- Details

- By Stu Whitney, South Dakota News Watch

This article was originally published in South Dakota News Watch and is used with permission.

A recent court ruling that found South Dakota violated federal voting registration laws has reignited the long-standing concern over Native American ballot access as the state braces for a 2022 gubernatorial election that could hinge on Indian County precincts.

In a state with nearly 78,000 Indigenous residents, comprising 8.8 percent of the population, advocates of greater Native enfranchisement have worked to enlist new voters in areas such as the Pine Ridge and Rosebud reservations that lean left-of-center politically.

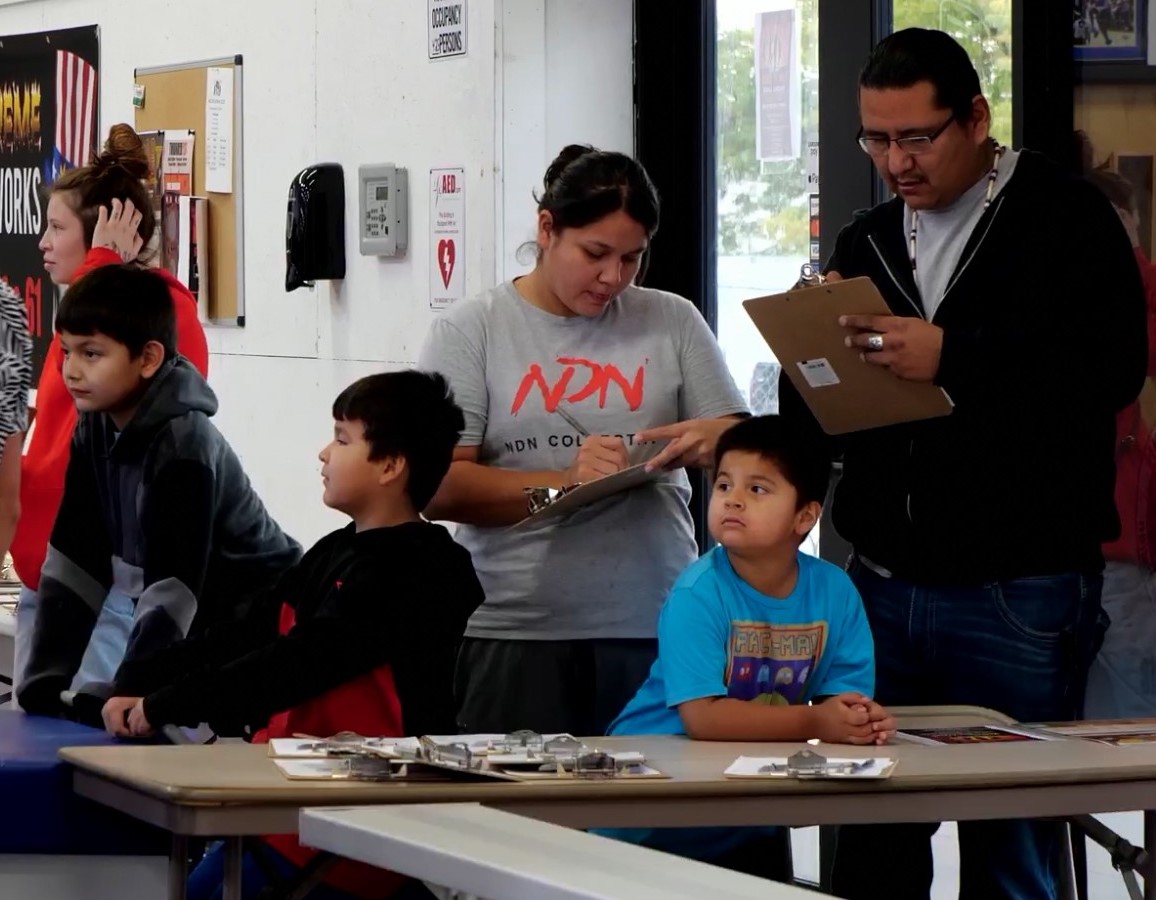

“If we start voting, we’re going to be respected,” said Chase Iron Eyes of the Lakota People’s Law Project, whose group held an Oceti Vote Fest in Rapid City on Oct. 22-23 featuring a basketball tournament and concert, with staffers on hand to help people with registration forms. “If we don’t vote, we don’t matter.”

These efforts come as Republican Gov. Kristi Noem seeks re-election Nov. 8 against Democratic challenger Jamie Smith, a race that a South Dakota State University poll conducted in late September and early October showed as within the margin of error.

It’s also a time of increased focus on voting rights and election security, partly influenced by former president Donald Trump’s refusal to concede the 2020 election despite no evidence of widespread electoral fraud. Heavily Democratic counties such as Oglala Lakota (home of the Pine Ridge reservation) and Todd (home to the Rosebud reservation) can loom large in close statewide elections and voting practices there have also been scrutinized by supporters of the Republican-dominated status quo.

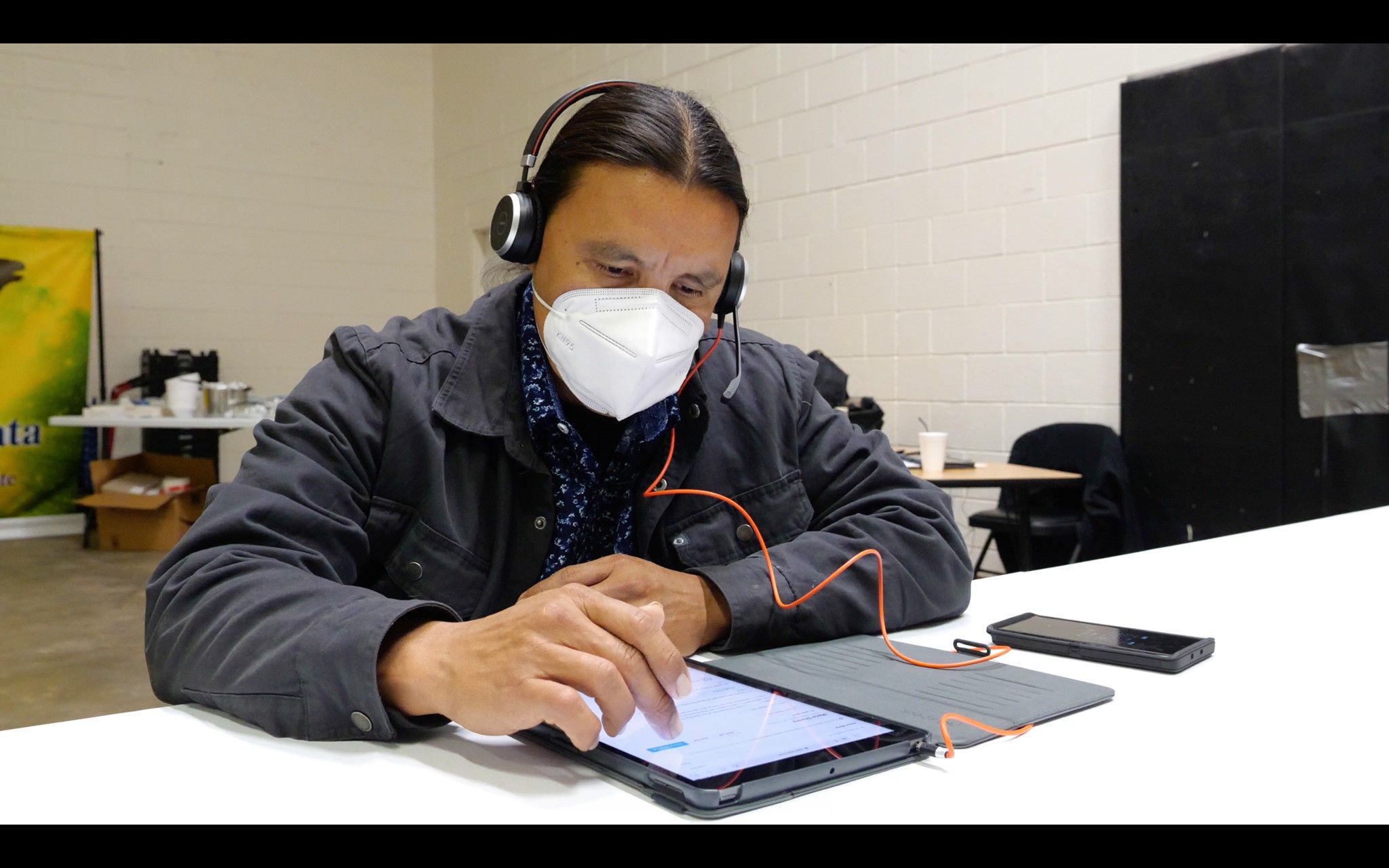

Chase Iron Eyes of the Lakota People's Law Project checks in at a voter outreach phone bank on the Standing Rock Indian Reservation in October 2020. (Photo: Courtesy Lakota People's Law Project)

Chase Iron Eyes of the Lakota People's Law Project checks in at a voter outreach phone bank on the Standing Rock Indian Reservation in October 2020. (Photo: Courtesy Lakota People's Law Project)

South Dakota Secretary of State Steve Barnett pointed to a tug-of-war between making it easy for eligible citizens to vote while ensuring that nobody tries to subvert the system through the absentee ballot or voter registration process.

Nationally, 34 percent of voting-age American Indians and Alaska Natives are not registered to vote, compared with 26.5 percent of non-Hispanic whites, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. Low turnout is also a concern: Oglala Lakota (41 percent) and Todd (55 percent) lagged well behind the statewide turnout of 74 percent for the 2020 general election.

Reasons for Indigenous non-participation in elections range from cultural and language barriers to socioeconomic realities and geographical challenges, such as long driving distances to the nearest polling site. For many reservation residents, the registration and voting process is complicated by not having a traditional street address, home mail delivery or broadband.

Barnett noted that there are several absentee voting satellite sites in reservation communities such as Eagle Butte, Wanblee and Mission, the result of legal battles between Native advocacy groups and past secretaries of state. Lawsuits have been filed accusing state officials of ignoring federal voting rights laws and in some cases pushing for more restrictive policies that disproportionately affect minority or low-income residents.

In May of 2022, a federal judge agreed with the Rosebud Sioux and Oglala Sioux tribes that South Dakota had violated portions of the National Voter Registration Act (NVRA), which was signed by President Bill Clinton in 1993 and took effect in 1995. The law requires state officials to provide voter registration information and guidance to eligible voters when they renew their driver’s license at the Department of Motor Vehicles or when receiving public assistance (such as food stamps or Medicaid) at the Department of Social Services and other state agencies.

In representing the tribes, the Native American Rights Fund produced data showing that the amount of voter registration applications processed through South Dakota public assistance agencies decreased by 57 percent from 2004 to 2018, from 7,000 applications down to 2,981. The lawsuit also accused Department of Public Safety officials of not properly transmitting voter registration forms to county auditors in some cases.

“It was not a priority, to say the least, and the extent to which it was not a priority suggests a level of voter suppression,” said Samantha Kelty, a Washington D.C.-based attorney with the Native American Rights Fund.

Judge Lawrence Piersol granted a summary judgment saying the tribes had “supported their claims of improper implementation of the NVRA by the Secretary of State, Department of Public Safety, and Department of Social Services,” adding that Barnett as the chief elections officer “contributed to these failings through inadequate training and oversight.”

As part of the settlement reached in September 2022, Barnett said his office designated Suzanne Wetz as state NVRA coordinator to oversee the training and oversight process, which includes public reporting of voter registration data. The state has also changed the wording on driver’s license applications so that the form requires a person to opt-out of the voter registration process, rather than requiring them to opt-in.

Barnett said he has had to remind legislators during session that state laws running counter to federal provisions put the state at risk of lawsuits such as the one brought by the Oglala and Rosebud tribes. Lyman County was ordered by a federal judge in August of 2022 to work with the Lower Brule Sioux Tribe to change the county commission election process, which used an at-large system that denied representation by diluting the vote of the county’s 38% Native population.

“We play a lot of defense during session, basically telling legislators, ‘Pass all the state laws you want, but make sure they comply (with the NVRA),’” said Barnett, who was defeated for the 2022 GOP nomination by Monae Johnson. “Our goal is to provide reasonable access and make it hard to cheat, but it’s tough to please everybody. It would be nice to take the politics out of it.”

That’s hard to do when the Native American vote has been instrumental in races such as Democrat Tim Johnson’s U.S. Senate win over then-Congressman John Thune in 2002, the result of registration drives and get-out-the-vote efforts in reservation counties.

Supporters of greater ballot access insist that giving all citizens an opportunity to engage in the democratic process is not a partisan endeavor.

“We don’t care how Native Americans vote, we just want them to be able to vote, and we work across the country to make that happen,” said Kelty. “Native Americans are not a monolith. Every tribe is different, and every individual is different.”

Jamie Smith has made several trips to Oglala Lakota County during his campaign, including an Oct. 11 reservation swing through Pine Ridge, Porcupine and Kyle with state legislators Red Dawn Foster and Peri Pourier.

Gov. Noem’s spokesperson, Ian Fury, didn’t respond to a request for information about Native outreach efforts made during her re-election campaign. In Noem’s 2018 race against Democrat Billie Sutton, she received just 214 votes (7%) in Oglala Lakota County, the lowest percentage for a major-party gubernatorial candidate in the county in at least 40 years.

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher