- Details

- By Alexander Lekhtman

This article was originally published by Filter, an online magazine covering drug use, drug policy and human rights through a harm reduction lens. Follow Filter on Facebook or Twitter, or sign up for its newsletter.

Any Wisconsin resident can now get free naloxone, the lifesaving opioid-overdose reversal drug, by mail. Like many others, the state has experienced a tragic and preventable rise in overdose deaths. An Indigenous harm reduction group is engaged in launching the mailing program, in the context of Indigenous communities suffering more from Wisconsin’s crisis than any other demographic.

Opioid-involved overdose deaths have increased by 900 percent across Wisconsin in the past 10 years. But the rate among Indigenous residents, at over 54 deaths per 100,000 population in 2020, is double that of the state as a whole.

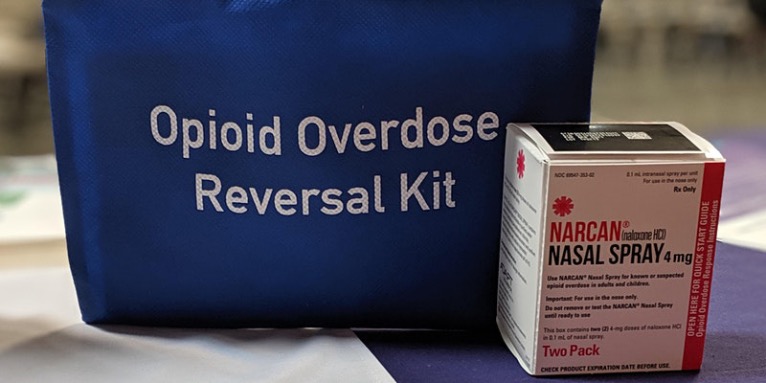

The new program will mail out free intramuscular naloxone—or, if available, the nasal spray version (Narcan). You can order through the website of harm reduction program NEXT Distro. Packaging is blank for privacy. You can also request fentanyl test strips, simple tools that let people know if fentanyl is present in the drugs they plan to use.

“Through our innovative mail-based model, NEXT’s program is responsible for over 12,000 lives saved in other parts of the United States,” said Jamie Favaro, NEXT Distro’s founder and executive director, in a press release. “We are looking forward to expanding this free, discreet service to support Wisconsinites.”

Although anyone in Wisconsin can order, it’s anticipated that rural and Indigenous communities will particularly benefit. “Making rural and tribal communities a priority in this program is vital because of the disproportionate impact of the overdose crisis in these communities, and the lack of services in these areas,” said Paul Krupski, director of opioid initiatives for Wisconsin’s Department of Health Services. “[S]ending harm reduction supplies directly to their homes improves access to harm reduction, which is more important now than ever. DHS is happy to support Bad River Harm Reduction and NEXT Distro in this effort.”

It’s also supported by Vital Strategies, a public health organization that funds various harm reduction work.

“We keep doing it because harm reduction is a life-sustaining practice rooted in our traditional values of love, respect and forgiveness.”

To operate the program, NEXT Distro is partnering with Gwayakobimaadiziwin Bad River Harm Reduction—a syringe service program run by the Bad River Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, part of the Ojibwe Nation, one of the largest Indigenous nations in North America.

Gwayakobimaadiziwin Bad River Harm Reduction is centered on and around the Bad River Reservation on the shore of Lake Superior in northern Wisconsin. Besides harm reduction supplies, it provides peer support, referrals to other services and overdose-reversal training.

“We started our community-based harm reduction program to keep our relatives, friends and neighbors from dying from opioid overdoses,” Philomena Kebec, economic development coordinator for the Bad River Tribe, said in the release. “We keep doing it because harm reduction is a life-sustaining practice rooted in our traditional values of love, respect and forgiveness.”

Kebec told Filter that beyond its critical public health benefits, the program is also a much needed job creator for her fellow tribal residents.

“This is an opportunity for us to hire people within our own community,” she said. “Bad River suffers from unemployment rates much higher than the state average. Anything we can do, especially for people who have a history of justice involvement and potentially recovering from opioid use disorder or continuing to use drugs … I’m really interested in and the tribe wants to support as well.”

The syringe program opened in 2015. According to the tribe, injection drug use had become prevalent from around 2010. Heroin and methamphetamine became more available on the illicit market, as prescription opioids and amphetamines became more restricted. Before the center opened, the community had little access to overdose prevention resources and sterile syringes. There were overdose deaths among tribal members, and people were at increased risk of HIV, hepatitis C and bacterial infections.

Drug use can be a divisive issue within the tribe, Kebec said, as some members link abstinence from drugs with their traditions.

"There’s a very strong sobriety movement in our community,” Kebec said. “The darker side of that is it’s hard for people struggling with substance use disorders to be open about it. This is especially problematic because when people are using fentanyl, they should not be using alone. It’s very dangerous to use alone, because nobody knows when you’ve stopped breathing and need to administer Narcan or call the EMTs. We’ve lost dozens of people in the last year.”

As the tribe explains in a history of the harm reduction center, centuries of warfare, displacement, forced assimilation and abuses have left its people acutely vulnerable to the harms of the drug war. Drug use, Kebec believes, is often a tool to process traumatic experiences.

Structural barriers to care also persist. Bad River tribe members struggle to find affordable housing near the reservation, according to the tribe, and many live in public housing units. A single drug conviction can permanently bar a person from public housing. And tribal health clinics may refuse to provide lifesaving medications for opioid use disorder.

“There was an awakening about how this is an incredible medication that can save lives.”

Despite these severe challenges, Kebec is hopeful that the progress made in the past eight years signals a better future for the tribe, in addition to this new project helping the wider state.

”The naloxone and overdose prevention work really speaks for itself,” she said. “Everybody in the community suddenly wanted to know about and have naloxone, because there was an awakening about how this is an incredible medication that can save lives. At this point in Bad River, naloxone is as common as aspirin or ibuprofen. People have it in their cabinets, they know how to use it. We’ve had little kids either alert someone that an overdose is occurring, or administering naloxone to their parents themselves.”

According to CDC data, Wisconsin lost an estimated 1,754 lives to overdose in 2021. The vast majority (1,427) of fatalities involved opioids, predominantly synthetic opioids like fentanyl. Opioid-involved deaths in the state have been rising for a decade. But 2020 saw a devastating surge, coinciding with the COVID-19 pandemic, that hasn’t slowed since.

In March 2022, Governor Tony Evers (D) approved a law decriminalizing fentanyl test strips, which were previously banned as drug “paraphernalia.” Milwaukee County immediately handed out 1,600 strips to outreach workers to distribute in communities. The county—the state’s most populous—suffered about a third of all overdose deaths in 2021.

The state will be also be receiving $8 million of settlement money from opioid class action lawsuits. On March 30, the state health department unveiled its plan for how to spend it, which includes $4 million for increasing naloxone and fentanyl test strip availability. Through its Narcan Direct program, Wisconsin will continue giving free Narcan to qualifying organizations—including public health agencies, syringe programs, recovery groups and methadone clinics—which then distribute it to community members. Under the plan, which must be approved by a committee of lawmakers, the state will make fentanyl test trips available through a similar program.

The NEXT Distro and Gwayakobimaadiziwin Bad River Harm Reduction initiative is another key step toward the broad harm reduction access Wisconsin desperately needs.

About the Author: Alexander is Filter’s staff writer. He writes about the movement to end the War on Drugs. He grew up in New Jersey and swears it’s actually alright. He’s also a musician hoping to change the world through the power of ledger lines and legislation. Alexander was previously Filter‘s editorial fellow.

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher