- Details

- By Nanette Kelley

SACRAMENTO, Calif. — A new bill in California, titled AB-275 Native American cultural preservation (2019-2020), would enable tribes to reclaim human remains and funerary objects, and could potentially serve as a gateway legislation for tribes and tribal members to manage their own ancestors’ legacies.

“One bill can’t correct five hundred years of misrepresentation,” said Assemblymember James C. Ramos (Serrano/Cahuilla tribes) (D-Highland), the Chair of the Select Committee on Native American Affairs and the first California Native American elected to the Legislature, in an interview with Native News Online.

Currently in the senate, AB-275 could help fulfill one of the most primary needs of Indigenous peoples: repatriation. The bill was designed to strengthen the California Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act of 2001 by revising various definitions including, among others, “the definition of ‘California Indian tribe’ to include both a tribe that meets the federal definition of Indian tribe and a tribe that is not recognized by the federal government, but that is a native tribe located in California that is on the list maintained by the commission,” as well as the “definition of ‘museum’ to specify it receives state funds.”

Introduced by Assemblymember Ramos with coauthor Assemblymember Lorena Gonzalez (D-San Diego), AB-275 would also “revise and recast the process by which a direct lineal descendent or a California Indian tribe can request the return of human remains or cultural items.”

The legislation was passed by the house on May 23, 2019 (78-0) and has been in a lengthy amendment process over the inclusion of both federally and non-federally recognized tribes listed on the Native American Heritage Commission list of California tribes.

“AB-275 will start to bring clarity,” said Ramos, who indicated they reintroduced amendments and were able to garner support from those who had concerns with the original bill. “The language was changed for the best and now includes everyone, I never tried to cut anyone off.”

To expedite repatriation, AB-275 was designed to require state funded institutions to “revise and recast the process of creating the inventories and summaries by, among other things, requiring consultation with California Indian tribes during the creation of the preliminary inventories and summaries.”

In contrast, unlike state institutions, Agua Caliente Cultural and Barona Museum’s material culture collections are good models of collections controlled by the respective tribal members. Not only is tribal accessibility respected, these collections are well catalogued.

“Our primary audience for the museum is the tribe itself, a teaching tool for youth, a resource for adults, and a legacy for elders; our secondary audience is the broader public, everyone is welcome, but our tribal members are the priority,” said Steven Karr, the executive director of the Agua Caliente Cultural Museum.

The museum, owned and managed by the Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians, has 48,000 square feet of space with 10,000 square feet of exhibition space dedicated to the history and cultures of the Agua Caliente peoples. As their emphasis is on creating a legacy that will stand for many decades, “The tribe’s museum collection will grow over time,” said Karr.

“Access is important, and our efforts are to always provide access to tribal members when requested,” he said.

Laurie Hedley, the director and curator of San Diego County's first museum on Indian land, the Barona Cultural Center and Museum, said, “The Barona Museum (Barona Band of Mission Indians- Kumeyaay/Diegueño) is one hundred percent accessible to the public, and one hundred percent of the cultural material and close to ninety-nine percent of the archives are catalogued. All researchers are welcome, and we try to make sure we are completely accessible.”

While some museums are decolonizing with the help of tribal members, regarding state institution inventory research, Hedley said, “I’m afraid if we go in there to another collection and it’s not catalogued properly, a search would only turn up like sixteen things. It would be another disaster.”

“So far as cataloguing, that’s something we continue to work on,” said Ramos.

Ramos suggested many of the problems associated with state museum collections may be solved by the addition of California tribal members to the University of California system’s campus-level committees, spurring change from within.

“They haven’t been able to recruit Native Americans to these boards, or maybe haven’t even tried to recruit,” he said.

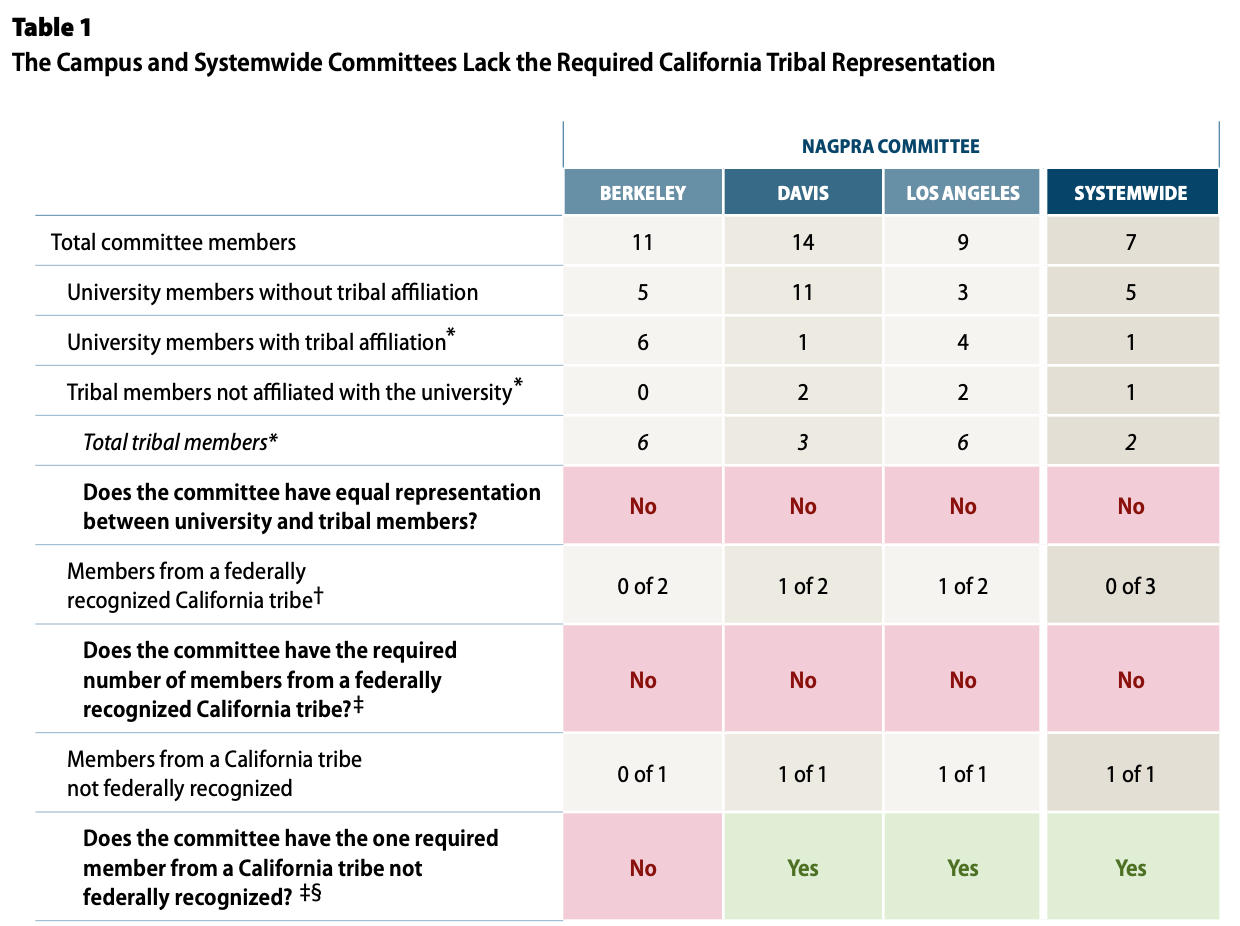

According to a recent report from the Auditor of the State of California on the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, the campus-level committees in question that are responsible for repatriation decisions do not meet CalNAGPRA’s requirements for tribal representation. Tribal members should have representation equal to the number of university members on the campus and systemwide NAGPRA committees. As a result, the auditors found, campuses are not adequately overseeing their return of “hundreds of thousands of remains and artifacts.”

“We need to integrate these boards in the correct manner,” Ramos said. “And we need to make sure the Native Americans on those boards are California Indians.”

More Stories Like This

Native News Weekly (August 25, 2024): D.C. BriefsNavajo Nation Mourns the Passing of Former Vice President Rex Lee Jim

Deb Haaland Earns Endorsement From Communications Workers of America Local 7076

University Soccer Standout Leads by Example

Two Native Americans Named to Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee's“Red to Blue” Program

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher