- Details

- By Jill Van Alstyne - Montana Free Press

LAME DEER—Two miles south of this southeastern Montana town, Lame Deer High School is nearly hidden among snowy, pine-topped hills. Cows graze nearby, and the school’s unofficial dog sits patiently on its haunches, waiting for a friendly custodian to feed him.

Walk inside and you will be greeted by the Northern Cheyenne emblem — a diamond with four protruding lines representing the morning star — set on a bright teal background. The walls are painted with the “Morning Star” team name and Native artwork. A student-decorated tipi anchors the commons.

You will no longer be greeted by the high school secretary, Carmelita Onebear-Williams, who died at age 57 from COVID on Oct. 31 after a short absence from school, according to the principal.

This story was originally published by the Montana Free Press on January 26, 2022. Republished by Native News Online with permission.

Onebear-Williams is one of five Lame Deer high school and elementary school staff who have died from COVID, according to administrators and staff. In addition to Onebear-Williams, a special education teacher, PE teacher, K-12 attendance/truancy officer and custodian have died from COVID, as has a school board member. The high school also recently lost a Cheyenne language teacher to another illness.

In this tribal community where many people are related, these and other deaths have deeply affected residents, school staff, and students.

“Everyone just called her Carmie,” junior Shandiin Kaline said, remembering Onebear-Williams while giving a visitor a tour of the school. “She really connected with a lot of the students. I used to have really bad anxiety, and she helped me with that.”

“We would see her every year and every day. She kind of really did everything,” said Chauncey Oldman, a junior. “We have no nurse here, and she played that role, too.”

“She was an auntie to all, getting after the students, chasing them to class, making sure they were OK, just being there for them,” said Carmie’s co-worker, Cheyenne language teacher Victoria Bearcomesout. “She would even walk around the school from one end to the other to make sure there were no kids hiding out.”

In taking lives, COVID has caused emotional loss and amplified chronic staffing shortages at Lame Deer’s public schools. As of Jan. 25, 14 elementary and 12 high school positions in the district are advertised on the Montana Office of Public Instruction’s jobs website. The elementary school currently employs 14 teachers and seven staffers, and the high school employs 17 teachers and 14 staffers.

Marcy Cobell, superintendent of Lame Deer Public Schools, in her office: “A lot of [students] live with their grandparents. We had to be cognizant that if we opened our schools, kids could bring it home to their grandma.” (Photo/Jill Van Alstyne/MTFP)

Marcy Cobell, superintendent of Lame Deer Public Schools, in her office: “A lot of [students] live with their grandparents. We had to be cognizant that if we opened our schools, kids could bring it home to their grandma.” (Photo/Jill Van Alstyne/MTFP)

“We normally don’t operate on survival mode, but I feel like we have [been] because of the pandemic, switching to online learning, the deaths in the community, and staff shortages,” elementary Principal Sherry Foote said. A Turtle Mountain Chippewa member whose husband and children are enrolled Cheyenne, Foote has been the school’s principal for 12 years.

“It’s nobody’s fault,” she said in a professional tone, with a hint of fatigue. “We were just faced with extreme challenges.”

Even amid those challenges, students are claiming what normalcy they can. In the classrooms and halls and gyms of Lame Deer’s two schools, they are learning and laughing, chatting with friends, playing basketball, cell-scrolling, or napping on their desks.

Life and school go on.

COVID AND THE COMMUNITY

Despite aggressive measures taken by the tribe and the school district to prevent viral transmission, as of mid-January, 51 people on the Northern Cheyenne Reservation have died from COVID-19, according to the tribal government website. About 6,000 tribal members live on the reservation.

The passing of Northern Cheyenne elders has devastated the community, according to Bearcomesout.

“Because of the COVID, we have lost a lot of our Native speakers,” she said quietly. “It is just so saddening to lose our elderly. They are the keepers of our wisdom and knowledge.”

Those losses make it even more urgent to teach Cheyenne culture and language to the younger generation, said Bearcomesout, one of some 300 fluent Cheyenne speakers remaining. “Our language is dying out, and we really need to do all that we can to start the healing process with this generation within the school system.”

Principal Foote said school officials began to understand the extent of COVID’s impact while applying for grants. “That’s when we started realizing that the majority of our students had lost one, two, or three people to COVID within their family dynamic,” she said.

Victoria Bearcomesout, a Cheyenne language teacher for more than 25 years at Lame Deer elementary and high schools: “Our language is dying out, and we really need to do all that we can to start the healing process with this generation within the school system.” (Photo/Jill Van Alstyne/MTFP)

Victoria Bearcomesout, a Cheyenne language teacher for more than 25 years at Lame Deer elementary and high schools: “Our language is dying out, and we really need to do all that we can to start the healing process with this generation within the school system.” (Photo/Jill Van Alstyne/MTFP)

Students and school staff have also been affected by COVID-induced school closures from March 2020 to March 2021 and sporadically since, following tribal guidance.

The switch to remote learning was motivated by responsibility to protect multi-generational families from COVID, according to district Superintendent Marcy Cobell, an enrolled member of the Blackfeet tribe.

“A lot of [students] live with their grandparents,” she said. “We had to be cognizant that if we opened our schools, kids could bring it home to their grandma.”

“Going remote was quite challenging,” Foote said. “You have to have Internet. You have to have a landline. We had to do learning packets and deliver them. It was a learning curve for a lot of our teachers.”

High school Principal Byron Woods, a non-Native from Spokane whose wife is Cheyenne and who has worked at the school for 13 years, said remote learning did not work well for students.

“Kids need that structure of in-person school. They need that social atmosphere and that routine,” he said. “The kids were getting suicidal and lonely and depressed.”

Woods said the passing rate dropped to 50-60% due to lack of student participation, which created a backlog of core class credits that students need to graduate.

students are with their responsibilities in caretaking for the community and the land,” she said. “I’m able to create science learning for Native kids that is culturally meaningful. I feel like I’m in the right place right now.” (Photo/Jill Van Alstyne/MTFP)

students are with their responsibilities in caretaking for the community and the land,” she said. “I’m able to create science learning for Native kids that is culturally meaningful. I feel like I’m in the right place right now.” (Photo/Jill Van Alstyne/MTFP)

Carol Bauer, who had taught kindergarten at Lame Deer since 1999, said remote learning was also ineffective for younger children, and that when school reopened, it was difficult to teach students with everyone wearing masks.

“When a kid can’t see your face, you can’t communicate,” she said. She retired last year partly because of remote learning.

STAFF SHORTAGES

In addition to Bauer, four other elementary staff members retired and two moved away last year. The vacancies are being covered by new hires, restructured positions, and a combined first- and second-grade class, Foote said. Employees are filling in where needed, such as the secretary managing the student information system and federal reports and the custodian doing double duty in the cafeteria.

The elementary school’s all-Native student body of 282 still needs a kindergarten teacher, first-grade teacher and culture teacher, as well as a guidance counselor, assistant principal, attendance clerk and nurse.

Down the road, the high school staff is also stretched thin.

“I’m principal, vice principal, secretary, and attendance clerk right now,” Woods said while sitting at his desk fielding phone calls about water system repairs and new student enrollment.

With 315 students in grades 7-12, the all-Native high school is looking for an assistant principal, librarian, four teachers and three special education teachers, plus teacher aides, substitutes, bus drivers and monitors, coaches, a custodian and a social worker.

Administrators said regional job fairs have not been successful in attracting employees and noted that the area’s low socio-economic and rural nature may reduce its appeal. Local residents don’t apply for different reasons, they said, such as applicants lacking computer access, having “a lot on their plate already,” or being unable to pass background checks due to minor offenses committed in their youth.

“I think that we always struggle with filling positions,” Cobell said.

A TRIBAL TOWN

Home of the Northern Cheyenne tribal government, Lame Deer is a scrappy collection of buildings set in unexpected hills that rise from the plains 100 miles east of Billings. The town’s population of nearly 2,000, distributed between town and scattered neighborhoods tucked into the hills, doesn’t reveal itself at a glance.

The people who live here and their ancestors have suffered and survived years of trauma, from the tribe’s forced removal by the U.S. government to Oklahoma in the 1870s to wildfires in recent years and a continuing plague of poverty. Yet residents find inspiration in their resilient history, especially in Chiefs Little Wolf and Dull Knife (also known as Morning Star) who helped bring their people back from Oklahoma.

The words “Out of defeat and exile they led us back to Montana and won our Cheyenne homeland that we will keep forever” are printed on tribal documents and T-shirts.

Students Brihanna Whiteman, left, and Greyson Littlehead relax in a reading nook at Lame Deer Elementary. (Photo/Jill Van Alstyne/MTFP)

Students Brihanna Whiteman, left, and Greyson Littlehead relax in a reading nook at Lame Deer Elementary. (Photo/Jill Van Alstyne/MTFP)

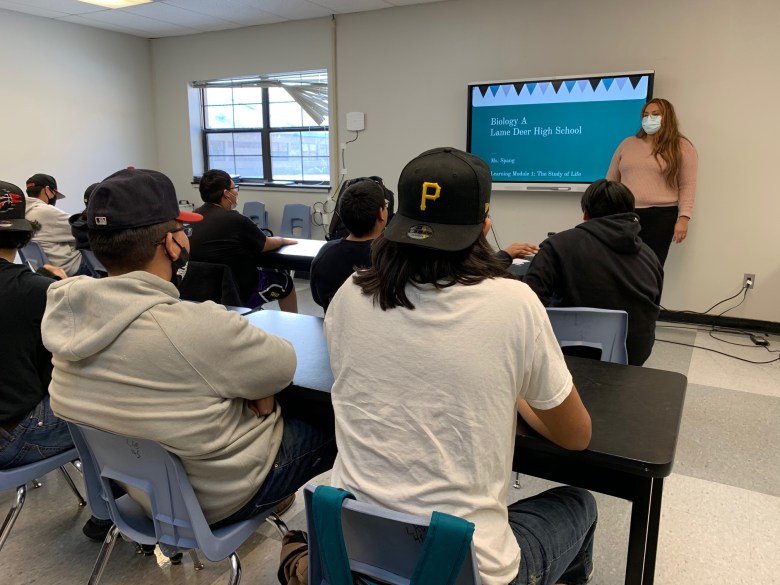

Marissa Spang, who grew up in Lame Deer, decided to return to this homeland after earning degrees at Dartmouth and the University of Washington. Seated in her classroom during a lunch break, she shared her story of becoming a high school science teacher.

Initially, “I didn’t see myself identifying in STEM as a Indigenous woman,” said Spang, who attended Lame Deer, Colstrip and St. Labre schools, and who said she is one of five Native teachers in grades 7-12.

“I was interested in becoming a teacher, but I was not interested in all the hoops” to obtain a Montana teaching certificate, she said. Her mother — who works at the school — talked her into applying for a provisional teacher license that allows her to teach while completing the required credits.

Spang creates lessons that integrate Indigenous and Western knowledge and emphasize outdoor learning and biocultural restoration, such as restoring black-footed ferrets and prairie dogs to the local landscape.

“My philosophy is connecting who students are with their responsibilities in caretaking for the community and the land,” she said. “I’m able to create science learning for Native kids that is culturally meaningful. I feel like I’m in the right place right now.”

Spang returned to the whiteboard when her students filed in along with another class whose teacher was absent. No substitute was available, so the responsibility fell to Spang.

RECRUITMENT AND RETENTION

To help fill vacancies, the school district has looked abroad.

Sijo Varghese of Kerala, India, is one of three international teachers hired this school year. The other two are from the Philippines.

Because Varghese only recently moved to the U.S., his living room in teacher housing is sparsely furnished. He courteously offered food and drink while discussing his reasons for coming to Lame Deer, far from his wife and three children in India, with whom he Skypes daily.

In addition to the money (Lame Deer teachers make $45,000 to $70,000 annually, according to the superintendent), Varghese was drawn to Lame Deer by the opportunity “to experience and explore,” he said. In the U.S. on a J-1 visa, he teaches math and physics. He holds two bachelor’s and two master’s degrees in math and education and is working on a Ph.D. He has taught for 22 years in India and Maldives.

He said he finds his greatest satisfaction in helping students with academic deficits achieve.

Math and physics teacher Sijo Varghese stands in front of teacher housing in Lame Deer: “If you give students the proper care, you will see wonders.” (Credit/Jill Van Alstyne/MTFP)

Math and physics teacher Sijo Varghese stands in front of teacher housing in Lame Deer: “If you give students the proper care, you will see wonders.” (Credit/Jill Van Alstyne/MTFP)

“I have students who do not know how to add, subtract, multiply, and divide. I am the product of a good school system. I should give something back,” he said.

“If you give students the proper care, you will see wonders.”

Lame Deer teachers emphasize project-based learning, including a student-written newspaper, student-built picnic tables and a barbecue pit for the community, and student-created media such as “The Spirit of the Horse” video, in which students and elders explain how horses help people heal.

“The sky’s the limit here,” Woods said. “It’s a great place for people if they have a passion to share, build a cool program, and do awesome projects.” Research and writing skills grow out of these activities, he said.

Kindergarten teacher Bauer also emphasized experiential learning.

“I wrapped them with crafts, songs, nursery rhymes — we just did so many physical things,” she said. “To be paid for something that you love to do is awesome.”

However, federal and state testing mandates curtailed those activities, which hastened her retirement, she said. Kindergarteners were required to learn to read and take computerized tests at a developmentally inappropriate age, according to Bauer.

“Why would they want to do that to kids? They would get frustrated as well as me. Some of them would cry,” she said. “I had to grieve the loss of kindergarten.”

Some teachers leave Lame Deer schools because they are unprepared for the discipline issues that come with trauma-exposed students, according to administrators and teachers. “Classroom management skills take years to hone,” Cobell said.

Other teachers choose to stay for the same reason.

“A lot of people come here because they want to make a difference, and this is a place where you can make a difference,” said Lame Deer elementary teacher Dawn Larsen, who had a previous career in the military and described herself as an at-risk child.

“We know what it’s like to be that kid, so we’re drawn to children like that.”

The students are also Deeanna Williams’ main reason for teaching in Lame Deer for the past 22 years.

“I grew up in similar circumstances,” said Williams, a non-Native math teacher who lives in Colstrip. “I know what it’s like to go hungry and not have enough money for clothes and transportation.”

She said teachers supported her when she was a pregnant teenager. Now Williams, who arrives at school at 5:30 a.m. each morning, aims to be that supportive teacher for her students.

She thinks Lame Deer’s tough reputation as a reservation school with behavior issues might be one reason it’s difficult to attract new teachers.

“I think what they say about us isn’t anything like what we are,” Williams said, adding that she is inspired by “the sincerity of the people that I’ve met in this area and the success stories. Their ticket to make a better life is education.”

SURVIVING AND THRIVING

Lame Deer isn’t the only school district facing staffing and COVID challenges, but those challenges are intensified in this community with existing issues and low attendance rates (76% in grades 7 and 8, and 69% in grades 9-12 this fall). Students are losing consistency, class time, and the variety that comes with classes in music, P.E., library skills and Cheyenne culture, teachers and students said.

“We’re missing out on some lessons,” high school junior Chauncey Oldman said. “If it’s an elective, I don’t mind. If it’s a core class, I might fall behind.”

Lame Deer High School juniors Chauncey Oldman, left, and Shandiin Kaline. “Everyone just called her Carmie,” Kaline said, remembering school secretary Carmelita Onebear-Williams, who died at age 57 from COVID on Oct. 31. “She kind of really did everything,” Oldman said. “We have no nurse here, and she played that role, too.” (Photo/Jill Van Alstyne/MTFP)

Lame Deer High School juniors Chauncey Oldman, left, and Shandiin Kaline. “Everyone just called her Carmie,” Kaline said, remembering school secretary Carmelita Onebear-Williams, who died at age 57 from COVID on Oct. 31. “She kind of really did everything,” Oldman said. “We have no nurse here, and she played that role, too.” (Photo/Jill Van Alstyne/MTFP)

With COVID cases rising again (there were 42 cases on the reservation as of Jan. 25), the tribe extended some emergency measures through March 15 and schools returned to remote learning for several days.

“And a special-ed teacher just resigned,” Woods said, his voice conveying both disbelief and acceptance.

Still, over the long run, the school has been able to provide stability for students, and enrollment is generally increasing, Woods said, especially “if we have a good basketball season.” (Lame Deer families can choose from five area schools: Lame Deer, St. Labre, Colstrip, Busby or Hardin.)

Cobell said they’ll continue to look for effective teachers who can “step out of [their] comfort zone and be part of the community.” Even more so, administrators are focusing on retaining the dedicated teachers they have.

Student Sheyanna Kaline, Shandiin’s twin sister, said her favorite thing about her teachers is how involved they are with activities like basketball games, selling concessions, and school dances. Despite the staff shortage and COVID, school is still a place for emotional grounding, “where everybody kind of accepts each other,” she said.

“We just had a winter formal,” Kaline added cheerfully, describing fairy lights on ornamental white deer in the blue-and-white decorated commons. Students had their pictures taken in a photo booth and requested their favorite pop and hip-hop songs. “Ever since we came back from COVID [closures], I noticed people got out of their shells,” she said.

“This year, everybody danced.”

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher