- Details

- By Stephen Carr Hampton

Guest Opinion. Eleven years before the Declaration of Independence, when Cherokee peace chief Attakullakulla met with British diplomats, his first question was, “Where are your women?” Because they had none with them, Attakullakulla assumed the British were not serious about negotiations.

Among the Cherokee entourage was likely my eight-times great grandmother, Nanye’hi, Nancy Ward. As a Beloved Woman of the Wolf Clan of the Cherokee, she led the women’s council, granted clemency to prisoners of war, helped negotiate treaties, and advised war and peace chiefs on strategies to protect Cherokee towns, fields, and water sources from the ravages of war. One of her letters to the male council sits today in the National Archives.

Her role was not unusual. Though cultures and societies varied across Turtle Island, political structures often employed a gender-based balance of powers. In simplified terms, most leaders were men, but only women could vote. Clan matriarchs selected chiefs and leaders and could remove them from office at any time. Testosterone was never allowed free reign.

The women’s standards were strict. A version of the Haudenosaunee criteria for leaders reads: “The thickness of their skin shall be seven spans -- which is to say that they shall be proof against anger, offensive actions and criticism. Their hearts shall be full of peace and good will and their minds filled with a yearning for the welfare of the people of the Confederacy. With endless patience they shall carry out their duty and their firmness shall be tempered with a tenderness for their people. Neither anger nor fury shall find lodgment in their minds and all their words and actions shall be marked by calm deliberation.”

This had an influence on male leaders, who were often noted for their generosity. A relative of the great Shawnee leader, Tecumseh, said that he “was remarkable for hospitality and generosity. His house was always supplied with the best provisions, and all persons were welcome and received with attention. He was particularly attentive to the aged and infirm, attending personally to the comfort of their houses when winter approached, presenting them with skins for moccasins and clothing…. He made it his particular business to search out objects of charity and extend the hand of relief.”

Many tribes had matrilineal societies; some still do. Rights and possessions were passed down through the mother’s line. Traditionally, upon marriage the groom moved into the family compound of the bride. One British fur trader warned his friends about marrying in, because “the women Rules the Rostt and weres the brichess.” European women, meanwhile, lived in near servitude.

The socio-political power of Indigenous women was – and still is – a reflection of their prominence in Native cosmology. Female goddesses and spiritual beings abound, often with the greatest significance. The concept of “Mother Earth,” a distant echo in European cultures, remains foundational in Native circles, where it has political significance. Among the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois), Sky Woman helped create the terra firma we stand on.

These stories communicate to Native children that women are not just equal, but have unique and critical roles in the functioning of our societies. This may be surprising to white settlers, who mostly interacted with war chiefs, the male-facing side of Native governance. They never saw the women that shepherded our people across countless generations.

Even in our modern history, prominent Native women are everywhere. The activism of Elizabeth Peratrovich (Tlingit) led to the Alaska Anti-Discrimination Act of 1945, the first such law in the US. In the 1950s, Vyola Olinger (Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians) led the first all-women tribal council, successfully lobbying Congress for the right to develop and manage their portions of Palm Springs. LaDonna Harris (Comanche) was a prominent figure in Washington, DC in the 1960s, teaching Indian 101 to members of Congress for 30 years. In the 1970s, Ada Deer (Menominee) led the fight against tribal “termination” and the first re-recognition of a terminated tribe. Around the same time, Maria Pearson (Yankton Dakota), Clara Spotted Elk (Northern Cheyenne), and Rosemary Cambra (Muwekma Ohlone) were catalysts in the creation of the Native American Graves and Repatriation Act. In the 1980s, Wilma Mankiller (Cherokee) spearheaded model economic development and the provision of healthcare and education on the reservation she headed. In the 1990s, the mathematical calculations and activism of Eloise Cobell (Blackfeet) led to a $3.4 billion settlement with the US government for unpaid royalties from reservation land.

These are not cherry-picked examples, exceptions to a rule of male-dominated leadership. Any list of Native leaders today would include Winona LaDuke (Ojibwe), Suzan Harjo (Hodulgee Muscogee/Southern Cheyenne), Rebecca Nagle (Cherokee), Fawn Sharp (Quinault), and Deb Haaland (Laguna Pueblo), the current Secretary of the Interior.

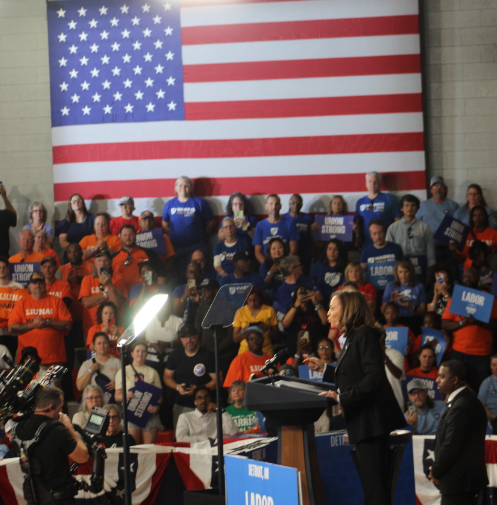

Forty-six presidents in, the US is long overdue for a woman leader, long ready to leave the Puritan servitude of women behind. Indigenous people have always been ready. Oral history tells us that Buffalo Calf Road Woman (Northern Cheyenne) played a role in killing Yellow-hair Custer, knocking him off his horse.

Perhaps now another woman will knock another Yellow-hair off his horse.

Stephen Carr Hampton is an enrolled citizen of Cherokee Nation. He lives in Port Townsend, Washington, where he is an active member of the Cherokee Community of Puget Sound. He is the author of the Memories of the People blog, dedicated to un-erasing history.

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher