- Details

- By Tamara Ikenberg

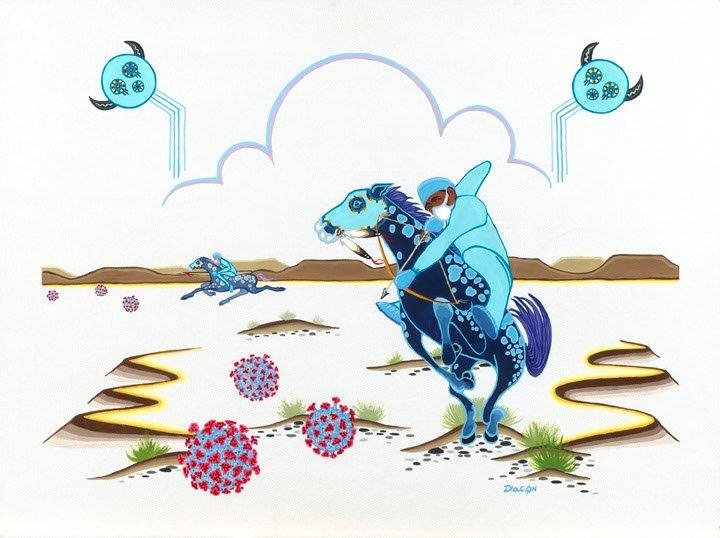

TULSA, Okla. — A masked hunter atop a masked horse slings arrows at the coronavirus in Mvskoke artist Johnnie Diacon’s flat-style painting “Tribute to the Healthcare Warriors in Indian Country During COVID-19, 2020.”

The painting was one of 80 submissions from all over the world selected for June and July’s “Quarantine” online art show presented by Tulsa Community College’s McKeon Center for  Mvskoke painter Johnnie Diacon specializes in the flat style of Indian art. (Johnnie Diacon)Creativity.

Mvskoke painter Johnnie Diacon specializes in the flat style of Indian art. (Johnnie Diacon)Creativity.

"Healthcare workers are kind of like warriors and I wanted to do a tribute painting in that old flat style, and I drew inspiration from the Navajo artist, Quincy Tahoma, who was an old traditional style painter who painted a buffalo hunt,” Diacon said.

The idea was “to put these guys like warriors out there hunting, but instead of regular clothing, I'm going to put them in PPE. And instead of buffalo, I stuck that little virus in there; that iconic virus that everybody recognizes now, that little gray round sphere with the red blobs.”

Diacon’s painting captured so much attention during the “Quarantine” show that the McKeon Center asked him to present a free online workshop to demonstrate the flat style of Indian art and address its history. Diacon will host the workshop on Thursday, Sept. 17, from 5:30 to 7:30 p.m. CDT. For more information and to get the Zoom link to participate, visit the Facebook event page.

“You’ll see a style of art that at one time was really popular,” said Diacon, whose work resides in museums, including Tulsa’s Philbrook Museum and the Institute of American Indian Arts’ Museum of Contemporary Native Arts in Santa Fe, N.M. “It's kind of faded out of fashion but it's still recognized and respected and almost has a cult following.”

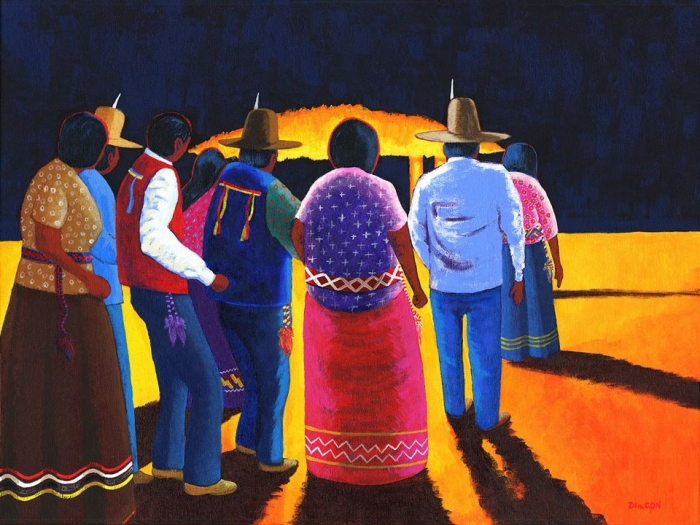

“Omvlkvt Opvnvks (Everybody Dance) Green Corn Suite” is a 2016 painting by Johnnie Diacon (Mvskoke). The painting is the cover of “An American Sunrise,” a book by Muscogee U.S. Poet Laureate Joy Harjo. (Johnnie Diacon)

“Omvlkvt Opvnvks (Everybody Dance) Green Corn Suite” is a 2016 painting by Johnnie Diacon (Mvskoke). The painting is the cover of “An American Sunrise,” a book by Muscogee U.S. Poet Laureate Joy Harjo. (Johnnie Diacon)

Native News Online chatted with Diacon about the fundamentals of flat style art, his childhood “Wizard of Oz” moment, and his painting "Omvlkvt Opvnvks (Everybody Dance) Green Corn Suite,” the cover art for the book “An American Sunrise” by U.S. Poet Laureate and Muscogee writer Joy Harjo.

There are so many cool details in your COVID Warrior piece. What are those horned things hovering above it all?

Those are like protective spirits that are overlooking the scene. A lot of your old traditional flat style paintings will have symbols, spirits, or a power overseeing everything and that's what those represent. That style of painting uses a lot of symbolism and images.

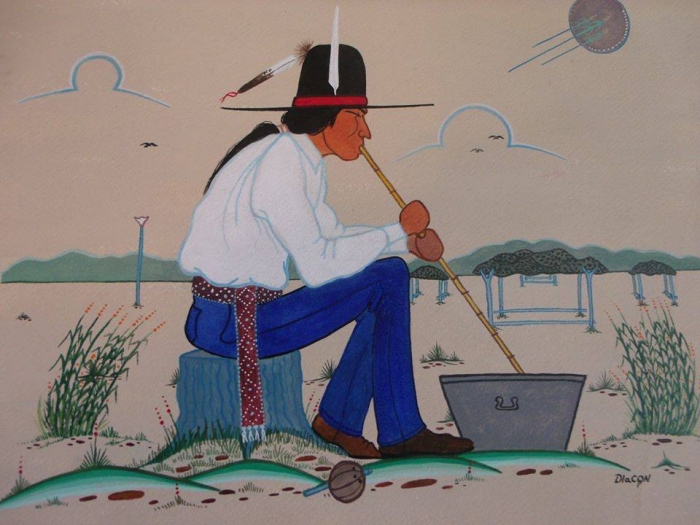

“Creek Woman Ribbon Dancer” is a flat-style painting by Mvskoke artist Johnnie Diacon. (Johnnie Diacon)It all looks kind of dreamy and psychedelic.

“Creek Woman Ribbon Dancer” is a flat-style painting by Mvskoke artist Johnnie Diacon. (Johnnie Diacon)It all looks kind of dreamy and psychedelic.

It kind of gives the impression everything's floating because you don't have a blue sky and a desert ground like you normally would. Flat style paintings are like that. They don't have a background.

You mentioned that flat style art isn’t as popular as it once was. How can you help change that?

I want to make flat style popular again, and I'd like to see more younger artists practice it because it takes a lot of discipline to get those paintings to look good. I had a non-Native artist friend who said, “Those look so easy." So he tried it and then he said, "It looks simple, but when you get in there, it’s harder than it looks."

How does the process of flat style painting differ from other methods?

In the western style of art if you're painting something and you want to give it depth, you'll mix in other colors. Like if you're painting a pair of blue pants, and you want to show all of the folds and the creases and everything and the way light hits it, you'll add different colors, maybe even colors that you don't see in something solid blue. You may add a red in there, and you'll add tints and tones to it with other colors and build up this illusion of shape and form, where in the flat painting you don't do that. If you're painting a blue pair of pants, you don't work in all the shadows and everything like that. You just paint it flat blue. Then you may outline that with a darker blue. A lot of people used to call flat style the traditional style of painting. A lot of Native art historians don't like that term “traditional” tacked on there because they think traditional is more like old, pre-ledger art.

What's the relationship between flat style painting and ledger art?

Flat style has its background in that ledger style, and the ledger style had its history back in the pictograph style that [Native artists] used to do on hides. Before Europeans came with art materials, we were producing art here forever on Turtle Island using buffalo hides and natural paints and dyes.

How did those pictographs make their way onto ledger paper?

Ledger art came about when Native Americans were taken prisoners, especially Kiowa in Fort Marion in Florida, where they were taken from Oklahoma. They were prisoners of war. [Jailers] would provide them with drawing material they'd never had before and most of it was old ledger books. That was scrap paper that they would give these Indians and then they would naturally produce things from their life and they would do that pictograph style of art, the flat way of depicting history and events onto these ledger papers, and those became real popular. Soldiers and collectors were buying them and trading them. This was just in the later part of the 19th century. So it wasn't that long ago. The style took off with the Plains Indians like the Kiowa and Cheyenne.

How did the style become ubiquitous in Oklahoma?

The flat style came about in the 1920s and 1930s here in Oklahoma with the Kiowa Six. Some of them were actually relatives of ledger artists, so they knew this style. When they started to evolve this into a painting style, they took that flat style like they were doing on the ledgers and started putting them on illustration boards and old mat boards and things like that using tempera paint and using flat colors. So you were getting images like the old pictographs or the ledger art of people with no background. It was mainly focused on the action of the subject of the painting. It evolved through the years. I got trained here in Oklahoma at Bacone College, which was a big hub of Indian Art. Bacone is where they started taking that flat style but then adding backgrounds and more to it. But they were keeping it flat.

Now I want to go way back. I read about how you were nearly blind as a child and when you were about 10 you saw flat style art for the first time in your eye doctor’s office when you finally got glasses. Can you take us back to that moment?

So I go in there and he's got me in this dark room and he brings out the glasses and I put them on, and it's like “The Wizard of Oz” when it switches from black and white to color. All of a sudden my world popped. The blurs just shrank into focus. Then he flipped on the lights and when he did, that's when I was able to see he had painting after painting hung up on the wall. The first thing I saw were these images and they were Indian, and I think that's why it stuck with me. This was in Arkansas, and it was kind of an unfriendly town for people of color, so it was unusual that these Indian images were there. I think part of the reason it stuck with me is because of some of the racism I faced. All of a sudden I could see and then here are these images presenting themselves to me and it was almost kind of a spiritual thing.

“Mvskoke Medicine Maker” is a flat-style painting by Mvskoke artist Johnnie Diacon. (Johnnie Diacon)

“Mvskoke Medicine Maker” is a flat-style painting by Mvskoke artist Johnnie Diacon. (Johnnie Diacon)

Was your doctor Native American or was he just a collector?

He was just a collector and he was known as being a collector of Native arts. And so he had all this old original flat style work. I'm sure he had work from some of the famous guys, and being a doctor he could afford that kind of art. I tried to recreate those images from memory because at the time, there wasn't any internet and there weren't any books where I could find the art, and I didn't have the opportunity to go browse his office all the time.

How did you go about teaching yourself?

I was trying all kinds of paints and everything because I had no idea how they were created. It was later on in life that I was able to find books that have these pictures in them. And I started painting that style and then I went to Bacone where they taught that and so that's where I got really into that style of painting.

Is “(Everybody Dance) Green Corn Suite,” your painting on the cover of Joy Harjo’s poetry collection, an example of the flat style?

No, that's actually more contemporary. But my training was originally in that flat style so I kind of take a lot of that and carry that over in my other work. I may add more colors to it, but I'll kind of keep that flat style aesthetic.

Did you know Harjo before she sought your painting for her cover?

I've known her for a few years. She’s a fan of my art. We weren't close friends, but if she'd be at poetry readings I'd go hear her, or I’d see her at art shows, or I'd be at the roundhouse or some ceremony and she'd be there and I'd talk to her. And I’d pass her in the hall at the Indian Clinic. She knew who I was and I knew who she was.

How did she approach you about using your work?

I posted it on Instagram or Facebook or somewhere and she saw that and she contacted me. This was before she became the U.S. Poet Laureate. She said, "I would love for that to be the cover of my upcoming book." And I thought, “Wow, that's really great,” because I love her poetry and she is one of my favorite Muscogee authors. Her last book “Conflict Resolution for Lonely Human Beings,” had a cover that was a flat style painting by one of my favorite Muscogee artists Solomon McCombs, who was also an alumni of Bacone College. He's one of my major influences. Never in a million years did I think her next book would come out and she would be asking me if she could use my art on her cover.

What aspects of McCombs’s work inspired and influenced you?

He did a lot of Muscogee subjects. Our cultural things are a little different than what most people think of as being Indian. When they think about Native Americans, most people think of Plains Indians with the headdresses and the buffalo hunts and everything, but we're from the Southeast part of the country. Moved over to Oklahoma in the Trail of Tears and we've got different ceremonies and different attire, and our dances are different. What they're doing may not resonate with what non-Native people think of when they want to buy Native art, so a lot of artists from my tribe will paint other tribes just because that's what people want for the sale. But Solomon McCombs painted ceremonies and things that were very Muscogee, and I found that to be powerful because I'm always seeking those images. I'm going to depict my people because I'm a record-keeper in a way. This art is going to be around a lot longer than I am. So when I put it out there, I want it to be what I know and where I come from.

More Stories Like This

Zuni Youth Enrichment Project Takes Top Emerging Artist Apprentices to Phoenix for Artistic Exploration and Cultural ImmersionFrom Dishwasher to Award-Winning Chef: Laguna Pueblo's Josh Aragon Serves Up Albuquerque's Best Green Chile Stew

Rob Reiner's Final Work as Producer Appears to Address MMIP Crisis

Vision Maker Media Honors MacDonald Siblings With 2025 Frank Blythe Award

First Tribally Owned Gallery in Tulsa Debuts ‘Mvskokvlke: Road of Strength’

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher