- Details

- By Valerie Vande Panne

White Mountain Apache Tribe, like much of the U.S. right now, is seeing a surge in COVID-19 cases. At the time of this writing, the tribe has 353 new COVID-19 cases and are in their second weekend of a lockdown.

“We’ve seen a spike in cases mainly due to gatherings,” Gwendena Lee-Gatewood, Tribal Chairwoman of the White Mountain Apache Tribe, told Native News Online. “I think the U.S. in general, everyone has gotten a little relaxed--’oh I don’t need to wear a mask. I don't need to wipe this down.’ The virus is moving. I know everyone is fatigued. I get fatigued of wearing masks and being careful, but we have to continue that practice.”

Want more Native News? Get the free daily newsletter today.

Derrick Leslie, Policy Unit Coordinator for White Mountain Apache Tribe Emergency Operations Center (EOC), says 68 percent of those in the community 12 years old and older have been fully vaccinated for the last month. Still, about 10 percent of COVID-19 hospitalizations are fully vaccinated people as of last week. All are considered breakthrough cases.

Now, he says, the tribe’s focus is on vaccinating those in the 5-11 year old category. As of last week Monday, November 6, 82 children had been vaccinated with the Pfizer vaccine. “It’s reassuring that we have the vaccine for our 5-11 year olds. I hope parents will take the initiative to get the kids vaccinated,” said Lee-Gatewood.

White Mountain Apache Tribe is becoming known for its contact tracing. When someone tests positive, their medical file is analyzed, and if necessary they are placed on a ‘high risk’ list--their case is managed depending on various factors, including other illnesses such as obesity and diabetes.

“We have grandmas and grandpas who don’t understand if their oxygen gets lower,” explains Lee-Gatewood. Often, she says, people think they can just stay home and power through the illness in quarantine, without realizing how sick they are or how low their oxygen level is dropping.

The tribe works closely, collaborating with multiple agencies, to go door-to-door, testing the high risk patients’ oxygen levels. This door-to-door community approach catches cases early.

“Early detection of hypoxia results in earlier hospitalization,” says Lee-Gatewood. “You catch them before they develop symptoms… It would’ve gotten worse if we waited for them to decide when to come. [Otherwise] you just tell yourself, ‘oh I don’t need to go, I'll get better.’”

Lee-Gatewood credits this door-to-door monitoring with saving lives: “Our fatalities would’ve been 80-120 deaths,” she says. “Even though we are saddened we have lost tribal members, we’ve lost 53”--significantly lower than projections. In April-May of 2020, the tribe’s COVID-19 positive rate was 8 times higher than the U.S. at that time, says Leslie.

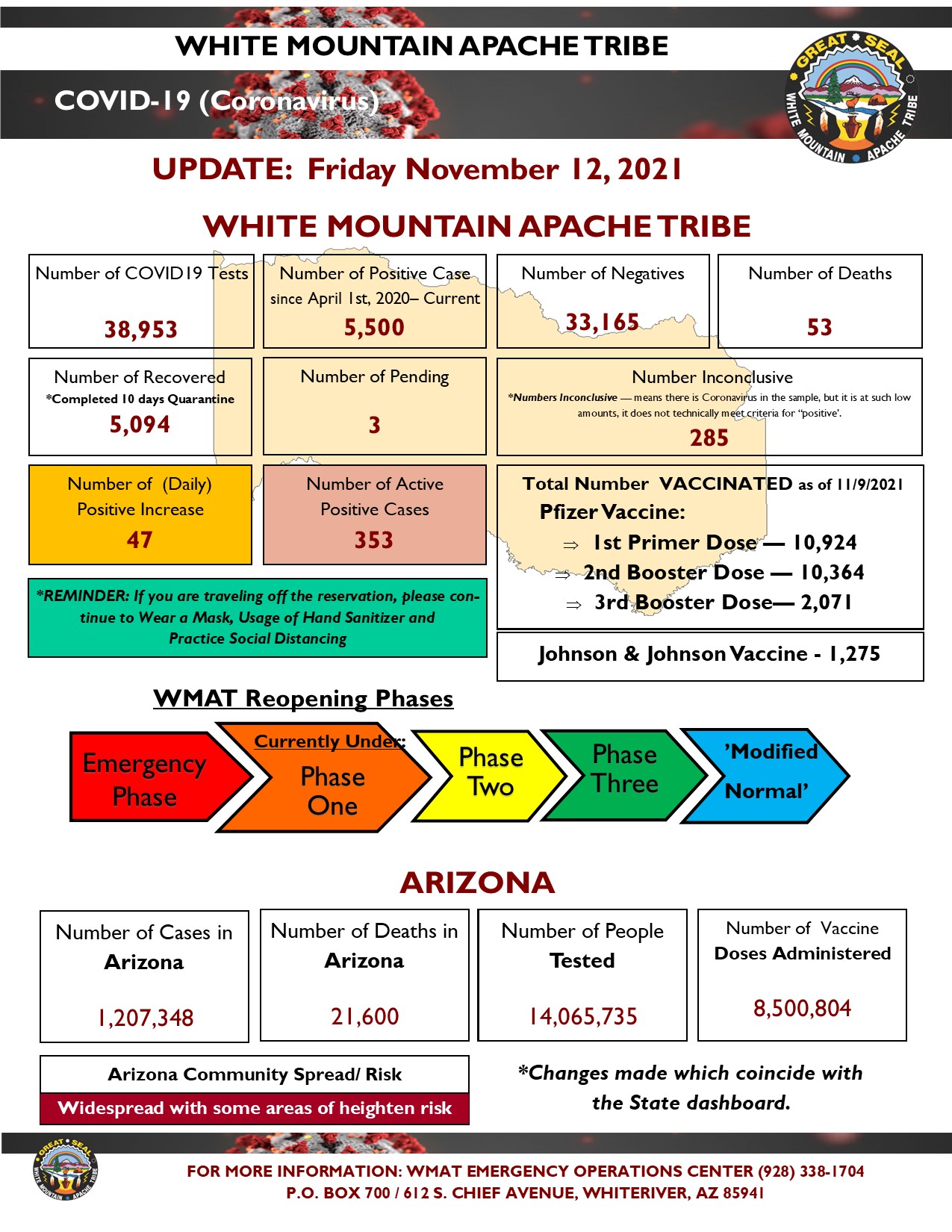

Since April 1, 2020, nearly 39,000 COVID-19 tests have been administered, 5,500 have been positive, just over 33,000 have been negative, and nearly 300 have been inconclusive, says Leslie.

Courtesy White Mountain Apache Tribe

Courtesy White Mountain Apache Tribe

Lee-Gatewood stresses the importance of the tribe’s collaboration with the Community Health Representatives (CHR), EOC, Indian Health Services, and Johns Hopkins University in the battle against COVID-19 on the tribe’s land.

The creation of high risk teams that spend their days making in-home visits, she says, has been especially helpful.

“The high risk team still go at it day in and day out, and they have done a phenomenal job going door-to-door,” says Lee-Gatewood. “A lot of non-Indigenous communities out there, all they’re doing is phone data, the new apps, but when you’re in an Indigenous community concentrated on the elderly population, you have to go above the ordinary. Here we have a different culture.”

Everyone who is diagnosed with COVID-19 receives follow-up services, including visits to each person’s home. “We make sure they’re comfortable while they’re in their quarantine,” says Lee-Gatewood, stressing the importance of a food box program that delivers 10 days worth of food and supplies, such as beans, water, cleaning supplies, and even firewood. The firewood support program is so successful that it now includes elders, single parents, and those with disabilities.

The tribe’s Community Health Representatives (CHR) has a team dedicated to each section of their land, which is about the size of Delaware and located about a 3-½ hour drive northeast of Phoenix.

“Everybody has been getting tired of the lockdowns, but it’s truly something that we have to continue,” says Lee-Gatewood. “We have our elders. They carry our culture, our heritage, and when one of them passes, a part of our culture dies with them. We can’t afford that.”

Lee-Gatewood stresses commitment to in-person care. “That’s not how contact tracing is done [in other places].”

Most tribal members have been very cooperative, she says, although some are a little resistant--but there is resistance everywhere, she says.

“We continue to promote social distancing,” says Lee-Gatewood. “We have a mask mandate that’s never been lifted… We have done so much, and we keep stressing those important things to get the people in a safe situation.”

The tribe set up an emergency alert system, where the tribe’s Emergency Operations Center can issue “phases” based on data. Currently, the tribe is in Phase 1, with a shelter in place order due to the increasing cases. “That’s when people get upset and think we’re taking away their freedom,” she adds.

“We’re all together here,” says Lee-Gatewood. “This is our house. We live in a multi-generational household. When you have grandma and grandpa in the house... you need to protect them… This is a public health response, and the quicker we respond… the better off we’ll be.”

Johns Hopkins, she says, has been integral in preparing the tribe’s COVID-19 data report every two weeks, describing the current burden, infections, hospitalizations, testing over time, and providing data to tribal leadership to help them make decisions, incorporate the data received, interpret the data, and identify if the virus is slowing down, flattening the curve, if infections are increasing, and contact tracing and tracking deaths of the vaccinated and unvaccinated. Johns Hopkins also tracks age, gender, and hospitalization status.

So far, 75 percent of the COVID-19 deaths have been 55 years old or older, says Leslie.

“I think COVID-19 has taught us a lot about time… It has given us perspective on time with family, with each other,” says Lee-Gatewood. Even though some tribal citizens were mad about the lockdown, tribal leadership encourages people to use the time to read to children, to record grandma’s stories, to teach the children, and to spend time in nature. “Even though it’s bad, you get lemons, you make lemonade,” she adds. “Yes, we’re in a lockdown, but maybe it’s a time to value grandma’s presence. Write the history down. No where else is grandma’s history--it’s in the walls of your own home.”

Lee-Gatewood also looks at the vaccine as its own miracle. “As indigenous people prayed and cried, our creator is a worker of miracles, and a part of that miracle is the vaccine, and if you look at it with the sacredness of prayers, it will be more welcome. I prayed to our creator, and our creator gave us that. Now it's up to us to help our Indigenous brothers and sisters out there. The more we take it in that perspective the better off we’ll be.”

More Stories Like This

New Mexico Will Investigate Forced Sterilization of Native American WomenUSDA Expands Aid for Lost Farming Revenue Due to 2025 Policies

Two Feathers Native American Family Services Wins 2026 Irvine Leadership Award

Bill Would Give Federal Marshals Authority to Help Tribes Find Missing Children

Indian Health Service to Phase Out Mercury-Containing Dental Amalgam by 2027