- Details

- By Patrick C. Miller

As a child growing up on the Turtle Mountain Reservation in north central North Dakota, Melanie Nadeau knew by the third grade she wanted a career in a health-related field. By eighth grade, her career goal was to become a psychiatrist.

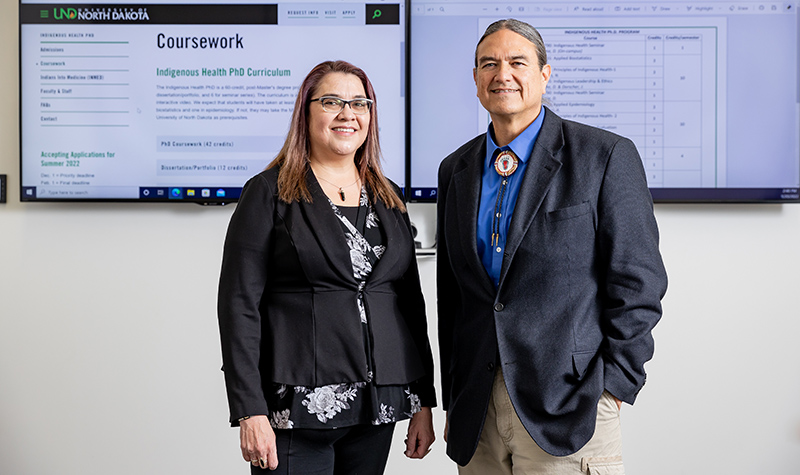

Now the director of the Indigenous Health Ph.D. Program in UND’s School of Medicine & Health Sciences (SMHS) Department of Indigenous Health, she works in the public health field as a college instructor and an accomplished researcher who specializes in social behavioral epidemiology. As a community-engaged scholar, she has nearly 20 years of research experience within the American Indian community – as well as many honors.

Want more Native News? Get the free daily newsletter today.

Although life experiences and the opportunity to participate in research intervened to change her plans, Nadeau said the outcome has been no less rewarding.

[NOTE: This article was originally published by the University of Dakota's official news sourc - UND Today. Used with permission. All rights reserved.]

“When I knew I was on the path that was meant to be, it wasn’t a struggle anymore; it seemed natural,” she related. “And my career has brought me so much joy. I have absolutely no regrets. It’s been such a wonderful journey.”

In some American Indian cultures, the turtle plays an important role in the Earth’s creation. More than 30 years ago, Nadeau – a first-generation college student – wrote a poem about her journey, which has held true, called “On a Turtle’s Walk.” It begins:

I am on a turtle’s walk

I wonder when I will get there

I hear my destiny calling

I see a road ahead

I want to get there safely

I am on a turtle’s walk

An enrolled citizen of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa, she comes from a large family that’s experienced the loss of many members over the years. Nadeau went down a list of her relatives who have died from cancer, diabetes, gunshot wounds and unintentional injuries, among other causes. They include her grandparents, mother, father, stepfather, aunts, uncles and cousins.

Feeling each loss

“Experiencing all this loss motivated me to pursue a health career,” Nadeau explained. “In the third grade, I started thinking about what I wanted to be when I grew up.”

She notes that American Indians represent a small but very diverse population, largely based in small communities.

“You feel each death because they’re in small communities,” she said. “It really translates into your life and your lived experience. This is part of our lives.

“Native people come from very disparate backgrounds and deal with a multitude of health problems,” Nadeau continued. “It becomes easy to disconnect the data from people’s actual lived experience.”

By eighth grade, she had settled on becoming a psychiatrist and began planning her career path.

“My mother told me to pursue my education because it was the one thing nobody could take from me,” she remembered. “She was my biggest cheerleader.”

After earning associate degrees at Turtle Mountain Community College in Belcourt in 1994, Nadeau enrolled at UND, got married, had a child and was one class short of completing her bachelor’s degree when her mother was diagnosed with cancer and died eight months later. She didn’t realize how much her mother’s death would affect her.

“My education came to a halt and I didn’t get my degree,” Nadeau recalled. “Everything fell apart – my family, my finances and my home.”

She returned to the Turtle Mountain Reservation and took a job in telemarketing, a field she had worked in since high school. Surprisingly, as Nadeau strived to put her life back together, the telemarketing experience would prove beneficial in getting back on a health-related career path.

A fork in the road

While continuing to further her education at Turtle Mountain Community College, in 2004 Nadeau applied for a research technician job on a biomedical research project headed by Dr. Lyle Best, a science instructor at the college and a former Indian Health Service medical doctor. He was involved in the North Dakota IDeA Network for Biomedical Research Excellence (INBRE), a National Institutes of Health-funded program administered by UND’s SMHS.

Nadeau got the job and was tasked with recruiting women on the reservation to participate in Best’s genetics study on preeclampsia, a pregnancy complication that can threaten the lives of the mother and unborn child. Meeting with more than 400 women, she persuaded all but two to participate in the study. She credited her telemarking experience with teaching her valuable interpersonal communications skills.

“I’ve always been fascinated with the social behavioral aspects of humans,” Nadeau said. “What changed with Dr. Best is that I fell in love with research, even though I’d had very little research experience.”

Best was so impressed with Nadeau’s contribution to the project that they coauthored and published a paper on how to successfully recruit American Indian women to take part in research. Best became Nadeau’s mentor and gave her advice when she was deciding whether to pursue a career in epidemiological research or continue with psychology. Ultimately, she chose research.

“Dr. Best was able to get me back on my educational pathway and I was able to finish my psychology degree at UND in 2008,” she said. “I cannot say enough about Dr. Best. If it wasn’t for him, I don’t know if I’d be where I am today.

“His lab gave me the connections I needed,” Nadeau explained. “I didn’t have the network for a career path in epidemiology.”

I pretend that my walk is going by fast

I feel brave and shall fear nothing

I touch the ground as my destiny nears

I worry about getting lost

I cry when I feel I am drifting

I am on a turtle’s walk

Nadeau received a Bush Leadership Fellowship to the University of Minnesota and in 2010 completed her Master of Public Health in community health education with a concentration in health disparities. In 2016, she earned her Ph.D. from the University of Minnesota in social behavioral epidemiology, becoming only the fifth American Indian to do so.

Career opportunities

Dr. Don Warne, associate dean at UND, chair of the SMHS Department of Indigenous Health and director of the Indians Into Medicine (INMED) program, was at North Dakota State University in 2014 when he hired Nadeau as the operational director of the American Indian Public Health Resource Center. She considers him another important mentor who helped advance her research career.

After Warne came to UND in 2018, he recruited Nadeau to work with him in developing the world’s first Ph.D. in Indigenous Health and then the first Department of Indigenous Health. Coming to UND in the spring of 2019 meant another change for her career – teaching.

Recognizing the need to strengthen her teaching, Nadeau sought out professional development opportunities. She recently completed the 2020-2021 SMHS inaugural teaching academy, an intensive faculty development program.

“I was a student for so many years that I’m very comfortable being in the position of learning,” she related. “In a lot of ways, I can lead and teach, but there are still things I need to learn. Being part of this cohort and being a scholar is a very comfortable position for me because I’m used to being in that role of learning and training.”

Nadeau credits Warne with the success and growth the indigenous health program has seen, even during the COVID pandemic.

“Dr. Warne got everybody to buy into a model that was very successful,” she said. “I don’t know of many programs experiencing a growth phase, but we are. Even in the pandemic, we’re still growing significantly.

“It’s not just our students,” she added. “Our funding and our research capacity are also increasing. We’ve been blessed as a program in the department. I’m very thankful to be in public health, especially during a time like this.”

Sometimes, Nadeau feels like pinching herself as a reminder that all that’s happened isn’t a dream. Honoring her mother’s life and continuing to work on health-related issues in the Turtle Mountain community remain important goals for her. She also believes there is always more she can do and more she can learn.

I understand that I must be patient

I say I can walk any length

I dream of being a bird, flying over all of my obstacles,

I try my hardest to get where I am going

I hope I will be successful

My name is Zhawani Ghizigo Ikwe, and I am on a turtle’s walk

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher