- Details

- By Rima Krisst - Navajo Times

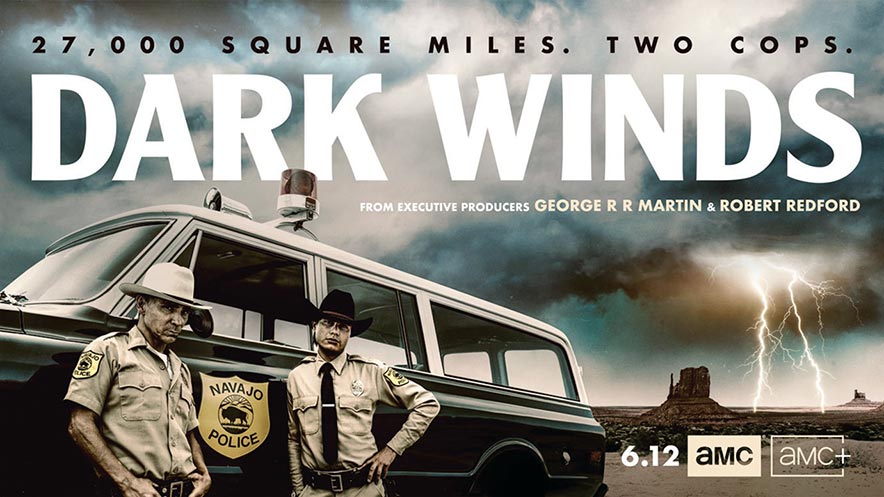

WINDOW ROCK-Despite fine acting, suspense and entertainment featured in the first episodes of the AMC mystery series “Dark Winds,” overall the show misses the mark when it comes to accurately portraying Navajo language and culture, say some Diné experts.

While the creators promote the mystery thriller as authentic Native American storytelling by Native Americans, the distinction between what is “Native” and what is Diné quickly becomes blurred.

“People just assume that we’re Indigenous and we’re all alike,” said Diné language and literacy educator Clarissa Yazzie. “The Indigenous community is so diverse. You can’t just clump us into one stereotype. We’re not one culture.”

Set in 1971 on the Navajo Nation and based on Tony Hillerman’s “Listening Woman,” “Dark Winds” kicks off its first episode, “Monster Slayer,” with a dramatic helicopter bank heist in Gallup.

A gruesome hotel double-murder follows and viewers are introduced to the three lead characters tasked with solving the crimes.

The show follows veteran actor Zahn McClarnon, Lakota, as police Lt. Joe Leaphorn, Jessica Matten, Red-River Metis Cree, as Sgt. Bernadette Manuelito and Kiowa Gordon, Hualapai, as Deputy Jim Chee.

The investigation leads them to confront evil forces, past traumas and supernatural events that portend a possible link between the two cases.

No excuses

One thing learned in the first episode is that if a non-Diné actor wants to depict a Navajo character, they need to have Navajo language lines down and support to do that.

“C’mon Hollywood, do better,” said Clarissa Yazzie, who is also a popular social media influencer.

In a TikTok critique, Yazzie spelled out how some of the actors’ mispronunciation of words changed their meaning to the point of distraction and shock.

“As far as dialect coaches, there are so many Navajo speaking professionals that they could have reached out to who could have helped with the Navajo speaking roles,” said Yazzie. “They really dropped the ball on that part.”

Any number of people would have caught the mistakes and possibly recovered the good parts of the whole thing, she said.

“I actually didn’t finish the first episode for that reason,” she said. “It’s just too distracting. As an advocate for Diné language revitalization, for me this is just a big ‘no.’”

While some people are making excuses for the misrepresentation, Yazzie said she can’t accept that either.

“I really think there should be no excuse,” she said. “If you’re going to produce a show based around the Navajo culture, the Navajo people, the Navajo Reservation, and you’re going to be using the Navajo language that much, I think they should have done more than they did.

“It can’t just be an afterthought,” she said.

She said if Hollywood is making a film about a specific Indigenous community, such as Diné for “Dark Winds,” then they should do everything that they can to connect with the right people to ensure accuracy for the roles, language and cultural aspects.

“If you’re trying to do it justice, give us the respect that we need, that we deserve, especially when Hollywood is trying to work on making things right,” she said. “This really isn’t going down the right path for us.”

Yazzie also said, as partially revealed through the language, the lead characters don’t come across as authentically Navajo.

“This is feeding into that stereotype that all Indigenous people are the same when we are not,” said Yazzie.

“Hollywood is trying to make money,” she said. “They’re trying to target a certain audience so they’re going to try to cast people who are already well-known. That has a lot to do with who was cast for these roles.”

She said the production company should have met the non-Diné actors halfway like Zahn McClarnon by giving them the support they needed to execute the language more proficiently.

“I’m putting that on the production team,” she said. “We aren’t expecting them to be 100 percent fluent, but learn a handful of lines.”

This is not about bashing the actors, said Yazzie.

“I love Zahn,” she said. “He’s a great actor.

“There are two ways they could have gone about this – they could have cast Diné speaking actors – I know there were a few who auditioned for these lead roles,” said Yazzie. “Or, hire dialect coaches to help with the pronunciation and fluency.”

However, Yazzie said, unfortunately, while there is plenty of Diné talent out there, that’s not necessarily what Hollywood looks for.

“If they don’t fit the physical description of Hollywood’s image they won’t get cast,” she said. “We have to look a certain way to land these roles.”

‘Hollywood mentality’

Long time Diné language and culture teacher Albert Brent Chase also said while he thought the acting in the film was good, when it came to the language, he had a hard time understanding.

“The pronunciation wasn’t on point,” said Chase. “As a fluent speaker, I was kind of listening harder to understand. Good thing they had captions, because otherwise I wouldn’t have gotten the gist of what they were saying.”

He said the mistakes are so jarring that they take away from the story and the entertainment.

“From there it just went downhill, because I was distraught in trying to understand my own language in the movie,” he said. “It kind of ruins the enjoyment of a TV show and you start thinking, where were the consultants?”

Chase said the whole thing made him wonder if the actors were coached by someone who was fluent in Navajo.

“Or was there enough time given to the actors so they could get it right?” he said. “It’s a good try on their part. It’s not their fault because they’re not Navajo, which is also puzzling, because why can’t they just use Navajos?”

He feels not enough care was put into the production which would have made it more exciting and more authentic.

“The film industry, they want Native Americans, but they don’t care enough yet to get it right,” he said. “You know the industry’s not going to listen to us. It’s just like the John Wayne days. They screwed it up from the beginning and they’re still doing it today.”

Chase said the film industry should know that there are still fluent speakers left who could consult with filmmakers.

“We’re here,” said Chase.

“Film crews should really just ask and dig deeper into the investigation of who could be very helpful for them,” he said. “I would have not even allowed them to film that until I had those people who are speaking get it right, or stop, cut, and do it again.”

While Chase said he finds it insulting that the language wasn’t right, there were other things that were said or shown that were inappropriate to the Navajo culture, including how a burial was portrayed and the handling of sacred items.

“I thought, that’s kind of demeaning to our people,” he said. “There are cultural aspects that were almost a little condescending for us traditional people. We know that’s not what it is and how it is and they need to not do that.”

Chase also said certain décor like the Pueblo revival style trading post with decorative red chile ristras featured in the series are inappropriate.

“That’s traditionally Pueblo,” said Chase. “If we do have it, it’s not usually decorating our place.”

Due to COVID-19 restrictions on the Navajo Nation, “Dark Winds” was filmed mostly on Tesuque and Cochiti puebloa, not on Dinétah.

Chase also said, while they might be entertaining, the Leaphorn and Chee characters do not ring true as authentically Navajo.

“You’ve got to live the culture, you’ve got to be the culture in order to personify that,” he said. “They probably just went through the list to see who is Native American and plopped them in. That’s the Hollywood mentality.”

‘Tourist gaze’

Diné author, historian and chairwoman of the Navajo Nation Human Rights Commission Jennifer Denetdale said the production is so off track in terms of representing Diné life that it’s more like a comedy or spoof.

Therefore, having a conversation about “accuracy and authenticity” simply does not fit when it comes to “Dark Winds,” she said.

Denetdate said Tony Hillerman’s stories are depictions of what white people think about the West and “Indians,” signifying something ‘bizarre, exotic” that’s different from where they come from, she said.

“It’s Hollywood culture,” said Denetdale. “When you’re starting with Tony Hillerman, you can’t make a leap to accuracy or authenticity. When you’re starting with Tony Hillerman, you’re not even in the framework.”

Denetdale is also an Indigenous film teacher at the University of New Mexico and said the “Dark Winds” reviews she’s seen don’t even consider the “butchering” of the language.

“The thing that was just hilarious to me in talking to other Navajo people is that most of it is indecipherable,” she said. “I have no idea what they’re saying. It doesn’t make any sense.”

She said while some films might offer some good exposure to the Navajo language, this is not one of them.

“I think Navajo people who speak Navajo think it’s a caricature,” said Dinetdale. “I just laugh at it. I’m like, I’m sure they’re speaking Cherokee.”

She noted the fish in the Navajo translation of “Finding Nemo” spoke better Navajo than the non-Diné cast of “Dark Winds.”

Denetdale said there are also so many accomplished Diné filmmakers who could have advised the producers.

“They didn’t have any sensibility to invite any of these filmmakers to be part of their production,” she said.

Furthermore, the fascination with Navajo people, witchery and skinwalkers panders to white people’s expectations and their thirst or interest in the bizarre, said Denetdate.

“We don’t talk about witchery,” said Denetdale. “In this movie, it just becomes something silly.

“If you have those conversations, they’re in your intimate circle,” she said. “It just a real lack of sensitivity, a real lack of seeking to understand your Navajos, when you’re just interested in making them weird.”

She said nuances like people milling around hogans wearing turquoise jewelry was like a “signifier” of being Navajo, but isn’t something that would normally happen in real life.

“It’s like one of those dioramas you used to see in the museums of Native life, she said. “It’s like a living diorama.”

In that way, “Dark Winds” is just a perpetuation of the Western genre, she said.

“It’s like a tourist gaze, coming out of Santa Fe,” she said. “One of thing that was authentic about the film was the flies.”

However, Denetdale said this doesn’t take away from some of the great acting in the show, including by Zahn McClarnon.

“He’s great,” she said. “I just consider it entertainment. I never see anything that starts with representation as progress. It’s a comedy. The acting is really good. I think the actors have done a good job.”

‘Misconceptions’

Yazzie agreed the portrayal of witches and Navajo spirituality as “dark or evil” in “Dark Winds” comes back to the mis-portrayal of the culture.

“Non-Natives focus so much on the bad stuff, the mystery, so now people are going to ask, are there really witches on the reservation?” she said.

These negative portrayals and stereotypes shift the focus away from the beauty of Navajo culture.

“That’s the sad part of it for me,” she said.

While some Diné have said this is a “white story” made for a white audience and there’s nothing you can really do to change that, Yazzie said she can’t accept that either.

“Now we’re going to have all these misconceptions of the Diné culture and the Diné language,” she said. “All these years and decades we’ve been asking for correct representation and now we have the opportunity to reach millions of people and it’s all done incorrectly.”

She hopes if there’s a second season and the “Dark Winds” producers take action to do right by the Navajo people.

“It’s like taking two steps forward and three steps back all over again,” she said.

Next in the series: An exclusive interview with Chris Eyre, Cheyenne/Arapaho, director of “Dark Winds” as well as Diné consultants, actors and writers on the show.

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher