- Details

- By Shaun Griswold

At the premiere of the new short film, Following Enchantment’s Line, Jock Soto, the Diné and Puerto Rican ballet dancer, could be seen gliding underneath vast blue New Mexico skies — the only time the audience saw him dance.

This article was originally published in High Country News.

Afterward, as the lights went up in Santa Fe’s Lensic Performing Arts Center, lightning cracked the summer monsoon clouds. Hard rain echoed inside the theater, as Soto led a live rehearsal with dancers from Ballet Taos accompanied by classical music from his friend Laura Ortman.

The evening exemplified Soto’s desire to share the rhythm and grace he cultivated during 24 years with the New York City Ballet.

“I started hoop dancing with my mother,” Soto said. “And I continued hoop dancing until I discovered ballet. And ballet was just my life. That’s all I wanted to do. My mother and father found the only local ballet school in Phoenix, Arizona, which was hours from my house. So my dad would drive there every day, and I got a full scholarship because I was the only guy in the class.”

It’s a long way from Arizona to New York City, especially for a Diné-Puerto Rican man, the son of Josephine Towne and José Soto.

“My dad loved salsa. He loved the Beach Boys, all that kind of stuff. That’s what I remember listening to. And I always got a warm feeling when I heard salsa or drums from the reservation. My heart jumps when I hear thump, thump, thump. And I always felt like, oh, God, I want to do this. I want to do this,” Soto said.

It is one of those universally acknowledged truths that anyone born in a small rural town will have to leave it to pursue their dreams — especially if they dream of classical ballet.

And so, at 13, Soto dropped out of school and left for New York. Now 60 and retired from the stage, he is committed to sharing his story across the nation’s tribal communities.

At the premiere, the rain slowed and then stopped as the celebration concluded. Soto and his husband, Luis Fuentes, were eager to return to their home in the northern New Mexico mountains. But first, they posed with friends underneath the Lensic’s marquee, which proudly announced: INT MUSEUM OF DANCE & CD: AN EVENING WITH JOCK SOTO.

“I’m liking the marquee saying my name,” Soto said.

From stage to digital cloud

Just before the premiere, I sat down with Soto in the theater lobby. While preparing for our talk, I’d practiced pronouncing his name his name correctly. I sometimes work best in binary, so I framed a reference point under the guise of the antagonists in the film Revenge of the Nerds. Soto, I thought, was not a nerd; he was a jock — the Jock.

And he is clear about who he is.

When Soto’s name was misspelled in the Navajo Times art section, he corrected it with a black Sharpie, turning the “A” into an “O.” But he kept the newspaper on the table in the lobby, relishing the sense of local pride despite the error. The article outlined how the International Museum of Dance was building a digital archive for his career, titled: “Jock Soto: The Dancer and His Life.”

It was when he finally took the stage that I realized something: Soto had sacrificed his body to dance. When he walked, he reminded me of NBA Hall of Fame greats like Bill Russell and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, who moved with pain from decades of physical achievements on the basketball court.

“It’s not an easy career at all,” Soto told the crowd, from a chair on the stage. “You know, it’s often painful. Like, I can’t even get out of this chair if I want to right now.”

“We can arrange that anytime,” Joel Aalberts, executive director at the Lensic, responded.

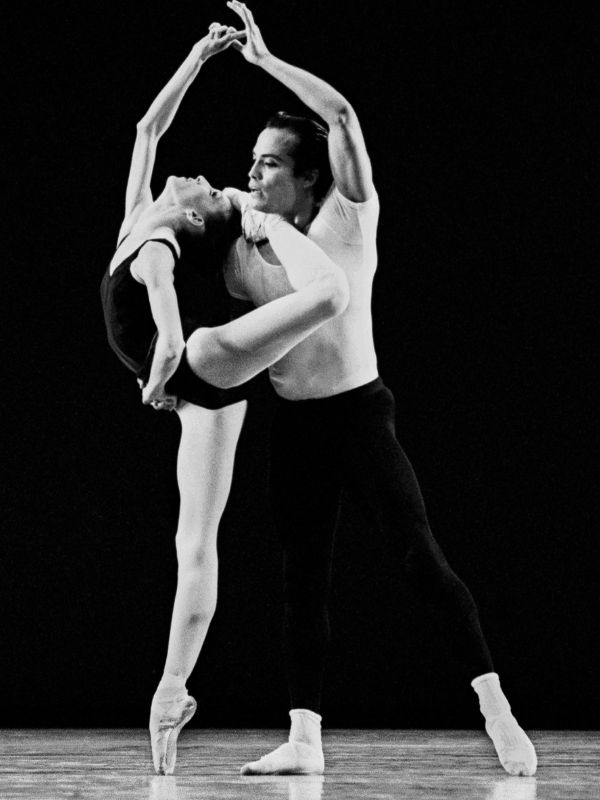

Jock Soto at 15 years old during training for “The Magic Flute.”(photo/Steven Caras)

Jock Soto at 15 years old during training for “The Magic Flute.”(photo/Steven Caras)

The obvious health impacts explain the urgency behind Soto’s desire to partner with the International Museum of Dance, sharing his lifework with the public and encouraging the next generation of dancers.

The digital archives the museum is creating preserve dance legacies and education programs. A similar project with the Dance Theater of Harlem inspired a history book about the group’s influence on Black ballet dancers.

The museum has a larger goal: creating a physical space, slated to open in 2026, to host artist residencies, performances and public events. But since a location has yet to be determined, the archives currently live in a digital cloud hosted by the nonprofit arts organization ChromaDiverse, which sifts through websites for information on the careers of dancers like Soto, unearthing forgotten photos, videos, posters, press and other ephemera.

The archive is the quickest way to immerse yourself in Soto’s life as a dancer. It also hosts the Moving Memories Fund, which established the Jock Soto Scholarship, whose first recipient is a Chickasaw dancer, Heloha Tate.

Wendy Whelan and Jock Soto in the New York City Ballet production of Agon. Choreography by George Balanchine, ©️The George Balanchine Trust. (photo/Paul Kolnik)

Wendy Whelan and Jock Soto in the New York City Ballet production of Agon. Choreography by George Balanchine, ©️The George Balanchine Trust. (photo/Paul Kolnik)

The ripple effect

Soto was only 12 when he received a full scholarship to the School of American Ballet in New York City. There, his talent blossomed among the other dancers seeking the limited roles available to men in ballet.

“I felt amazing, because (in Phoenix) I was in the class with all girls. And when I got to New York, I was in a class with all men — 40 men,” Soto said. “That was my competition, or the way that I evolved.”

At 16, he accepted an invitation from legendary choreographer George Balanchine to join the New York City Ballet. Four years later, Soto was the theater’s principal dancer — a pinnacle that any ballet dancer in the world would be delighted to reach.

“I became an adult very quickly,” Soto said. “I became very good friends with a couple of the guys. We lived in an apartment together. We had no money, but we would go buy hot dogs on the street or eat pizza and stuff like that. We lived three blocks from the school, so we spent all day till 7 every night, dancing. That’s all we did.”

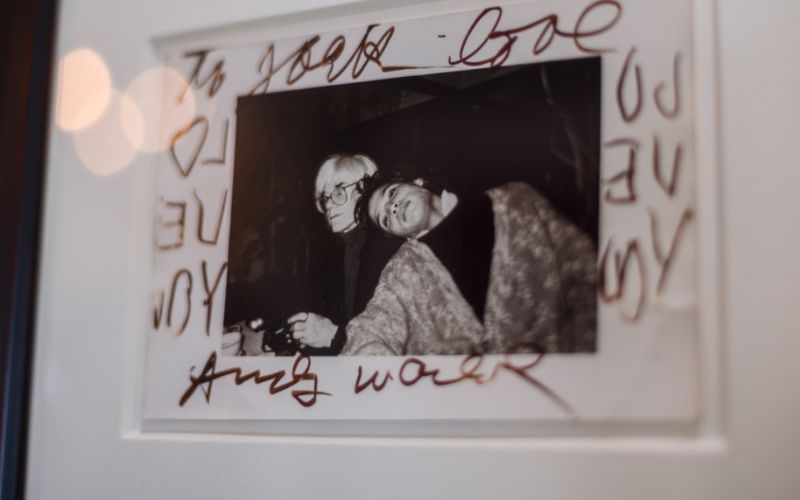

Jock Soto in a photo with Andy Warhol from his time living in New York as a young dancer. (photo/Courtesy Jock Soto)

Jock Soto in a photo with Andy Warhol from his time living in New York as a young dancer. (photo/Courtesy Jock Soto)

Soto’s finest performances occurred when he partnered with ballerinas, taking the masculine role to lift or sometimes lead the female dancer, making sure that she remained the dominant presence onstage. He became what the ballet world calls a “natural partner,” dancing as his mother had taught him to dance, as a way to gracefully walk with beauty.

Soto’s mother was his first partner in the Southwest powwow circles. She led, he followed, until he was good enough to lead; that was how he learned the significance of each dancer’s role. In ballet, he mastered the masculine role. Now, as a teacher he holds firmly to the traditional gender role necessary for successful performance.

As a teacher and openly gay man, he tells his dancers to follow traditional gender roles onstage.

“I try to teach the dancers that a man is a man onstage. And if I see anything other than that, I correct it right away. And I’m like, ‘No, no, you’re behind a ballerina, you’re a man. Don’t act like the ballerina.’ So that’s what I try to teach,” Soto said. “Masculine is masculine. It’s not that hard to teach, but it can be a lot.”

Soto’s Diné clan comes from his mother. He was born for Tó’aheedlíinii, meaning “water flowing together,” which is also the title of a 2007 documentary about Soto’s life. He was born 90 minutes away from his home in Chinle, Arizona, at the closest Indian Health Services Hospital in Gallup.

Soto said his mother was a vital inspiration.

“My mother was my strength. She was my strength, and my dad was such a macho Puerto Rican, you know,” Soto shared. “They said it was OK to be gay. And I didn’t tell them until I was 30. My mom laughed so hard on the phone. She said, ‘We’ve known that ever since you were 18.’”

More than 700 dancers are alumni of the New York City Ballet, but only several dozen men have achieved Soto’s status as a principal dancer. Elite ballet training and performance skills like his are rare. Soto has deep roots in the Navajo Nation, but his ascent to the rarefied world of ballet left him feeling distant from the Indigenous community. Today, Indigenous communities are still just getting to know Soto — something that should prompt state lawmakers and education reformers to work with local ballet theater groups to expand arts programming in Native communities and schools.

ChromaDiverse wants Soto’s digital archive to be available in New Mexico public schools within a year. Since 2018, New Mexico has invested billions in education reform as mandated by a state court order aimed at students that are Indigenous or non-English speakers or have disabilities. Making Soto’s career archive accessible excites lawmakers like Shannon Pinto, who attended Soto’s premiere, where she met him for the first time.

“We need to make sure that the arts are something we bring forward with some funding, at least, because we know it’s been on the back burner,” Pinto said.

Jock Soto has partnered with the International Museum of Dance to share his life’s work and story with the public. (Evan James Benally Atwood/High Country News)

Jock Soto has partnered with the International Museum of Dance to share his life’s work and story with the public. (Evan James Benally Atwood/High Country News)

It will take time to learn how that will affect classrooms in New Mexico and beyond. But in the broader sense, Soto’s presence has already had an impact. Jicarilla Apache President Adrian Notsinneh encountered Soto and his work for the first time at the Lensic. Onstage, as he offered a blanket gift to the dancer for his work supporting Jicarilla Apache ballet dancers, Notsinneh told the audience how Soto led him to reflect on skipping flat stones across water as a child.

“As it jumps across, it causes ripples. Each time it hits the surface, it radiates. So what I’m seeing from this type of person that’s standing here with me is a type of person that causes that ripple effect,” Notsinneh said, standing next to Soto. “Within his lifetime, he’s caused so much of this effect. And I want to thank you for being that type of person.”

The ripple effect was shown in the crowd’s response to the evening.

As Santa Fe calligraphy artist Blythe Mariano (Diné) put it: “To know that somebody from where I’m from made it all the way to New York is like, oh my God, I’m getting overwhelmed,” she said. The artist, who is from Church Rock, New Mexico, was born in Gallup at the same hospital as Soto.

At the end of the night, when I asked Soto if he had noticed the large number of young Indigenous people in the audience, he beamed with excitement.

“I loved it, I loved it. It’s inspiring!” Soto radiated the enthusiasm he felt. “Like I said onstage: You have to be inspired.”

More Stories Like This

Two Indigenous Group Exhibits Opening January 9, 2026 at WatermarkWatermark Art Center to Host “Minwaajimowinan — Good Stories” Exhibition

Museums Alaska Awards More Than $200,000 to 12 Cultural Organizations Statewide

Zuni Youth Enrichment Project Takes Top Emerging Artist Apprentices to Phoenix for Artistic Exploration and Cultural Immersion

From Dishwasher to Award-Winning Chef: Laguna Pueblo's Josh Aragon Serves Up Albuquerque's Best Green Chile Stew

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher