- Details

- By Kelsey Turner

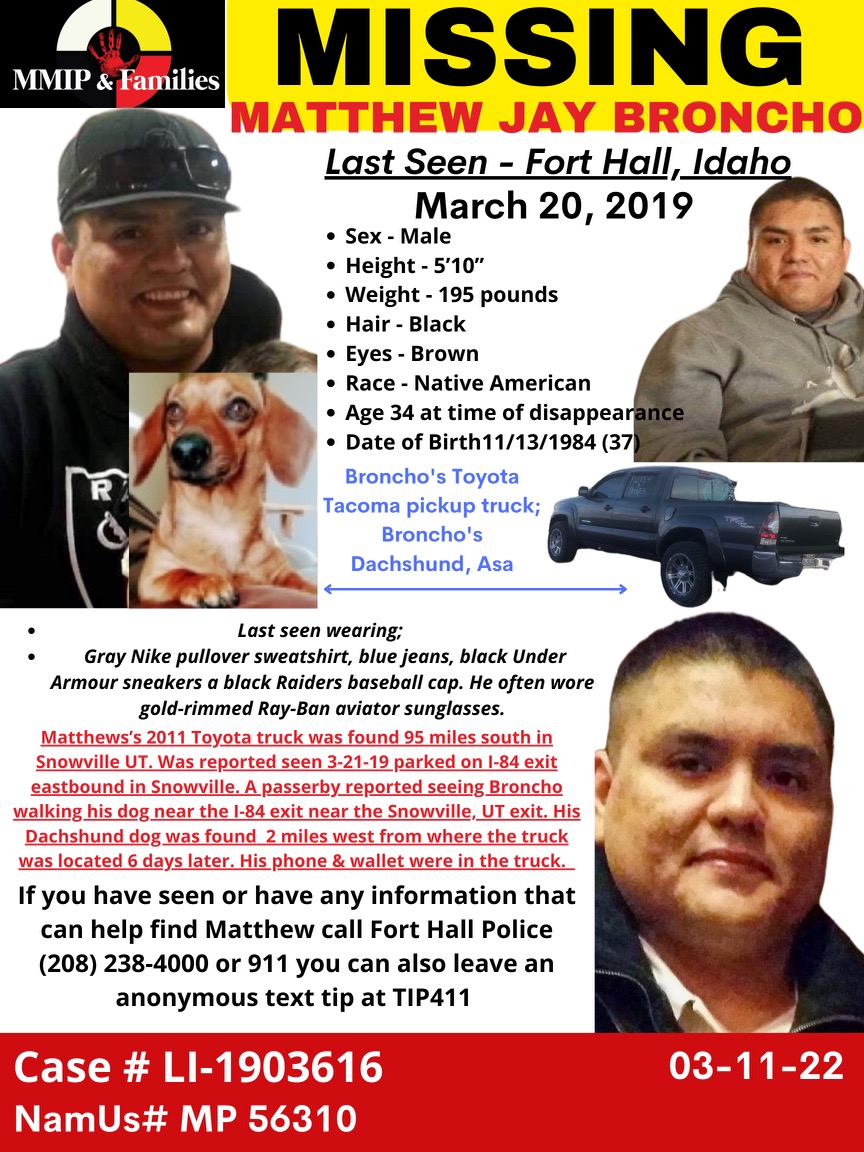

The last time Shoshone-Bannock tribal member Cynder Metz saw her son, Matthew Jay Broncho, he told her he wanted to go back to school. Matt, then 34, had a bachelor’s degree in political science from Idaho State University and was thinking of getting his master’s.

“He always talked about going back to school,” Cynder said. Matt had excelled academically and athletically in high school, she added. “I think that motivated him to pursue college and further his education.”

During college, Matt interned for the Shoshone-Bannock Agricultural Resource Management Program, where he was promoted to manager soon after graduation. He helped the tribe with various agricultural and environmental programs throughout his career, and served on the Shoshone-Bannock School Board.

He had moved back into his mom’s home on the Fort Hall Reservation in Idaho in 2018, following a breakup with his girlfriend. On March 20, 2019, Matt told her that he planned to resign from his job at the tribe’s Commodity Program, a position he wasn’t satisfied with. They talked about his future education plans. Then he told Cynder he was going into town for some errands. He picked up his dog, a dachshund named Asa, and walked out the door.

Three years later, Matt still has not come home.

“By evening time, I was concerned because he normally comes home every night,” Cynder said.

Worried that she hadn’t heard from him, Cynder tracked Matt’s phone and located it in Snowville, Utah, a town of less than 200 people about 95 miles south of Fort Hall, just over the state line. She watched the phone’s location for a day. It didn’t move.

A map of Snowville, Utah, with a mark where Matt’s 2011 Toyota Tacoma pickup truck was abandoned. (Photo courtesy of Cynder Metz)“That’s when I became more concerned,” she said. “Why would he go to Utah? I’d never heard him talk about Utah.”

A map of Snowville, Utah, with a mark where Matt’s 2011 Toyota Tacoma pickup truck was abandoned. (Photo courtesy of Cynder Metz)“That’s when I became more concerned,” she said. “Why would he go to Utah? I’d never heard him talk about Utah.”

On March 22, Cynder called Matt’s dad, Jimmy Broncho, to ask if he had seen Matt. He hadn’t. Jimmy, in a state of panic, started calling Utah hospitals and police departments. “Not knowing what’s going on with your child,” Jimmy said. “Your mind just races. My sense was, time is of the essence.”

Cynder decided to drive with her sister that evening to the phone’s location in Snowville, where they found Matt’s 2011 Toyota Tacoma pickup truck sitting along an exit ramp off Interstate 84. His phone and wallet were in the truck’s center console. It looked like he had eaten pizza for lunch, based on the pizza box and Monster energy drinks in the truck, Cynder said.

She went into town and gave pictures of Matt and his dog to employees at the town’s diner and gas stations. That night, she called the sheriff’s office in Box Elder County – the county Snowville is in – and reported Matt missing. Then she drove back home, hoping her son would be there by the time she got back.

When she arrived home in Fort Hall the next morning and Matt still wasn’t there, she filed a missing-person report with the Fort Hall Police Department. She also followed up with her report at Box Elder County. The next day, she drove back down to Snowville. “By that time, I was hysterical and emotional,” she said.

Cynder, along with Jimmy and other family members, began searching Snowville for any sign of Matt. “We were out there in the sagebrush, walking. Walking through the mountains there. At that time, the weather was snowy and rainy, so it was tough and very cold. We returned to that area daily for a couple of weeks.”

Six days after Matt’s disappearance, a passer-by found his dog, Asa, two miles west of where the truck was found. Asa was alive and well. Cynder then contacted the Box Elder Sheriff’s Office again. “At that time, they told us they were going to initiate the search and rescue,” she said.

(Photo Courtesy of Roxanne White)The search and rescue moved quickly at the beginning, with resources from both the Box Elder County law enforcement and the Shoshone-Bannock Tribes Fish and Game Department. “They put over thousands and thousands of man-hours there,” said Brandon Yates, the Box Elder County detective currently working on Matt’s case. “They were flying drones. The family had come down. We had our search and rescue out there, we had our horse posse out there. Any little tip we had, we would go and check that out.”

(Photo Courtesy of Roxanne White)The search and rescue moved quickly at the beginning, with resources from both the Box Elder County law enforcement and the Shoshone-Bannock Tribes Fish and Game Department. “They put over thousands and thousands of man-hours there,” said Brandon Yates, the Box Elder County detective currently working on Matt’s case. “They were flying drones. The family had come down. We had our search and rescue out there, we had our horse posse out there. Any little tip we had, we would go and check that out.”

But now, after three years, Matt’s parents are unsure where the investigation stands. His case has passed through multiple detectives in both Fort Hall and Box Elder County. “It’s just been handled by too many people now,” Cynder said. “It’s assigned to a third detective in Box Elder. And I don’t think he’s familiar with the case.”

Yates was assigned to Matt’s case in mid-March after staffing changes in the department. He is taking steps to learn about the investigation. “I’ve read about 44 of the 61 parts of it. It’s all about reading the story,” he said. He also spoke to some people who have been involved with the case, including another detective and the sheriff. “That’s about what I know.”

Cynder and Jimmy are not the only Shoshone-Bannock tribal members coping with the loss of a loved one. Jimmy estimates there are around five or six unsolved cases of missing and murdered people on the Fort Hall Reservation, with the most recent one a woman found dead of undetermined causes last spring.

“And there will probably be more,” he said. “It doesn’t happen every day, but when it does happen, it is news and it will stir interest, and then it kind of just fades away.”

Matt’s disappearance opened Jimmy’s eyes to how big the issue of missing and murdered Indigenous people really is, he said. The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) estimates there are about 4,200 cases that have gone unsolved. Native communities experience disproportionately high rates of assault, abduction, and murder – rates that advocates say are tied to a “legacy of generations of government policies of forced removal, land seizures and violence inflicted on Native peoples,” the BIA website states.

Cynder Metz (left) and Matt’s sister, Elise Benally, march for Matt in the Eastern Idaho State Fair Parade in Sept. 2021. (Photo Courtesy of Cynder Metz)When Matt first disappeared, a local Fort Hall Missing and Murdered Indigenous People (MMIP) group called Carrying the Message reached out to Cynder. The group helped organize a prayer walk and run for Matt in June 2019. Last year, for the second anniversary of his disappearance, the group held a balloon release to bring awareness to the MMIP crisis. This year, Cynder and Jimmy attended a vigil and prayer walk for Matt on March 18 and 19 in Fort Hall.

Cynder Metz (left) and Matt’s sister, Elise Benally, march for Matt in the Eastern Idaho State Fair Parade in Sept. 2021. (Photo Courtesy of Cynder Metz)When Matt first disappeared, a local Fort Hall Missing and Murdered Indigenous People (MMIP) group called Carrying the Message reached out to Cynder. The group helped organize a prayer walk and run for Matt in June 2019. Last year, for the second anniversary of his disappearance, the group held a balloon release to bring awareness to the MMIP crisis. This year, Cynder and Jimmy attended a vigil and prayer walk for Matt on March 18 and 19 in Fort Hall.

But while Cynder and Jimmy continue raising awareness for their son, they feel law enforcement has stopped prioritizing Matt’s case.

“I feel like there isn’t a plan in place,” Cynder said. “There are no resources available to identify information. It’s just like it’s at a standstill right now. And nobody’s doing anything.”

Detective Yates said the tips they have received so far have led to nothing. “We’ve exhausted just about every avenue,” he said. “We’re just kind of waiting for tips and any new information.”

Jimmy and Cynder have approached the Shoshone-Bannock Tribes’ tribal council to encourage them to continue working on the case. “We’re given a big smile, but yet nothing changes,” Jimmy said. “We hear excuses – ‘Oh well, we’re short-staffed,’ or ‘we can’t talk about it.’ We’re kind of getting stonewalled on the reservation side.”

The Fort Hall criminal investigator assigned to Matt’s case was unable to speak with Native News Online for an interview due to tribal restrictions regarding talking to the press.

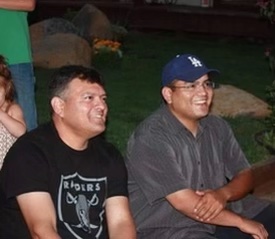

Jimmy (left) and Matt Broncho on the Fort Hall Reservation in Sept. 2018. (Photo courtesy of Cynder Metz)Cynder and Jimmy still hope they will find their son. “Every day I think about Matt, and I pray that someday we’ll find him and he’ll come home safe,” Cynder said. “Trying to get through it is really hard. I’m thankful for all the support from family and the Fort Hall MMIP Carrying the Message group.”

Jimmy (left) and Matt Broncho on the Fort Hall Reservation in Sept. 2018. (Photo courtesy of Cynder Metz)Cynder and Jimmy still hope they will find their son. “Every day I think about Matt, and I pray that someday we’ll find him and he’ll come home safe,” Cynder said. “Trying to get through it is really hard. I’m thankful for all the support from family and the Fort Hall MMIP Carrying the Message group.”

Jimmy also keeps praying for Matt, wherever he may be. “I’ve tried fasting in his honor to see if that would lead me to maybe a higher depth of prayer, so maybe I could get an answer of where he is,” he said. “Just to grasp onto anything.”

Cynder’s advice to others with missing loved ones is, “Don’t wait.”

“When somebody disappears or you’re missing somebody, you need to get that information out as soon as possible,” she said. “Get it out to the police department, get it out to media, and start searching.”

If you have information about Matthew Jay Broncho, call the Fort Hall Police Department at (208) 238-4000 or the Box Elder County Sheriff’s Office at (435) 734-3800 or leave an anonymous text tip at TIP411

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher