- Details

- By Erin Fehr

On Monday, April 8, 2024, people across a large swath of the United States will experience a total solar eclipse. For many, it will be a once-in-a-lifetime experience. For the Indigenous peoples of North America, it will be one of many solar eclipses that have been witnessed by their people since time immemorial. Before science was able to explain the phenomenon surrounding a solar eclipse, many tribes created myths to explain the celestial events in their own way.

The Cherokees have a story of a giant frog that swallows the sun, which causes the earth to go dark. Men and women needed to scare the frog into spitting the sun out, so they created as much noise as they could. The men shot rifles into the air and pounded on drums while the women banged on pots and pans and used shell shakers. Once the frog released the sun, the noise turned into a celebration.

The Choctaws have a similar story, but this time, a black squirrel is trying to eat the sun. “Fvni lusa hushi umpa!” (The black squirrel eats the sun.) They made noise to scare the black squirrel, with the men firing rifles while the women banged on pots and pans as loudly as they could. Once the sun returned, they cried, “Fvni-lusa-hosh mahlatah!” (The black squirrel is frightened!)

The Kumeyaay people of Southern California and Northern Mexico tell a story of Frogs in Love to explain the solar eclipse. All of the animals were going to the wedding ceremony for the Sun and Moon. On the way, two frogs were in love and stopped to mate in the pond. When they got back on land, the female frog noticed her stomach getting bigger, so she jumped back into the pond. The pond became filled with pollywogs. The frogs realized they had to warn the Sun and Moon. They rejoined the others and explained what had happened. The universe would be thrown off balance if there were many suns and moons; they could not marry. So, the Sun and Moon decided they would take turns being awake. The Moon would sleep while the Sun was awake. The Sun would sleep while the Moon was awake. The only time this is not true is when an eclipse happens.

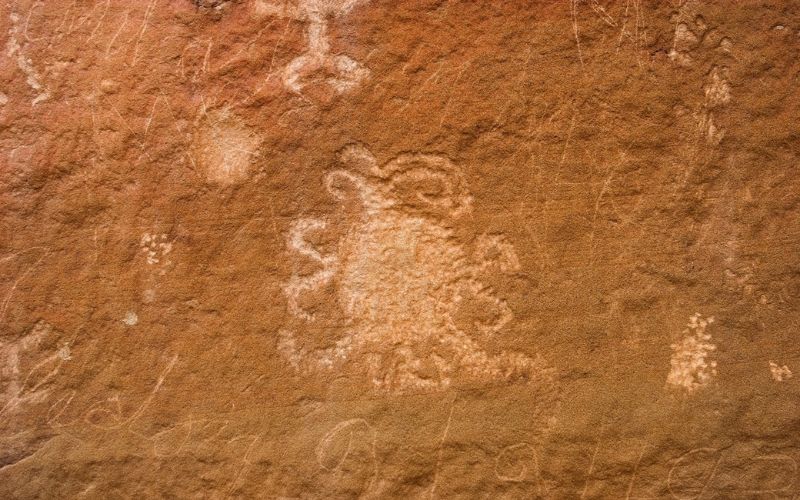

Rock of the Sun petroglyph, Chaco Canyon. (Courtesy of National Park Service)

Rock of the Sun petroglyph, Chaco Canyon. (Courtesy of National Park Service)

In addition to the myths surrounding a solar eclipse, there is archaeological evidence of Indigenous North Americans recording their experiences. The Ancestral Puebloan Peoples may have been the first to leave behind physical evidence of their witness to a solar eclipse when they created the Rock of the Sun petroglyph in Chaco Canyon. The petroglyph depicts the sun’s corona, which is seen during a total solar eclipse. Scientists believe that the petroglyph dates back to the eclipse of July 11, 1097.

The Chumash people of Coastal Southern California have a long history of studying the celestial bodies. Alaxuluxen, or the Chumash Painted Cave State Historic Park, near Santa Barbara, California, has evidence of a solar eclipse witnessed by the Chumash. Scientists believe the rock painting of one large black disk with two red circles underneath indicates the total solar eclipse that occurred on November 24, 1677, when Mars and the star Antares were visible.

Chumash Painted Cave (Courtesy of Library of Congress)

Chumash Painted Cave (Courtesy of Library of Congress)

The solar eclipse of August 7, 1869, that passed through Montana, North Dakota and South Dakota was recorded by various Lakota record keepers. A winter count was kept to record one important event per year. The winter counts kept by Lone Dog, The Flame, The Swan, and Rosebud all record the total solar eclipse that they witnessed as a significant event in Lakota history.

Solar eclipses have also been central to historic events, like the birth of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy. On August 22, 1142, a solar eclipse occurred near modern-day Victor, New York, where the Five Nations were meeting to form the Confederacy and end the strife among their Nations. Oral history suggests that the fifth nation, the Onondagas, were the last hold-outs, but the total solar eclipse convinced them to join in bringing peace to the region.

In 1806, Tenskwatawa, also known as The Shawnee Prophet, was in conflict with then-Governor of Territorial Indiana William Henry Harrison, who later became the 9th President of the United States. Harrison was upset by the call for tribal unity in the region, fearing that a united front would be harder to overcome. He challenged Tenskwatawa to prove himself.

Tenskwatawa Courtesy (Courtesy of National Portrait Gallery)

Tenskwatawa Courtesy (Courtesy of National Portrait Gallery)

“If he is really a prophet, ask him to cause the sun to stand still, the moon to alter its course, the rivers to cease to flow, or the dead to rise from their graves. If he does these things, you may believe that he has been sent from God.”

In response, Tenskwatawa predicted an eclipse of the sun in 50 days. 50 days later on June 16, 1806, a total solar eclipse hid the sun across parts of Indiana, solidifying his position of authority.

Different perspectives even appear in Native languages. In Shawnee, the eclipse is known as the black sun, mukutaaweethee keeshohtoa. The Yup’ik language describes a solar eclipse as the sun dies or weakens, akerta nalauq. The Osage language uses the phrase mie phi’n’-ge, meaning the sun disappears. The Choctaw language describes the eclipse as the sun goes away: hvshi ninak aya. Others are more descriptive, like the Klamath phrase loq slo’ki, meaning the grizzly bear eats. The Kumeyaay say enyaa wesaaw, which means nibbles the sun. In Anishinaabe, an eclipse is described in two ways—aatenaagozi (appear to be extinguished) or aateyaabikishin (be darkened).

Regardless of where you are along the path of the solar eclipse this April 8, it is certain that the Indigenous peoples of Turtle Island have a tribal myth to explain the phenomenon, centuries-old records of a previous occurrence, or memories of a historic event that further creates significance to a truly wonderous sight to behold.

Erin Fehr is Yup’ik and the assistant director and archivist at the Sequoyah National Research Center at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock.

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher