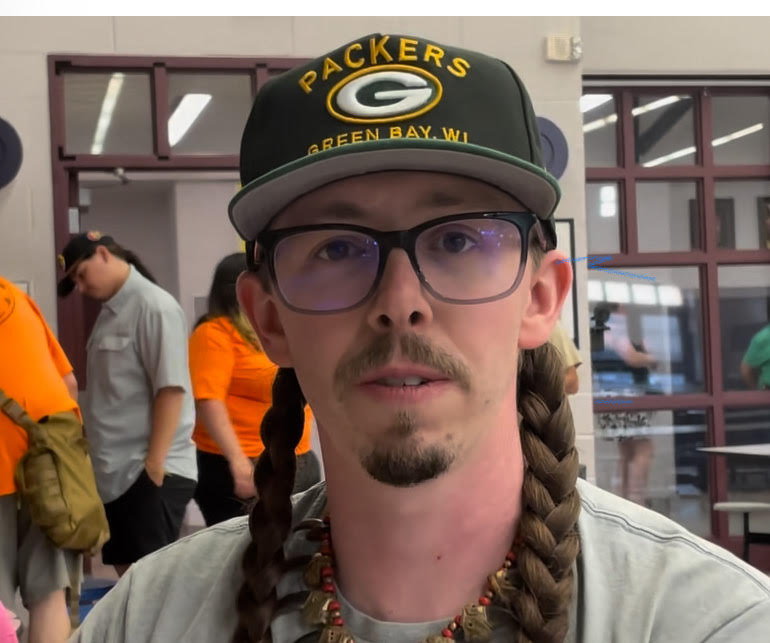

Kyle Mallot, a citizen of the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi, was one of the instructors at the conference. Mallot began learning the language 15 years ago and has been teaching it for 13 years.

In 2013, Mallot was chosen to participate in a four-year Potawatomi Master-Apprentice Language Program in Forest County, Wisc. During his studies, he deepened his study of Bodwéwadmimwen by learning directly from fluent speakers such as Jim Thunder, with support and additional opportunities provided by the Pokagon Band.

Mallot is currently an advanced language specialist at the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi, based in Dowagiac, Mich.

Mallot said learning the Bodéwadmi language has been life-changing.

“Learning the language changed my whole perspective on Earth, life, and everything,” Mallot told Native News Online. “Learning language made me feel connected to our culture. Our entire culture is built into our entire identity. When you learn our words, they have a deeper meaning. So, when you dive in, start to understand a lot more of how our people see the world and how we see life and different things like that, what we're supposed to, and you feel more complete as a person.”

Mallot emphasized that the Native identity and existence is rooted in language.

“We need to carry that on to the next generation. It's also said that if we lose our language, the Creator will destroy the Earth,” Mallot said.

Tribal Leaders Support Language

While many tribal leaders support language revitalization, resources are limited.

During panel discussions at the conference general assemblies, instructors, who wanted to remain anonymous, addressed reduced funding for language programs as a result of the Trump administration’s sweeping cuts across the federal government.

During one general assembly session, Purcell opined that tribal councils should fund language learning to the level that would allow parents to have reduced work weeks, thereby giving them the time to foster Native languages in their homes.

“Sometimes what we need the most is advocacy. We need advocates at tribal council meetings when we're asking for financial support. We see this as community,” Purcell said. “We know from personal testimonies that people have shared with us that language has provided them the stability and support to be able to make good decisions. It's given them guidance and direction in terms of helping to instill and fulfill that sense of identity that's been lacking.”

More Stories Like This

Chickasaw Lighthorse Police Officer named Indian Country Law Enforcement Officer of the YearIndian Gaming Association Rallies Broad Coalition Against Sports Event Contracts It Calls Illegal Threat to Tribal Sovereignty

Navajo Resources and Development Committee Issues Notice on Livestock Inspection Requirements

American Prairie, Tribal Coalition Files Protest Over Rescinded Grazing Rights

Northern Cheyenne Push Back Against Trump Administration’s Effort to Alter Little Bighorn History

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher