- Details

- By Jenna Kunze

OKLAHOMA CITY—LeEtta Osborne-Sampson, 59, can trace her Seminole ancestry back to the Civil War era, when her great-great-great-grandparents were counted in the federal Indian census that tribes still use today to determine Native American citizenship in Oklahoma. Her family has been considered members of the Seminole Tribe of Oklahoma ever since.

But because of her mixed African ancestry, Osborne-Sampson is marked as something else on her tribal ID: ‘FREEDMAN CITIZEN.’

‘0/0 INDIAN BLOOD’ the front of her Seminole Nation of Oklahoma card reads. On the back: ‘VOTING BENEFITS ONLY.’

“Call it what it is: To me it’s strictly racism,” said Osborne-Sampson, who grew up in Seminole County and has served on the tribe’s 28-member council for 11 years. In her tribe, she is one of roughly 3,000 enrolled “Freedmen,” descendants of enslaved black people once held by the five tribes that were relocated to Oklahoma on the Trail of Tears.

Want more Native News? Get the free daily newsletter today.

The 1907 census records, called the Dawes Commission Rolls, show there were 23,405 Freedmen in Oklahoma brought from the southeast—most as slaves—by the Five Civilized Tribes: Cherokee, Seminole, Muscogee (Creek), Chickasaw, and Choctaw. When the Civil War ended and slavery was abolished, each Indian Nation signed a treaty with the US government ceding certain lands, and also relinquishing the right to own slaves. In those treaties, each tribe agreed that Freedmen and their descendants “shall have and enjoy all the rights of Native citizens.”

In practice, that promise has looked a lot different.

‘Jim Crow moves’

Today, only the Cherokee Nation grants full and equal citizenship to its Freedmen as citizens in a historic and controversial move. As citizens, Freedmen are given access to tribal services such as health care, education, housing assistance, and federal dollars such as Covid-19 relief funding.

Freedmen belonging to the four other Oklahoma tribes—Seminole, Muscogee (Creek), Chickasaw and Choctaw—say their tribal nations are breaking the treaties they signed in 1866 by denying them equal rights.

“In the second column of our treaty, it does state that we are equal,” Osborne-Sampson said.

But when she sought a Covid-19 vaccination from her local Indian Health Services clinic in February, she was denied it based on her Freedmen status. Vaccines were for tribal members only, Osborne-Sampsom was told.

Though Seminole Freedmen are counted as tribal “citizens,” they are not considered “members” eligible for tribal services since the Seminole Nation —along with the rest of the Five Civilized Tribes in Oklahoma—changed their constitution’s language to limit eligibility to those with Native bloodlines, effectively stripping citizenship from all Freedmen.

“They say they did not recognize me—being a Freedman—to receive that (vaccination) shot,” Osborne-Sampson said. “They use a lot of play on words, and I call them Jim Crow moves, because they say that I'm a citizen and not a member. It just doesn't make sense.”

A fraught history

Citizenship for the Freedmen of the Five Civilized Tribes has long been a disputed topic. Each tribe tried to remove its Freedmen at one point or another, in some cases successfully.

Changes to the Muscogee (Creek) constitution in 1979, the Choctaw constitution in 1983, the Seminole constitution in 1999, the Chickasaw constitution in 2002 and the Cherokee constitution in 2007 mandated that citizens of each respective nation be tribal descendants “by blood.”

The amendments effectively expelled Freedmen from the tribes, a decision that was met with legal challenges by Freedmen from both the Cherokee and Seminole nations.

When Osborne-Sampson’s tribe tried to strip its Freedmen of citizenship in 1999, a group filed a federal lawsuit that resulted in the Department of the Interior upholding Freedmen’s rights to equitable tribal services, and asserted the Department’s authority in protecting treaty rights. The Seminole Nation has not lived up to the federal ruling by continuing to bar Osbone-Sampson and other Seminole Freedmen from all tribal services.

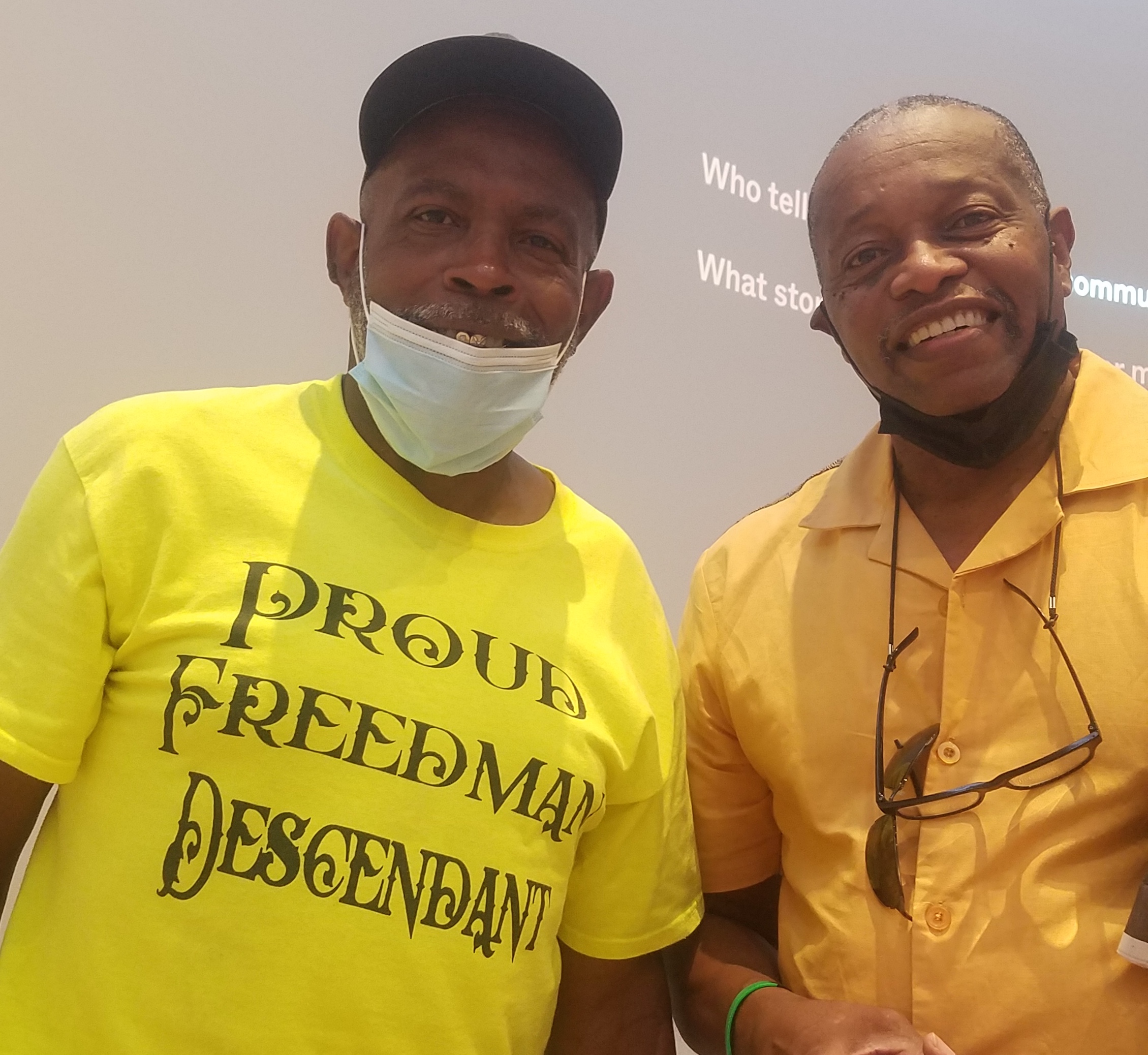

Muscogee (Creek) Freedman Ivory Vann (pictured left) was twice denied tribal citizenship despite generations of ancestors who were enrolled tribal members. (Photo/Ivory Vann)

Muscogee (Creek) Freedman Ivory Vann (pictured left) was twice denied tribal citizenship despite generations of ancestors who were enrolled tribal members. (Photo/Ivory Vann)

“Now I had to go outside of the tribe and go back to Washington and tell them how my people are suffering, because I was voted in,” Osborne-Sampson said. “With an injustice to this sheer enormous amount, you’ve got to understand that I have to do my due diligence for the people.”

In the three other Oklahoma tribes, Freedmen aren’t recognized at all.

Muscogee (Creek) Freedman Ivory Vann, also a Muscogee City Councilmember, was twice denied tribal citizenship in 2016, despite his father, grandfathers and generations before him being accepted as enrolled tribal members to the Nation.

In protest, he wears a T-shirt proclaiming his 'Proud Freedman Descendant' status to council meetings. On the back, he said, is the Creek’s Treaty of 1866.

“I think they’re very selfish...to not recognize the Freedmen,” Vann said. “We have missed out on so much.”

A matter of identity

Marilyn Vann (no relation to Ivory Vann), a Cherokee Freedmen with some mixed African ancestry, is an enrolled tribal member and founder of the non-profit group Descendants of Freedmen of the Five Civilized Tribes. She knew she was a Cherokee from a young age, but it wasn’t until 2000 that she collected her ancestral information to apply, Vann said.

“I registered thinking that this was going to be easy,” she said. “Until I was denied citizenship, I had never heard the word Freedmen.

“I knew that my father was a registered member of the tribe. And so I just presumed that, once I found the roll number ... that I could simply prepare this application, and I would get my own tribal membership card. I mean, why should it be difficult?”

Cherokee Freedman Marilyn Vann (pictured right) has testified before Congress and said she has spent more than $100,000 of her own money to advocate and publicize Freedmen rights. (Photo/Marilyn Vann)Vann got her citizenship in 2006, after bringing a federal lawsuit against the Department of the Interior. But her birthright was called into question once again the following year when tribal members voted to add “by blood” to the tribe’s constitution.

Cherokee Freedman Marilyn Vann (pictured right) has testified before Congress and said she has spent more than $100,000 of her own money to advocate and publicize Freedmen rights. (Photo/Marilyn Vann)Vann got her citizenship in 2006, after bringing a federal lawsuit against the Department of the Interior. But her birthright was called into question once again the following year when tribal members voted to add “by blood” to the tribe’s constitution.

It wasn’t until a federal court in 2017 ruled that the Cherokee Nation is bound by its treaty to give Freedmen citizenship that Vann’s position—along with about 8,500 other Cherokee Freedmen–was secured.

“Our people endured the Trail of Tears,” she said. “Now, to have tribal leaders say, ‘go away and just be this black person. Forget about your identity. Forget about your blood lines. Just go away. We have power. We control casinos, we can do what we want.’ How does that make our people feel? it's not right. It's not legal.”

"Treaties ought to mean something," said. Cherokee Nation Chief Hoskin.

"Treaties ought to mean something," said. Cherokee Nation Chief Hoskin.

Cherokee Nation tribal Chief Chuck Hoskin agreed.

“The issue of Freedmen citizenship was considered in resolve by our ancestors 155 years ago, when we signed the Treaty of 1866,” Hoskin told Native News Online. “Treaties ought to mean something. There's only one way to keep our promise with respect to Freedmen citizenship, and that is full equality.”

The Cherokee tribe began enrolling its Freedmen in 2017, following the federal court case.

In May 2021, the Department of the Interior Secretary Deb Haaland approved the Cherokee Nation’s amended constitution that guarantees full citizenship rights to “original enrollees or descendants of original enrollees listed on the Dawes Commission Rolls.”

Tribal response

After decades of prejudice, the moves by the Cherokee Nation, the courts and the DOI have set off a chain of events.

Department of the Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, in approving the Cherokee constitution in May, encouraged all Oklahoma tribes “to take similar steps to meet their moral and legal obligations to the Freedmen."

In response, chiefs from the Muscogee (Creek) Nation and Choctaw Nation expressed a willingness towards “conversations” on citizenship eligibility.

Donate today to help us share Native Voices, Native Perspectives, and Native News.

David Hill, the chief of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation, on April 29 wrote to the tribe’s National Council speaker, Randall Hicks, encouraging him to “lead a conversation” on citizenship eligibility, beginning with town-hall style forums for tribal citizens to share their thoughts.

“This deeply personal and highly emotional issue goes to the heart of identity for both Creek citizens and the descendants of Freedmen,” Hill wrote. “As a nation committed to truth and justice it is important that we reflect upon this issue with an open heart to seek to understand what is right and equitable.”

More than three months later, Muscogee (Creek) Nation spokesperson Jason Salsman told Native News Online that no constitutional amendment has been proposed by a tribal citizen.

“If (tribal citizens) want to do that, there is a process in our Constitution to bring forth an amendment to change our citizenship standard,” he said. “But the citizens have to do that, it's not a decision of the chief.”

Salsman called the topic “very polarizing” and said that when the chief put out the letter, there were people that wanted to impeach him.

Salsman characterized some of the major arguments against Freedmen citizenship as a fearfulness of what might happen to the tribe if blood lineage isn’t a standard, and an argument from a group that claims their specific ancestors never held slaves.

“The citizens that are for it, say, ‘This is the right thing to do. We need to honor the Treaty of 1866. It says it in there, and it's the right thing to do,” Salsman said. “The folks that are against it say, ‘That may be what it says in the Treaty of 1866, but our people never owned slaves. And we would like to see blood lineage as the standard for citizenship.’”

Similarly, in an open letter published May 27, Choctaw Nation Chief Gary Batton announced an initiative to consider tribal membership for Choctaw Freedmen.

“The story of Choctaw Freedmen deserves our attention and thoughtful consideration within the framework of tribal self-governance,” Batton wrote. “Today, we reach out to the Choctaw Freedmen. We see you. We hear you. We look forward to meaningful conversation regarding our shared past.”

A spokesperson from the Choctaw Nation said the chief had no further comment.

Financial consequences

Last month, U.S. Rep. Maxine Waters (D-CA) submitted a draft bill for the reauthorization of the Native American Housing Assistance and Self Determination Act (NAHASDA) that proposed withholding millions in annual federal housing funds from Oklahoma tribes that fail to comply with their treaty obligations to Freedmen.

U.S. Rep Maxine Waters (D-CA)“While access to housing sits at the heart of many racial and economic injustices across the country, including, among Native American communities … We also know that a key determinant of housing access on reservation is tribal citizenship, which is one of the barriers faced by descendants of black Native American Freedmen today,” Waters said in a subcommittee meeting last month.

U.S. Rep Maxine Waters (D-CA)“While access to housing sits at the heart of many racial and economic injustices across the country, including, among Native American communities … We also know that a key determinant of housing access on reservation is tribal citizenship, which is one of the barriers faced by descendants of black Native American Freedmen today,” Waters said in a subcommittee meeting last month.

“For one minority group to discriminate against a minority group, as the chair of this committee, I don’t intend for it to stand,” said Waters, who is also also a senior member of the Congressional Black Caucus.

Cherokee Freedman Marilyn Vann also testified, asking the House Financial Services Committee to include treaty obligations in the final language of NAHASDA. She pointed to data showing a disparity between Native Americans and African Americans in the state.

A Tulsa-based think tank, the nonprofit Oklahoma Policy Institute, published a report in 2010 that showed Native Americans in the state earned $11,216 below the median income for the state. By comparison, the state’s African Americans earned even less at $18,231 below the state median income. While about 63 percent of Native Americans owned homes, less than half of Oklahoma’s African Americans could say the same.

Vann told Native News Online that these figures are a direct result of federal, state, and tribal government policies discriminating against African Americans, including descendants of tribal Freedmen. Now, Freedmen like herself have to pay thousands of dollars out of pocket for legal fees in order to secure their birthrights. Personally, Vann said she spent over $100,000 of her own money to advocate and publicize Freedmen rights.

Now, Vann is teaming up with Osborne-Sampson “to get this resolved” for the Seminole Freedmen, and potentially others, beginning with raising funds for legal recourse.

“People can say, ‘Well, why aren't you doing something?’ Or “What are you doing?’ Well, you know, again, all of that takes time,” Vann said. “It takes effort. It takes money. And so the wheels of justice (turn slowly).”

More Stories Like This

Navajo Committee Advances $84M Transportation Improvement PlanNCAI Passes Two Emergency Resolutions on Immigration Enforcement Activities

Chickasaw Lighthorse Police Officer named Indian Country Law Enforcement Officer of the Year

Indian Gaming Association Rallies Broad Coalition Against Sports Event Contracts It Calls Illegal Threat to Tribal Sovereignty

Navajo Resources and Development Committee Issues Notice on Livestock Inspection Requirements

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher