- Details

- By Chadd Scott

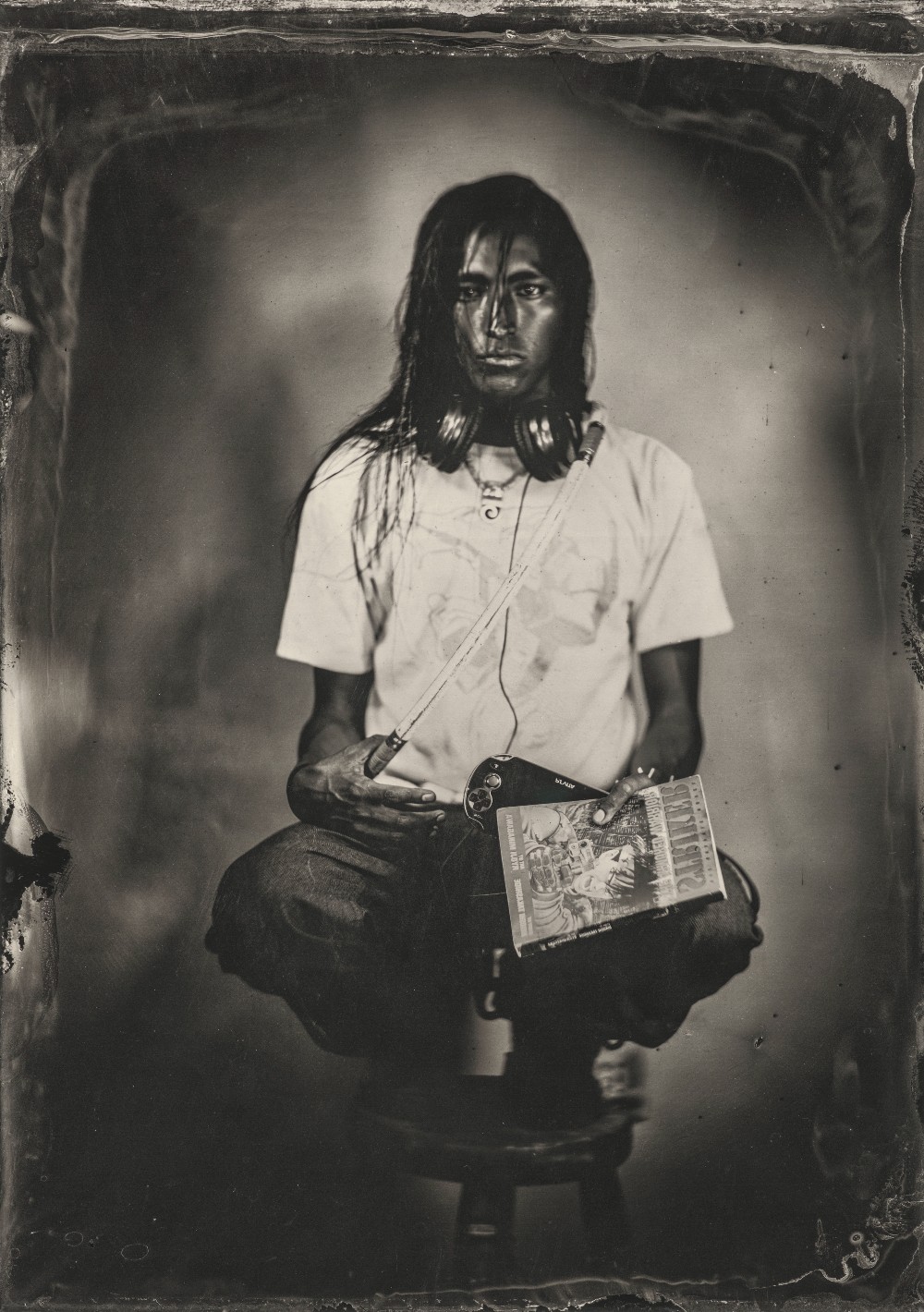

There is a perception of Native people still widely held in the United States: Google Image search “Native American” and at the top of the search will likely be archaic photos of Native Americans taken by Edward Curtis–tin types and sepia toned. These outdated images continue to inform a style that over a century later dominates museum exhibitions and the tops of Google searches: the Indian in a headdress, bareback on a horse, etc. Diné photographer Will Wilson uses the very tin type and sepia that froze Native Americans in the past to shatter the myth and bring Natives very much into contemporary, modern art.

Wilson’s latest exhibition, In Conversation: Will Wilson, investigates the legacy of historical photographs on the representation of Native peoples in North America. It opened on July 9 at the Delaware Art Museum.

“People don’t want to deal with the traumatic reality of history, of genocide, of attempted ethnic cleansing,” Wilson told Native News Online. “They’d rather see these noble, beautiful images of a ‘better time.’ I want to make the case that we’re still here doing interesting and important things.”

Wilson’s work strikingly portrays contemporary Indigenous people, using a similar photo process to those used historically. The resulting contradiction – contemporary Native people photographed historically – demands onlookers examine how they imagine Native people, what myths they hold on to, and why those myths exist.

Alongside portraits previously taken by Wilson, In Conversation debuts new images he created from a May visit with citizens of the Lenape Indian Tribe of Delaware and the Nanticoke Indian Association.

“I didn’t know much about that cultural history, but it’s always amazing to go as a photographer with an open mind and engage a community and see how people want to represent themselves,” Wilson said. “Something that’s happened recently, and it’s part of this whole reckoning around race and acknowledgment and land acknowledgments with museums in particular – thinking about who the original stewards of space are – people have seen this project as an opportunity to do a little bit more than just put a statement on a gallery entrance. To use [my photography] as a vehicle to reach out to a community, establish a relationship, and also acknowledge through photography the relationship of the Indigenous people who are still very much around and have a stake in how land is managed and how representation happens.”

Wilson’s images of the Lenape and Nanticoke will be used by the Delaware Art Museum moving forward to increase representation of Indigenous people within its walls. The museum hosted a powwow and storytelling event to coincide with the exhibition opening to further demonstrate its increased commitment to acknowledging and promoting Indigenous culture.

In Conversation: Will Wilson is on view through September 8, 2022. Wilson has another solo exhibition through December 11, 2022, at the Southeast Center for Contemporary Art in Greensboro, North Carolina. His work is also displayed in an upcoming group show at the Utah Museum of Fine Arts in Salt Lake City, and in the recently reopened permanent exhibition at the Museum of Indian Arts and Culture in Santa Fe.

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher