- Details

- By Jenna Kunze

The U.S. Supreme Court set precedent for tribes to have jurisdiction over waste cleanup on land within a reservation in a historical move on Tuesday.

On Jan. 11, the high court declined to see a case that has been in limbo for over a decade, effectively upholding a lower court’s ruling on the regulatory authority for over 22 million tons of hazardous waste stored at a former phosphorus production plant on the Fort Hall Indian Reservation in Southeast Idaho.

The chemical manufacturing company who operated the plant for more than 50 years before abandoning it in 2002, FMC Corporation, will now be responsible for paying the Shoshone-Bannock Tribes who occupy the surrounding area $1.5 million to store hazardous waste materials.

Related: U.S. Supreme Court Rules in Favor of Shoshone-Bannock Tribe

According to the tribes’ general council, William Bacon, it’s a big deal that the courts gave the tribes regulatory jurisdiction over a polluter within a reservation. It represents a turning point in tribal nations' relations with industrial corporations polluting Native land, and then leaving without clean up or consequence.

“Tribes need to sit down at the table if they’ve got a polluter within their reservation and try to strike deals with them,” Bacon advised. “Leaving it as they found it, that type of deal would be the preference, because then you have consent. Tribes need to adopt environmental regulations that are not prohibitively strict but can be enforced.”

For companies that aren’t willing to agree to environmental regulations with a tribal ahead of time, Bacon said the only recourse a tribe has is litigation.

“If they won’t agree in writing to a fee or jurisdiction of the tribes, the only recourse is to go to court and say that their activity threatens the existence of the tribe,” he said. “It’s a pretty tall bar.”

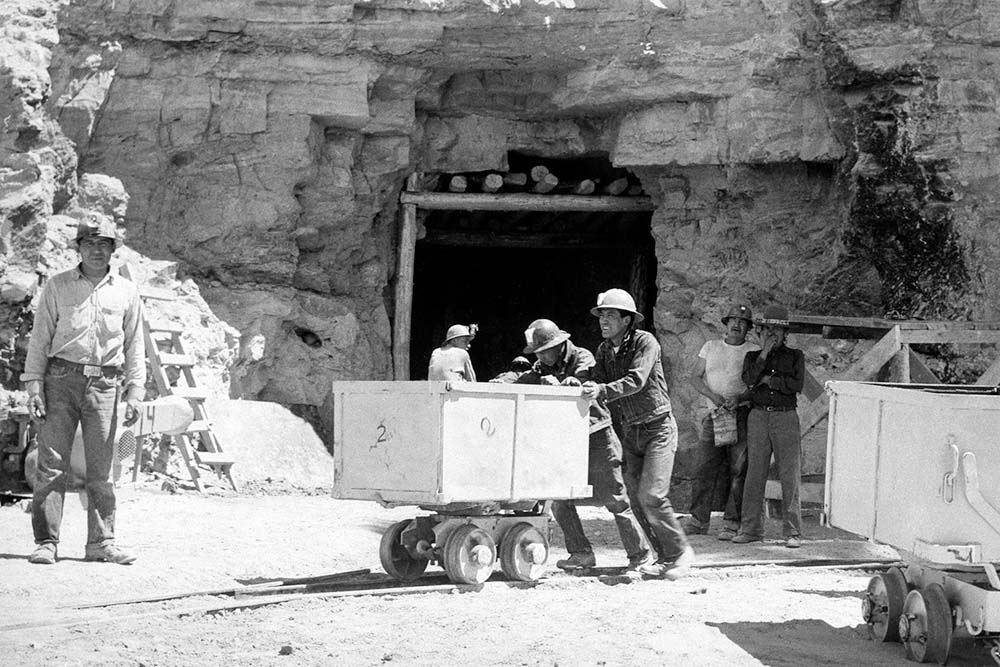

Navajo miners work at the Kerr-McGee uranium mine at Cove, Ariz., on May 7, 1953.

Navajo miners work at the Kerr-McGee uranium mine at Cove, Ariz., on May 7, 1953.

But this is just one example. Here are four more times a company has polluted on tribal lands and then skipped town, illustrating a widespread problem in Indian Country:

Sac and Fox Nation Tribes and Tenneco Oil

In 1997, the government filed a suit against Tenneco Oil, alleging that the company’s oil recovery process known as waterflooding polluted the groundwater and sole source of drinking water supply for the Sac and Fox Nation Tribes in Oklahoma. Tenneco settled the case, agreeing to construct water wells and restore bits of land where oil and gas production had destroyed vegetation.

Abandoned uranium mines on the Navajo Nation

From 1944 to 1986, nearly 30 million tons of uranium ore was extracted on or near the Navajo Nation, sold exclusively to the federal government to make atomic weapons. Today, there are more than 500 abandoned mines left on the land. One study found that cancer rates doubled in the Navajo Nation from the 1970s to 1990s as a result.

In 2017, two of the mining companies in partnership with the U.S. government agreed to foot the bill for a $600 million clean up project for 94 abandoned uranium mines.

Nez Perce Tribe fights back

In 2019, the Nez Perce Tribe in Idaho filed a lawsuit against Canadian mining company, Midas Gold, ordering the company to clean up an abandoned mine they say is polluting their hunting and fishing grounds.

Though no mining has taken place since Midas Gold purchased the abandoned gold pits over a decade ago, the tribe holds that the Canadian company is responsible under the Clean Water Act for preventing the discharge of water polluted with arsenic, cyanide and mercury, among other heavy metals, into salmon rearing streams tribal members rely on.

The U.S. Department of Justice urged a federal court in Boise, Idaho to throw out the case, but a federal judge on Jan. 10 refused.

Toxic pollutants in Navajo rivers

This week, mining company Sunnyside Gold Corp. agreed to pay the Navajo Nation and the state of New Mexico more than $20 million for a 2015 spill of toxic wastewater in southwest Colorado that poisoned rivers in three Western states.

Sunnyside Gold Corp. will pay the tribe $10 million for toxic water introduced to more than 200 miles of river on tribal land. The company will pay the state an additional $11 million for lost tax revenue, environmental clean up cost and injuries to the state’s natural resources.

"We pledged to hold those who caused or contributed to the blowout responsible, and this settlement is just the beginning,” Navajo Nation President Jonathan Nez said in a statement. "It is time that the United States fulfills its promise to the Navajo Nation and provides the relief needed for the suffering it has caused the Navajo Nation and its people."

The tribe has additional claims against the Environmental Protection Agency addressing the clean up. About 300 individual tribal members have also filed separate claims regarding the impact of the pollution.

***

As for the Shoshone-Bannock Tribes, general council Bacon said their recent jurisdiction victory isn’t the end of the litigation.

While the FMC Corporation will pay the tribes money to store hazardous waste materials, the Environmental Protection Agency is responsible for remediation of the toxic waste, though the tribes have a right to provide input. Bacon said it’s the tribes’ wish to remove the waste stored in 23 Olympic-sized ponds currently covered with dirt, while the EPA plans to cover it in perpetuity.

“Their remedy is cover-up, not cleanup,” Bacon said of the federal agency. “So I would anticipate in the not-too-distant future, we will be filing litigation again. We would sue the EPA over their choice of remedy.”

More Stories Like This

Native News Weekly (August 25, 2024): D.C. BriefsUS Presidents in Their Own Words Concerning American Indians

Senate Committee on Indian Affairs Passes 12 Bills to Strengthen Tribal Communities

Deb Haaland Tours CNM Workforce Facilities, Highlights Trade Job Opportunities

Federal Court Dismisses Challenge to NY Indigenous Mascot Ban

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher