- Details

- By Elyse Wild

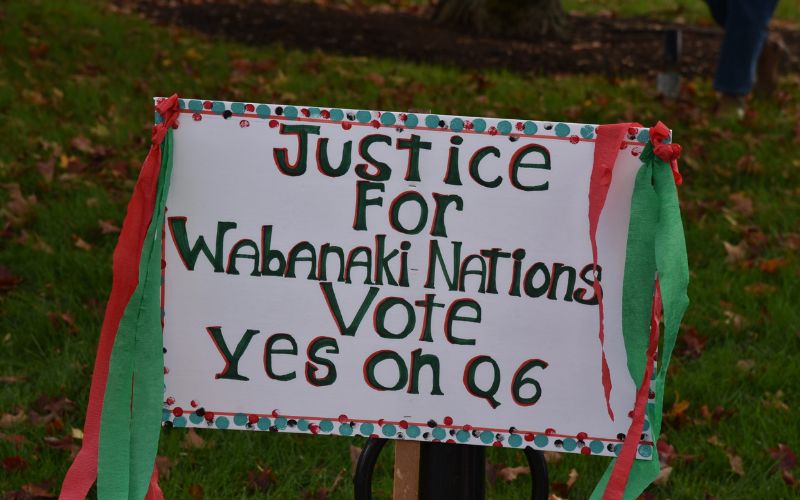

On the ballot is Question 6, a constitutional amendment that, if passed would require the state to print the full text of the Maine State Constitution, including Maine’s original treaty obligations to the Wabanaki Nations that have been missing from printed versions for more than 100 years.

Maine remains the only state in the country that does not extend recognition to its federally recognized tribes, which include the Maliseet, Micmac, Penobscot and Passamaquoddy, collectively known as the Wabanaki Nations.

The issue dates back to 1980, with the passing of the Indian Land Claims Settlement Act. The act was a response to litigation declaring that under federal law, the Passamaquoddy Tribe and Penobscot Nation had legal claim to a substantial amount of land in the state.

The act was intended to provide funds and outline a process for tribes to buy land to replace the unlawfully seized land. However, the wording limits federal Indian law from automatically applying to Maine’s tribes. It places them under state jurisdiction, effectively restricting the tribes’ sovereignty — cutting them off from federal funding and benefits that are essential to the well-being of tribal communities. More than 150 federal Indian laws passed since 1980 that do not apply to the Wabanaki tribes.

The economic impact of restricted sovereignty on Maine’s tribes was documented in a 2022 study by the Harvard Kennedy School. The study concluded that the Maine Indian Claims Settlement Act has severely hampered economic development for the Wabanaki Nations and the surrounding non-tribal rural areas. According to the study, since 1989, per capita income among Maine tribes has grown just 9 percent, far behind the 61 percent per capita growth among the rest of Indian Country.

Support for Wabanaki’s sovereignty in Maine is widespread and bi-partisan. In 2022, the state saw two failed attempts to expand Wabanaki sovereignty in 2022. This past June, another attempt was made when LD 2004, a bill that would have retroactively enacted federal legislation that excluded tribes in Maine, passed in the Maine House and Senate, only to be vetoed days later by Governor Janet Mills.

In explaining her veto, Mills stated, “I fear it would result in years, if not decades, of new, painful, complex litigation that would only further divide the state and our people.”

The Wabanakoi tribes have lived in what is now Maine for more than 15,000 years. Their populations have been depleted by 98 percent.

On September 29, the Maine Conservation Voters held a lunch and learn titled, “Restoring Wabanaki History in Maine at the Ballot Box,” with guest speaker Maulian Bryant, Penobscot Nation Ambassador and President of the Wabanaki Alliance Board of Directors.

On the lunch and learn, which was recorded and can be watched here, Bryant said printing the state’s constitution to include original treaty obligations is important for government transparency.

“People understanding the history, commitments, and obligations the government made the Wabanaki tribes is essential for healthy relationships between the Wabanaki and the state of Maine,” Bryant said. “We were written into the Maine constitution... you need to be a sovereign government to be written into treaties, so the fact that we were recognized as sovereign nations at one point is significant.”

In a video campaign advocating for Maine voters to vote yes on Question 6, Dr. Darren Ranco, Chair of Native American Programs at the University of Maine and citizen of Penobscot Nation, said that an understanding of the state’s original promises is essential for the Wabanaki Nation moving forward.

“I want to tell you what this question means to be as a Penobscot citizen and as an educator,” Ranco said. “I’ve heard people say this is an unimportant distraction, or it’s not meaningful, because these sections remain in full force of the law. I suggest instead that it is all about meaning and how we as Wabanaki people form our social contract with the state of Maine.”

More Stories Like This

Navajo Council Committees Tackle Grazing Enforcement, Code RevisionsU.S. Must Fulfill Obligations by Protecting Programs

50 Years of Self-Determination: How a Landmark Act Empowered Tribal Sovereignty and Transformed Federal-Tribal Relations

Trump Veto Stalls Effort to Expand Miccosukee Tribal Lands

Oneida Nation Responds to Discovery Its Subsidiary Was Awarded $6 Million ICE Contracts

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher