- Details

- By Andrew Kennard, The Times-Delphic

TOLEDO, Iowa — Marian Wanatee said her mother, Adeline, talked little about her experiences at the Flandreau Indian School in South Dakota and the Haskell Institute in Lawrence, Kansas.

[This story was originally published in The Times Delphic, the student newspaper of Drake University. Used with permission.]

Wanatee is a citizen of the Meskwaki Nation, a sovereign government of Indigenous Meskwaki people based in a settlement in Tama County, Iowa. Her mother Adeline attended a federal boarding school that was part of a system created in the late 1800s to assimilate Indigneous peoples in the United States.

During that era, Native children were taken from their homes, often forcibly, and sent to Indian boarding schools as part of a government effort to strip them of their cultural identity and assimilate them into white Euro-American Christian culture.

“To me, you know, it was appalling [that] they would be sent off like that from their tribe,” Wanatee said.

Indian boarding school students’ diets lacked “quantity, quality and variety,” according to a 1928 report to the U.S. Secretary of the Interior. Dorms were overcrowded, disease was prevalent and students received substandard education and medical care, according to the Meriam Report. The report also said that students above fourth grade spent half of their day maintaining their schools.

Like many other Indigenous students of the boarding schools, Adeline Wanatee was forbidden from speaking her native language, according to a 1978 book she contributed to as well as the book Boarding School Seasons by Minnesota University professor Brenda Child.

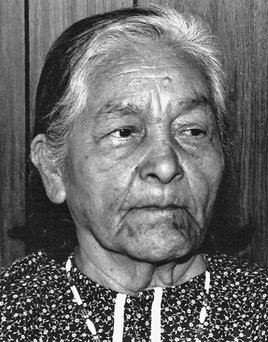

Adeline Wanatee (Iowa Dept. Human Rights)“And, where the Indian people are involved, the Anglo-controlled schools, the Bureau of Indian Affairs schools and the missionary and public schools have openly and consistently sought to destroy the native tribal cultures and tried to impose the Anglo culture,” Adeline Wanatee wrote for the book The Worlds Between Two Rivers.

Adeline Wanatee (Iowa Dept. Human Rights)“And, where the Indian people are involved, the Anglo-controlled schools, the Bureau of Indian Affairs schools and the missionary and public schools have openly and consistently sought to destroy the native tribal cultures and tried to impose the Anglo culture,” Adeline Wanatee wrote for the book The Worlds Between Two Rivers.

Adeline Wanatee went on to advocate for Indigenous rights at the state and national level, and she became the first woman elected to the Meskwaki Tribal Council and the first American Indian inductee of the Iowa Women’s Hall of Fame, according to the University of Iowa Press.

‘These painful experiences that still linger’

On May 27, the Tk'emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation announced that a ground penetrating radar scan at the site of the Kamloops Indian Residential School in British Columbia, Canada had revealed the remains of 215 students who had never returned to their families. Native News Online reported that over the next two months, other First Nations announced the detection of an estimated total of 1,093 more unmarked graves at Indian residential schools across Canada.

“The tragedy at Kamloops is a painful reminder of the human rights violations that occurred at hundreds of Indian boarding schools run by the U.S. government and churches across the United States,” the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition (NABS) said in a June 7 press release.

In 1920, Canada’s Indian Act made it mandatory for Indigenous students to attend residential schools, according to the Indigenous Foundations project from the University of British Columbia. After an extensive investigation, Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission concluded in 2015 that the country’s residential school policy from 1867 to the late 1990s had suppressed Indigenous languages and cultures, “institutionalized” child neglect and created educational goals that “usually reflected a low regard” for the intelligence of the students.

“The door had been opened early to an appalling level of physical and sexual abuse of students, and it remained open throughout the existence of the system,” the commission’s final report says.

Levi Rickert, founder of the digital publication Native News Online, said he thinks there has been a reckoning in response to the news from Kamloops. Rickert said that a new awareness of racial issues that followed George Floyd’s murder has contributed to the renewed focus on the Indian boarding school systems.

Rickert added that coming to terms with these experiences has been traumatic for Indigenous communities.

“All of the sudden, people are saying, it may be more healthy to talk about these situations,” Rickert said. “If we’re going to get to long-term healing, we have to bring it out into the open and start discussing some of these painful experiences that still linger.”

‘A necessary first step’

On June 22, U.S. Interior Secretary Deb Haaland announced the opening of a federal investigation into former U.S. Indian boarding schools.

Haaland said the investigation will identify boarding school facilities and known or potential burial sites near the schools, as well as the identities and tribal affiliations of students taken there. On Sept. 30, the Interior Department announced that it had invited tribal governments, Alaska Native corporations, and Native Hawaiian organizations to provide feedback for the investigation’s final report and help the department protect burial sites and other sensitive information.

“Beginning with the Indian Civilization Act of 1819, the United States enacted laws and implemented policies establishing and supporting Indian boarding schools across the nation,” the Interior Department said in a June 22 press release. “The purpose of Indian boarding schools was to culturally assimilate Indigenous children by forcibly relocating them from their families and communities to distant residential facilities where their American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian identities, languages, and beliefs were to be forcibly suppressed. For over 150 years, hundreds of thousands of Indigenous children were taken from their communities.”

On Sept. 30, a bill that would create a Truth and Healing Commission on Indian Boarding School Policies in the U.S was reintroduced in Congress, according to a press release from Senator Elizabeth Warren’s office. The proposed commission would investigate and document the experiences, impact, and ongoing effects of the federal boarding school system.

“The work of a commission will be a necessary first step in the healing journeys for many of the generations of Native people who have experienced loss due to Indian boarding schools,” NABS CEO Diindiisi McCleave said in a Sept. 30 press release.

The Indian Training School at Toledo

According to NABS, 367 boarding schools operated in the United States between 1869 and the 1960s. The Indian Training School at Toledo was established in the late 1890s about four or five miles from the Meskwaki settlement, according to Judge John R. Caldwell’s 1910 history of Tama County.

Following various small-scale attempts to establish schooling for the Meskwaki between 1875 and 1898, demand for assimilation grew strong near the turn of the century, according to MacBurnie Allinson’s 1974 dissertation on “Education and the Mesquakie.”

In 1895, federal Indian agent Horace Rebok organized an “Indian Rights Association,” which held that “the problem of [the Mesquakies’] civilization lies in the line of christianization and education,” according to Rebok, Caldwell and E.C. Ebersole’s report about the association and the Indian Training School in Toledo Boarding School.

“We have to break the power and influence of the chiefs and medicine men before there will be any marked progress in the tribe,” Rebok wrote in 1895, according to the report.

In a meeting with Chief Pushetonequa of the Meskwaki, Rebok attempted to convince the chief that having Meskwaki children put in the Indian Training School in Toledo Boarding School would be to their benefit, according to the report.

“My friend, the Musquakies have always been friends to the white people, but they will not accept your school,” Pushetonequa replied, according to Rebok’s report. “You may come and kill us, but we will not give you our children. I will say no more.”

Despite this, the chief was eventually persuaded to accept the school in open council in late 1898, and by June 30, 1899, total enrollment had climbed to 50 students, according to Rebok’s report.

According to Johnathan Buffalo, the Meskwaki Nation’s current historic preservation director, the children were required to go to the school.

To get more children to attend the school, Rebok went to the Tama district court, according to Caldwell. The court transferred the guardianship of 20 Mesquakie children to, in most instances, federal Indian agent W.G. Malin, according to Rebok’s report and Caldwell. Rebok’s report says that these children were neglected orphans, although Buffalo said the government did not understand the tribe’s family structure.

“Well, when you live in a tribe, you always have mother and father figures,” Buffalo explains. “They may not be your biological parents, but you always have grandma, grandpa that these kids were living with.”

One of Malin’s charges, a Meskwaki girl named Le-lah-puc-ka-chee, left the school without permission and was brought back, according to Caldwell. On Dec. 29, 1899, a judge ruled that Le-lah-puc-ka-chee could not be compelled to attend the school, according to Buffalo and Caldwell.

“The effect of this decision was disastrous to the school,” Caldwell wrote in his history of Tama County. “The elder Indians had been intensely hostile to it… When the news reached the Indians of the decision above quoted, the school was practically depopulated in a day and very few Mesquakie children have been in attendance since that time.”

Buffalo said that Native Americans from other tribes were then brought in to fill the Indian Training School in Toledo Boarding School. He said that after the school closed in 1911, the government started sending Meskwaki children to boarding schools in other states—including Adeline Wanatee.

“We won the battle, but in a way, we lost the war,” Buffalo said. “Because our kids ended up being taken far away.”

Andrew Kennard, a second-year student at Drake University, worked as a summer reporting intern at Native News Online in 2021. He is the news editor for The Times-Delphic, the student newspaper at Drake.

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher