- Details

- By Jenna Kunze

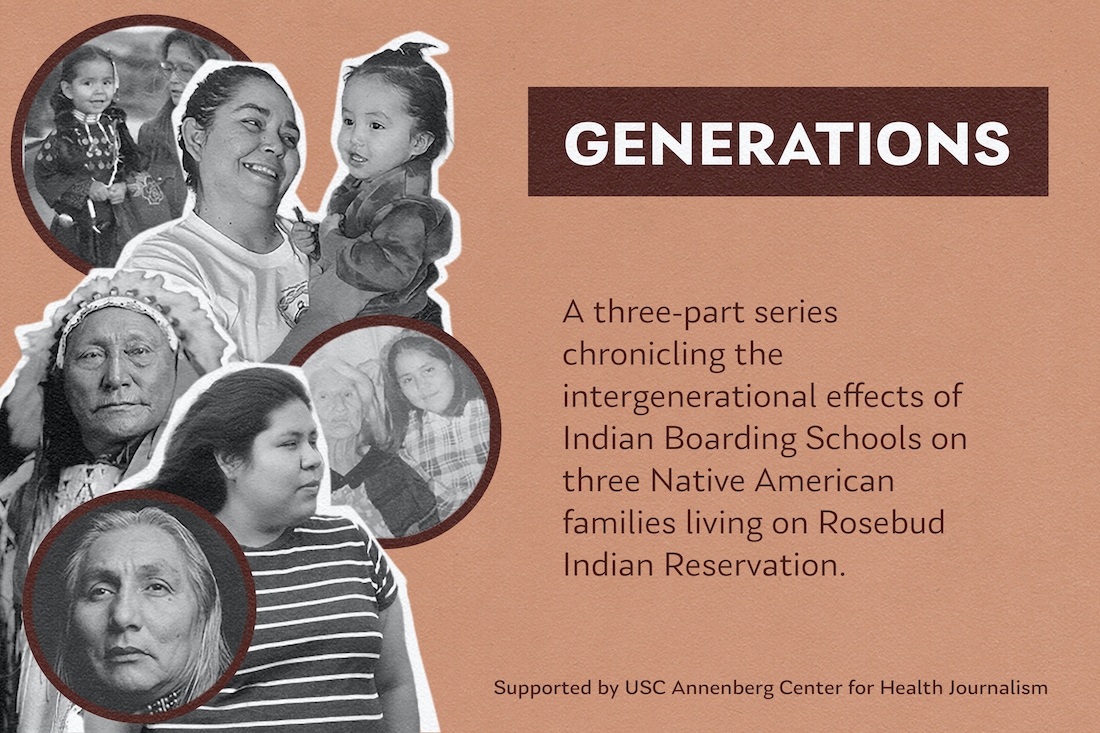

A special three-part series following the intergenerational effects that the United States government’s century-and-a-half practice of placing Indian children in boarding schools has had on three families living on Rosebud Indian Reservation in South Dakota. This story was produced as a project for the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism's 2021 Data Fellowship.

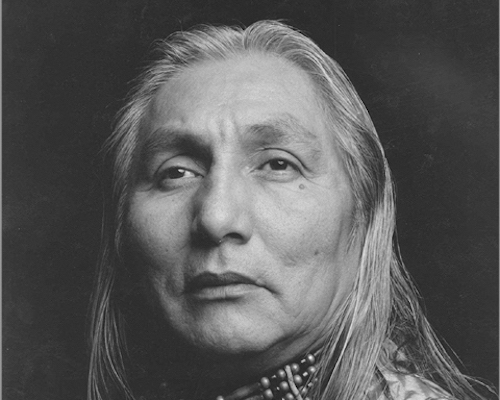

Part One: Survivors

Now in his 70s, Duane Hollow Horn Bear was part of the last generation to attend an institution designed by the U.S. government to strip Natives of their culture and lands, but he’s not the last or the only one to live with the effects caused by Indian boarding schools.

He entered St. Francis Mission school when he was eight years old and stayed until he graduated, at 20. The old school buildings have since been demolished and rebuilt. But the memories remain.

Perhaps the largest scar that boarding school left on Hollow Horn Bear and the preceding generations came from its separating Native kids from their families, languages, cultures, and traditions for nine months of each year of their entire adolescence. Growing up mostly without his parents and grandparents, he said he didn’t know how to raise children, and eventually neglected his own.

Read the story.

Part Two: First Generation Descendants

Part Two: First Generation Descendants

In scrolling black ink, LeToy “Toy” Lunderman illustrates intergenerational trauma like this: three big circles represent three generations, the first circle nearly empty but for a sliver of solid—representing all that was taken from survivors of boarding school—and the subsequent circles gradually filling with solid until the last circle is whole again.

She’s the middle circle, the conduit between hardship and healing, among the generation of children born in the mid ‘70s who grew up in the years immediately after the federal government abandoned its Indian Boarding School policy.

But it would take her a while to recognize how deeply she’s been impacted by a school system she didn’t directly experience, though she was educated in the same buildings where many in the generations before her experienced abuse: Saint Francis Indian School, formerly Saint Francis Mission, on the Rosebud Indian Reservation in South Dakota.

Read the story.

Part Three: Young Adults Today

Part Three: Young Adults Today

They were just kids when they learned about the Native children, their ancestors, who never came home from Indian boarding school more than a 100 years before.

Seven years ago, a group of Rosebud Sicangu Youth Council members were traveling back from a conference in Washington when the tribal leaders chaperoning them suggested that the group make a side trip to see a bit of their history: the site of the former Carlisle Indian Industrial School, in Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

Now, young adults on the Rosebud Indian Reservation continue to lead the efforts to bring home lost ancestors buried at the former boarding schools—all while coming to terms with the ways in which their grandparents’ and great-grandparents’ experiences at those schools affect their lives today.

Read the Story.

More Stories Like This

50 Years of Self-Determination: How a Landmark Act Empowered Tribal Sovereignty and Transformed Federal-Tribal RelationsMuscogee Nation and City of Tulsa Reach Agreement on Criminal Jurisdiction and Public Safety Collaboration

Panel on Ethical Tribal Engagement at OU Highlights Healing, Research and Sovereignty

Groundbreaking Held for Western Navajo Pipeline Phase I – LeChee Water System Improvement Project

Navajo Citizens Voice Mixed Reactions to Trump’s Coal Executive Order at Public Hearing

Help us tell the stories that could save Native languages and food traditions

At a critical moment for Indian Country, Native News Online is embarking on our most ambitious reporting project yet: "Cultivating Culture," a three-year investigation into two forces shaping Native community survival—food sovereignty and language revitalization.

The devastating impact of COVID-19 accelerated the loss of Native elders and with them, irreplaceable cultural knowledge. Yet across tribal communities, innovative leaders are fighting back, reclaiming traditional food systems and breathing new life into Native languages. These aren't just cultural preservation efforts—they're powerful pathways to community health, healing, and resilience.

Our dedicated reporting team will spend three years documenting these stories through on-the-ground reporting in 18 tribal communities, producing over 200 in-depth stories, 18 podcast episodes, and multimedia content that amplifies Indigenous voices. We'll show policymakers, funders, and allies how cultural restoration directly impacts physical and mental wellness while celebrating successful models of sovereignty and self-determination.

This isn't corporate media parachuting into Indian Country for a quick story. This is sustained, relationship-based journalism by Native reporters who understand these communities. It's "Warrior Journalism"—fearless reporting that serves the 5.5 million readers who depend on us for news that mainstream media often ignores.

We need your help right now. While we've secured partial funding, we're still $450,000 short of our three-year budget. Our immediate goal is $25,000 this month to keep this critical work moving forward—funding reporter salaries, travel to remote communities, photography, and the deep reporting these stories deserve.

Every dollar directly supports Indigenous journalists telling Indigenous stories. Whether it's $5 or $50, your contribution ensures these vital narratives of resilience, innovation, and hope don't disappear into silence.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Native languages are being lost at an alarming rate. Food insecurity plagues many tribal communities. But solutions are emerging, and these stories need to be told.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Native languages are being lost at an alarming rate. Food insecurity plagues many tribal communities. But solutions are emerging, and these stories need to be told.

Support independent Native journalism. Fund the stories that matter.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher