- Details

- By Mara Silvers, Montana Free Press

On the Fort Peck Reservation, a health-first approach to reducing foster care removals is getting off the ground.

Native American children make up more than a third of the foster care caseload in Montana, despite representing less than 10% of the state’s child population. While there’s a broad consensus among child welfare experts that this outsized representation is a problem, the state lacks a collective strategy to address it. The Montana Free Press series Keeping the Kids, supported by a data fellowship through the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism, explores the available data and highlights examples of local solutions around the state. This article focuses on a prenatal health intervention program getting off the ground in a northeast Montana county where the rate of children in foster care far exceeds state and national figures.

This article was originally published in the Montana Free Press.

In 2021, when now-32-year-old Natalie Van Houten took her first job as a certified nurse midwife in Wolf Point and Poplar, the two largest towns on the Fort Peck Reservation, she found some challenges she hadn’t anticipated.

For one thing, resources and community support for pregnant patients and new parents are hard to find in rural northeast Montana. And she sees more high-risk pregnancies than she expected. But perhaps most disconcerting, Van Houten said, is how often her work at Northeast Montana Health Services intersects with the foster care system, and how many children she sees removed from their parents’ custody after birth.

“That’s not what I went to school for,” Van Houten said in a December interview with Montana Free Press.

Babies under a year old are the largest age group entering the foster care system in Montana, making up about 18% of the overall caseload in 2021, according to a review by the federal Children’s Bureau. In Roosevelt County, much of which lies within the Fort Peck Reservation that is home to the Assiniboine and Sioux Tribes, children under 5 years old made up nearly two-thirds of the foster care caseload in 2022, according to the Annie E. Casey Foundation’s Kids Count Data Center.

As one of two medical providers at NEMHS who deliver babies, Van Houten said infants entering foster care often have parents dealing with substance use and addiction — health issues that are challenging to treat during pregnancy.

It’s standard protocol for Van Houten and other providers in the area to screen patients for those conditions during prenatal exams and after delivery. And if she sees signs of child neglect or maltreatment after a baby is born, such as neonatal abstinence syndrome or other signs of intrauterine drug exposure, she’s required by law to report the situation to child welfare authorities. Under contracts with the Fort Peck Tribes, child protection investigations are conducted by either the federal Bureau of Indian Affairs or the state health department’s Child and Family Services Division.

Van Houten understands the fear that leads some of her patients to not return after being drug tested on their first visit. And as a full-time midwife, she can’t also do the job of a case manager or social worker — professionals who could help connect patients with treatment, housing support and other resources. When they eventually give birth, Van Houten said, some patients don’t have plans in place to help them stay sober and keep custody of their children.

“There’s just not a lot of support. People just feel overwhelmed,” Van Houten said. “I know my patients have these barriers, but I can’t solve them by myself.”

And so, from Van Houten’s vantage, a pipeline from pregnancy to foster care continues.

In Roosevelt County, roughly 64 per 1,000 children were in foster care in 2022, according to the Kids Count Data Center. That rate, which far exceeds state and national averages, reflects an overrepresentation of Native American children in foster care across Montana. Child welfare experts say the pattern is related to a lack of critical resources, including health care access, prenatal services, addiction treatment, housing and employment.

“We’re all very focused on disproportionality. But disproportionality is the consequence of disparities that weren’t addressed in the beginning of the system,” said David Simmons, director of government affairs and advocacy for the National Indian Child Welfare Association, a national policy and training organization.

Simmons noted that in Montana, as in many states, children are typically placed in foster care as a result of issues arising from neglect. Abuse, by comparison, plays a role in a much smaller number of family separations.

“Neglect can be a number of things, but neglect is often a sign, for many families, of having disadvantages and not being able to get services or basic needs met,” Simmons said.

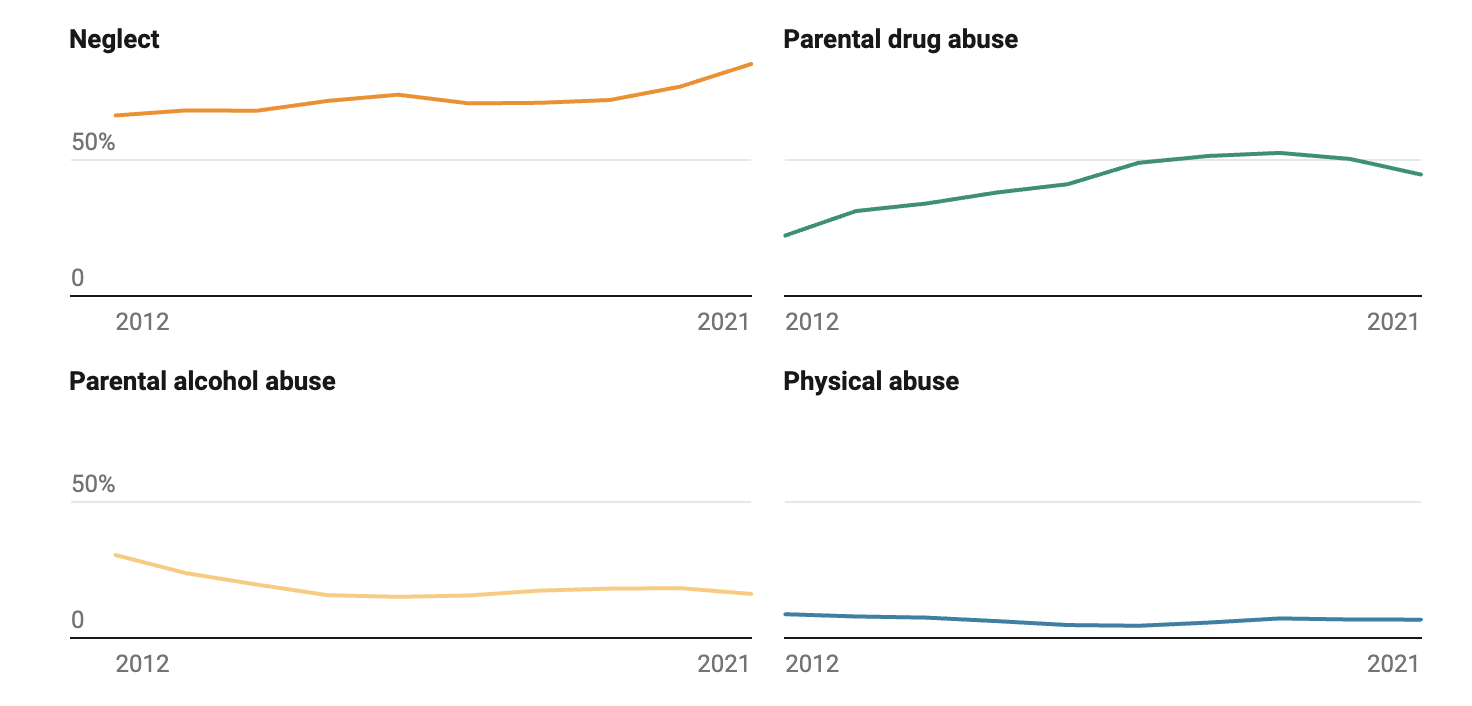

Removal Reasons for Native Children

How Montana's most common removal reasons affected Native foster care involvement,

according to the most recent decade of available data.

National Data Archive on Child Abuse and Neglect (NDACAN). (2012-2021). Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System (AFCARS), Foster Care Files 2012-2021. Chart: Mara SilversSource: National Data Archive on Child Abuse and Neglect (NDACAN)Created with Datawrapper

National Data Archive on Child Abuse and Neglect (NDACAN). (2012-2021). Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System (AFCARS), Foster Care Files 2012-2021. Chart: Mara SilversSource: National Data Archive on Child Abuse and Neglect (NDACAN)Created with Datawrapper

On a Tuesday in mid-December, Van Houten was one of a group of about a dozen medical providers, state child protection specialists and health advocates from the Fort Peck Reservation who met at the Thundering Buffalo Health and Wellness Center in Poplar, notepads and pens at the ready, to talk about new strategies to better serve struggling families and intervene in the cycle of child removals.

Van Houten’s workplace, Northeast Montana Health Services, was approved in November 2023 to join the Meadowlark Initiative, a grant-supported care model that adds behavioral health specialists and care coordinators to treatment teams for patients struggling with addiction and mental health issues during pregnancy. Care coordinators help connect patients to specialized treatment and community resources including peer support workers, food access and housing aid.

Participating organizations and community members from Fort Peck are hoping the Meadowlark program, a project of the Montana Healthcare Foundation and the state health department, can help strengthen local families and prevent situations that lead to children entering the foster care system.

At seven Meadowlark sites around Montana that had completed a two-year grant cycle, the average percentage of births resulting in a family separation prior to discharge from the hospital dropped from 2.6% to 1.4%, according to public portions of a 2022 review commissioned by MHCF. Over the grant period, the percentage of patients receiving adequate prenatal care at those seven Meadowlark sites also increased to 85% on average, up from 68% at the beginning of the grant.

Those trends would be a welcome change at Northeast Montana Health Services, Van Houten said. While the health system doesn’t currently track how many births are followed by removals at the hospital, or how many removals are related to parental addiction, she estimates that at least half of her pregnant patients show signs of substance use at some point during prenatal screenings. In Roosevelt County as a whole, roughly 31% of all pregnant patients had adequate prenatal care in 2023, less than half the Montana average, according to the county’s most recent community health assessment.

Community leaders from the Fort Peck Reservation and Roosevelt County, as in many parts of Montana, have grappled with substance use disorder as a public health crisis for years. The 2023 assessment flagged substance use disorder as “an underlying cause impacting a range of health concerns,” from “family instability” to violence, car crashes and chronic health issues.

“Despite high rates of substance use, residents of Roosevelt County are less likely than all Montanans to receive treatment,” the report said. “Our community must invest in the entire continuum of behavioral health care, from prevention, crisis response, treatment and recovery while committing to strengthening and embedding cultural and spiritual resources into this continuum of supports.”

Neglect remains the most common removal reason for all racial groups in Montana. But the number of family separations linked to parental drug use across all demographics has grown over the past decade, but decreased slightly between 2018 and 2021, according to an MTFP analysis of the most recent federal foster care data drawn from state and some tribal government records. Between 2012 and 2021, child protection workers cited parental drug and alcohol use as a reason for removal more frequently for youth identified as Native American than for non-Natives.

The Riverside Family Clinic in Poplar, one of the locations of Northeast Montana Health Services. Credit: Courtesy of Natalie Van Houten

The Riverside Family Clinic in Poplar, one of the locations of Northeast Montana Health Services. Credit: Courtesy of Natalie Van Houten

In the view of Jade Failing, a public health consultant and enrolled member of the Assiniboine and Sioux Tribes who attended the December meeting in Poplar, foster care involvement, mental health episodes and substance use disorder are “prevalent” within the Fort Peck community, and often intertwined.

“The cycle is definitely heartbreaking,” she said.

Failing is hopeful that the Meadowlark Initiative will serve parents who can benefit from additional case management and access to services. As coordinator of the recently formed Fort Peck Crisis Coalition, a community network focused on mapping local resources and identifying gaps, Failing stressed the importance of connecting people with the right tools to change their circumstances at the right time. When adults can’t get the addiction treatment, housing support or mental health care services they need, Failing said, children often suffer the consequences.

“We want to intersect where they're at and give them what they need so that they can get better,” Failing said. She described wanting to help parents pursue a process of empowerment, rather than fall into a negative spiral.

“Here's what we can do, here's how we're going to break the cycle, here's how you're going to actually help yourself,” she said.

The Meadowlark project’s approach aims to turn existing health care clinics into portals through which struggling patients can find help, and places where health care providers can alleviate the fear that a prenatal appointment will be a venue for judgment and legal consequences.

“People just don’t think that their doctor’s offices is where they would get help for transportation or housing,” said an unnamed care coordinator at another Montana Meadowlark site, as quoted in the 2022 evaluation report. “To the nurse, it’s not relevant. But to my role, it’s relevant.”

At the December meeting with Meadowlark stakeholders, large parts of the discussion focused on finding the right person for the not-yet-posted care coordinator job. Someone who approaches patients with compassion and empathy. Someone who recognizes a parent’s strengths and believes in their ability to overcome challenges.

“It’s really difficult to try to understand, ‘Well how come they just can’t do this?’ or ‘Why is it that they do this?’ Well, in most cases with our people, it’s the traumas that they have experienced. And until you go through that, most of the time you’re not going to understand it,” said Kenneth Smoker, director of the Fort Peck Tribes’ Health Promotion Disease Prevention program. “The way we look at prevention is understanding. We need to understand the people we’re serving.”

Health care providers on several other reservations in Montana have participated or are currently participating in the Meadowlark Initiative, including Blackfeet Tribal Health, Rocky Boy Tribal Health and nonprofits serving the Flathead and Northern Cheyenne reservations.

At other Meadowlark sites, the care coordinator often acts as a patient advocate and go-between with child welfare authorities, typically state workers from the Department of Public Health and Human Services. In the program’s 2022 review, evaluators found that Meadowlark providers and staff described positive relationships with state child protection workers. When interacting with care coordinators at Meadowlark sites, the review said, state workers were “receptive to taking a supportive and less punitive approach to substance use during pregnancy than they otherwise are required to take if a pregnant parent has had no prenatal behavioral health care.”

Overall, care coordinators interviewed during the 2022 evaluation described communicating with patients and following up about services as the most impactful parts of their job.

“I think they’re making more of their [obstetrics] appointments because if they don’t make it, then I call them,” one anonymous care coordinator told evaluators. “Because normally, to me, if you don’t come for your OB appointment it’s because something’s going on, not because you don’t give a damn about your baby.”

As of mid-February, the team at Northeast Montana Health Services was still finalizing the job description for the care coordinator position. They aim to post it in the coming weeks.

Disclosure: The Montana Healthcare Foundation is a major supporter of Montana Free Press.

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher