- Details

- By Jenna Kunze

New York State is second only to Texas in its failure to collect and analyze COVID-19 data from American Indian and Alaska Native populations, according to a Urban Indian Health Institute (UIHI) study.

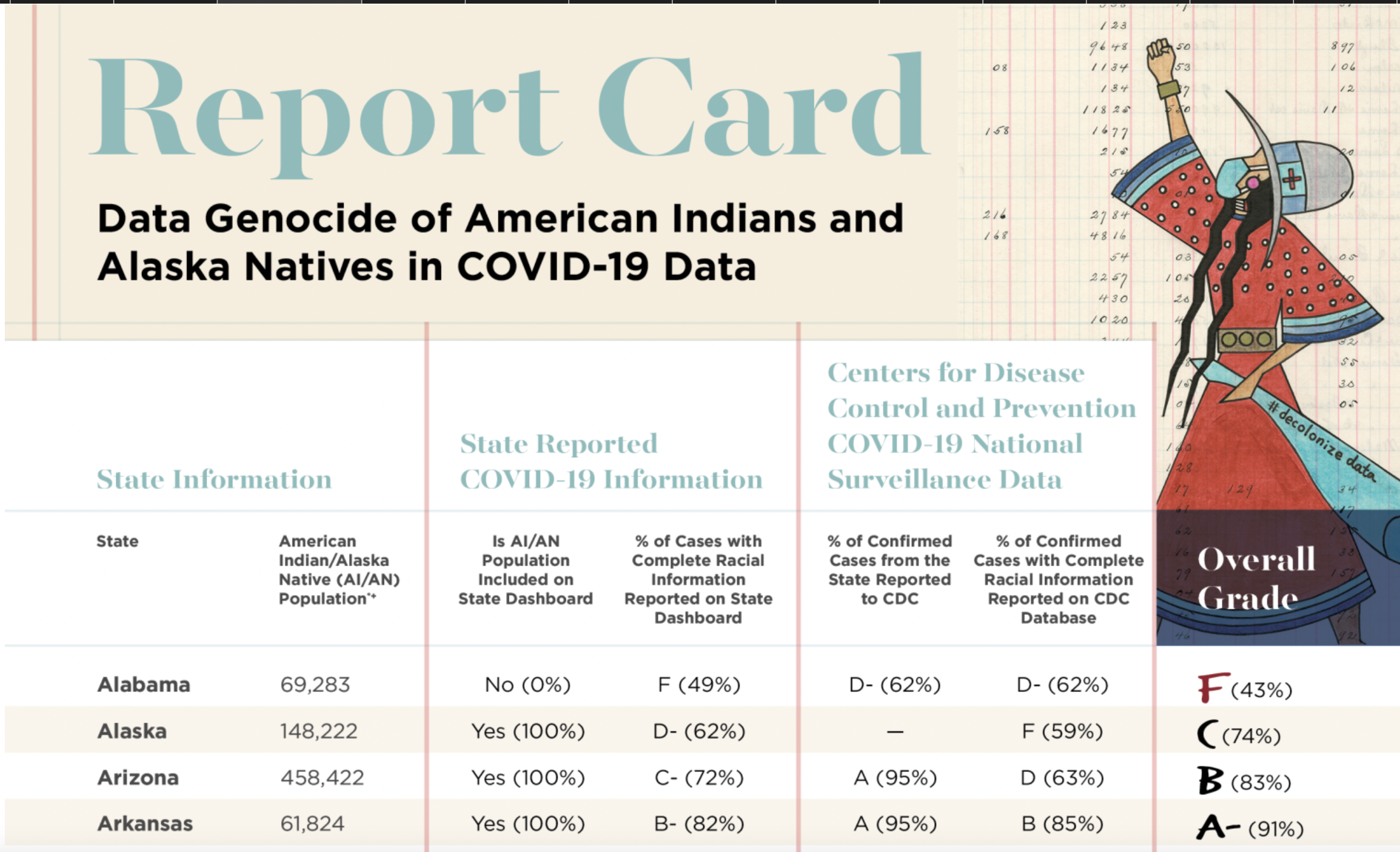

Published in February, the study ranked states based on their quality of COVID-19 racial data and their effectiveness in collecting and reporting data on Native populations. Texas got a grade of 20 percent, and New York 27 percent.

New York is among 16 states that fail to report data on COVID-19 among American Indians and Alaska Native people as a distinct demographic category. Rather, they lumped them in as “other.” It was the only state that did not list complete racial information for any of the cases reported.

In the first phase of the epidemic, American Indian and Alaska Natives had a mortality rate from COVID-19 1.8 times higher than that of non-Hispanic whites, according to a CDC report looking at data from 14 states.

The UIHI study gave Minnesota the best grade, 93 percent. Arkansas, which ranks near the bottom on many public-health indices, fared among the best states in the U.S. at tracking data on COVID-19 among Native people and reporting it to the federal Centers for Disease Control. It tied with Maine for the second-highest ranking.

UIHI is a Seattle-based research and epidemiology center that says its mission is “decolonizing data” for Indigenous people, by Indigenous people.

Both New York State and New York City group American Indians and Alaska Natives in the “other” category of racial data. Yet the New York City metropolitan area (which includes Long Island and much of New Jersey) had the fifth highest population of urban American Indians and Alaska Natives in the nation, with 50,000, according to a 2013 Census Bureau estimate.

“It doesn’t surprise me,” said Lance Gumbs, who formerly served as tribal chairman and now serves as the tribal ambassador of the Shinnecock Nation on Long Island, the closest federally recognized tribe to New York City. According to Gumbs, during the height of the pandemic in 2020, state health officials weren’t reporting the true total of Shinnecock citizens who’d tested positive for COVID-19, because they weren’t combining the number of cases among Shinnecocks who’d gotten tested off the reservation with that of tribal citizens who tested positive on the reservation. That lack of information contributed to the virus spreading rapidly in multigenerational homes, and a lack of awareness among tribal members about its true severity.

“It led to additional cases that, quite frankly, could have been prevented,” Gumbs said.

The UIHI study ranked states based on four criteria: whether Natives were included as a distinct category in the state health department’s data; the percentage of cases with complete racial information reported in state’s data; the percentage of confirmed cases from the state reported to the CDC; and the percentage of confirmed cases with complete racial information reported in the CDC database.

Despite the Empire State’s eight federally recognized tribes and official population of 318,858 Natives (according to state data listed in the report), the New York Department of Health does not include any data specific to Natives in its reporting.

The Urban Indian Health Institute is the main tribal epidemiology center tracking public health for Native Americans who live off reservations. Its director, Abigail Echo Hawk (Pawnee), calls the UIHI findings an indication of “data genocide.”

The CDC initially denied Echo Hawk and UIHI’s request for raw COVID-19 data, the same information made freely available to states. It took a year and two congressional hearings before the CDC agreed to hand the data over, she said.

“I see the elimination of American Indians and Alaska Native people as the present-day way that the United States government, states, and counties are perpetuating genocide of our people,” Echo Hawk, an epidemiologist and health equity expert, told Native News Online. “By eliminating us, they're effectively saying we don't exist. And with that comes the non-fulfillment of treaty and trust responsibility.”

When information isn’t collected or reported correctly, she said, it translates to a loss of financial resources, political resources, and life.

“More people got COVID as a result of that,” she said. “More people died.”

That motivated Echo Hawk and her team to develop the UIHI report card to make sense of the little data the CDC kept on Native American and Alaska Natives affected by COVID-19. The study also provides a tool guide for states to improve their reporting, which Echo Hawk said Oregon is beginning to implement.

The New York State Department of Health did not respond to multiple requests for comment from Native News Online. Health officials in Maryland, the third poorest-scoring state after Texas and New York, said they didn’t collect specific data on American Indians and Alaska Natives “due to low statistical occurrences given the population of Native Americans in the state.”

“Race and ethnicity are self-reported, and data from respondents that do not fall into the listed categories are reported under the ‘other’ category,” Maryland Department of Health spokesperson Andy Cohen wrote to Native News Online.

Echo Hawk calls that lazy epidemiology.

“My answer to that is: why is our population small? Because of genocide,” she said. “And now they are part of perpetuating that through a data genocide. And so they have become not only complicit, they have become participants.”

Racism as a public-health crisis

On Oct. 19, the New York City Board of Health declared racism a public-health crisis, passing a resolution that asks the city Health Department to establish a Data for Equity working group to ensure that it applies an “anti-racism equity lens” to public-health data, and to collaborate with other agencies “to report on fatalities, injuries, health conditions, by race, gender, and other demographics, to improve data quality and care.”

Commissioners at the Oct. 19 meeting said they specifically chose “resolution” over “declaration,” to spur action beyond mere recognition of the problem.

Gumbs said that he hopes the resolution will bring about better representation and education for New York City and beyond.

“It has to be a statewide outreach to the tribal communities...in order to receive adequate funding and adequate information,” he said. “There has to be an awareness of all of the groups that make up New York State--not just the tribal groups, but in the city's urban Indian populations.”

That, he added, calls for “better outreach and coordination” and a “coordinated effort on behalf of the state.”

Echo Hawk is chair of an equity commission in Washington state’s King County, which includes Seattle. In June 2020, it declared racism a public health crisis and allocated $25 million for the pandemic-related economic recovery of Black and Indigenous communities.

“Unless these proclamations actually have an allocation of resources [and] accountability to the communities which they're saying they're wanting to serve, they’re meaningless,” she said. “You can say all you want. Where's the action?”

More Stories Like This

$1.25 Million Grant Gives Hope to Tolowa Dee-ni' Nation Amid Housing CrisisHHS Repeals Nursing Home Staffing Requirements, Citing Relief for Tribal Facilities

Native Americans Face Second-Highest Gun Death Rate in U.S., New Study Shows

National Council of Urban Indian Health Encourages Vaccinations

New Native Nations Center for Tribal Policy Research Analyst Will Examine Cancer Disparities in Oklahoma Tribes