- Details

- By Native News Online Staff

In light of the fifth annual Native Nutrition Conference convening this week in Prior Lake, Minnesota, Native News Online spoke with Michael Yellow Bird, the dean and the professor of the Faculty of Social Work at the University of Manitoba, Winnipeg. Yellow Bird is a citizen of the three affiliated tribes, the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara in North Dakota.

This interview has been edited for content and clarity.

Native News Online: Can you tell us what you'll be speaking about at the conference?

Yellow Bird: I'm going to be talking about the importance of fasting and its connection to improving Indigenous health and wellness. It's been something I've been doing for many years, and it's something I've developed a bit of scholarship around, writing about it and studying it for a while now.

Native News Online: What is the benefit of fasting?

Yellow Bird: What I found is that fasting really is a part of our human evolution. For millions of years, our ancestors evolved during times of famine and during times of a lot of food, and climate change really played a major role in what foods were available to us, for many, many years. So, it's the idea that, before the advent of agriculture, about 12,000 years ago or so, our ancestors lived a lot on wild plants, fruits, grasses, seeds, things like nuts and fish and other animals. These were the nutritional pillars of our human diet. But of course, when the seasons changed and things got scarce, we needed to save energy to go out and hunt and gather foods, so we wouldn't starve. We all ate very sparingly for days or weeks and months, sometimes went without eating. People talk about food insecurity. Insecurity was really a huge part of our evolution–-food availability was hit and miss, really.

What science or Western times now calls calorie restriction–when people intentionally abstain from eating too much. It’s pretty clear that this is what most populations did. They only ate when they were truly hungry, especially when they were going through these periods where there was a flatline in the amount of food that was available. So, because of that, we developed particular kinds of genetic profiles that were passed down from generation after generation and epigenetically.

For example, when we are living in the Western world, where all this food is available, and we have all these calories, one of the things that some of us do is we eat more than we probably should in this society, because we have this capacity to put on weight for the next starvation period that comes around. And this is why some of us are around here today: our ancestors developed that capacity to what we'd call overeating today and store a lot of fat so that they survive the next famine, and so on. And today, we have this, what they call ad libitum eating. And for us, it's like eating so many meals every day, and so many snacks every day, and of course, we end up with things like diabetes and obesity, all these different kinds of chronic diseases and metabolic disorders where we have a lot of visceral fat, we end up with tumors and cancers and Alzheimer's disease, dementia, those kinds of things.

As people, especially as Indigenous people, we carry that ability to acquire a lot of weight and fat, and move as little as possible for the next starvation period right. Now, in this world today, as I said, we don't have that problem. That's why fasting today is one of those mechanisms that helps to moderate the food and it helps to prevent the diseases of what they call civilization: Coronary heart disease, obesity, hypertension, diabetes, type two diabetes, all those different kinds of things. We know that these diseases are rare among hunter gatherers and non-westernized populations, because they still live a lot like our ancestors did.

And our bodies really struggle to stay healthy in these modern times, because of all this food availability and our lack of movement, or lack of fasting and so on.

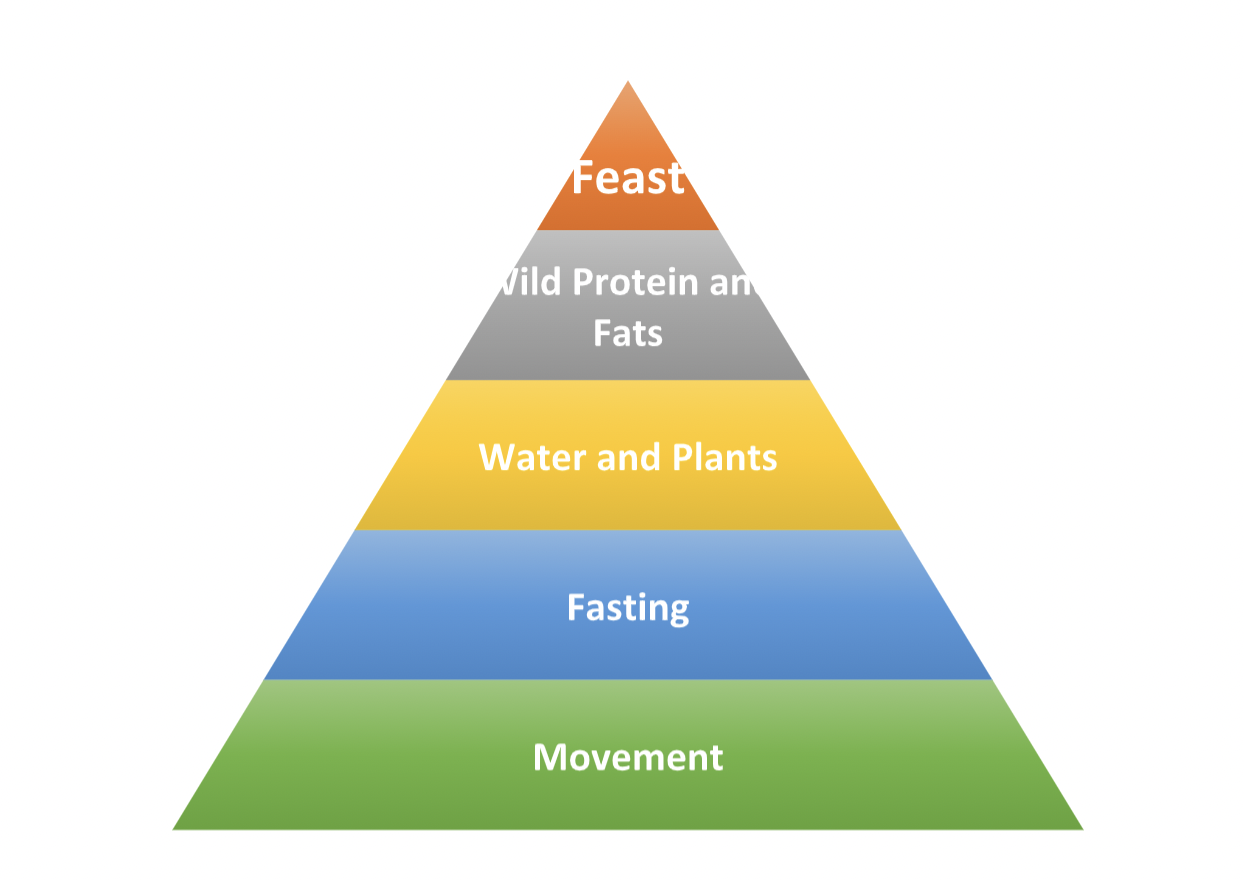

While most people at the conference are going to be talking about nutrition and eating traditional foods, I'm going to be talking about decolonizing your need to feed.

How does one decolonize the need to feed?

Yellow Bird: I tell people, I don't give medical advice or anything, but it's my own experience that the first thing a person has to know is their genetics in terms of their nutrigenomics, what kinds of foods can you eat? And what does it mean to your health and your well being when you eat certain kinds of foods?

Sometimes a doctor can tell you to eat this or a nutritionist can tell you to eat that, but I don't really put a lot of stock in that unless you have genetic data of what your diet type looks like, whether or not you’re the kind of person that can eat carbs.

For example, I don't have a problem eating carbs because I have particular genes that help clear the carbohydrates out so I don't have diabetes. Now I'm the kind of person that has copies of risk mutations for fat, that I have to really watch out for if I eat steaks and things like that, I’ll have a heart attack and I'll have a stroke just because I don't have the genetics to clear it.

So my Indigenous roots probably go way back someplace into the deserts of Mexico as I see that and probably for thousands of years. My people are plant-based eaters for a long period of time and meat was kind of just a side dish. In most cases, I think that's how most people are.

But the flip side is we've been eating a lot of carbohydrates and that is one of the things that drives our, our inability to fast.

Can you tell us how one would find their nutrigenetics?

Yellow Bird: First it's really important to get a nutrigenomics test done. I use one provider called GeneFood. What they do is they give you kind of a profile of your genetic, you know, your blueprint, and then it tells you a bit about what kinds of genes you have their risk genes, what kinds of genes that are genes that can break down bread and those kinds of like white rice and those kinds of things. There's a lot of people that can eat meat but they may or may not realize that they have the genes to clear the cholesterol in the saturated fat of the blood system.

Another thing that people do is they do a different kind of analysis, a human microbiome analysis. And you'll find out whether or not you've got the bacteria in your gut that's breaking down different kinds of foods -- proteins and carbohydrates and macro and micro nutrients in the body.

It's not just not just the genetics, but it's also what you're feeding yourself and kind of how your levels your gut health is and based upon the different species of bacteria you have in your gut that are breaking down these different kinds of foods.

Do you have any other insights that you want to share with people?

Yellow Bird: One of the things that I found out that was really important for me was was understanding how my genetics was related to my health and I think that's the key thing–not do a lot of guesswork or depend on your doctor's recommendation, because a lot of times, doctors you know, your regular GP will give you average-person kind of information, when in fact you may be a person that is that's not an average kind of person. So what I mean by that is that, you know, you could inherit genes from your parents that put you at risk for certain health conditions.

Genes are not destiny, but it's like I'll say at the conference, genes are the loaded gun. Our lifestyles can pull the trigger, to put us in this place where we end up with some kind of disease or whatever.

When you think about lifestyle, think about who we've been as Indigenous people for thousands or hundreds of thousands of years. And of course, you know, what we did is we ate pretty much a plant based diet with a lot of fiber, meat, proteins, and those kinds of things were a side dish, but for most people, other people can eat higher levels of those kinds of things. But you know, on the safe side, that's where you'd be.

When you think about the importance of fasting, people think about it as ceremonial but to me, it's like an everyday kind of thing that you know we need to do, and something I do every day so I encourage people to do that.

To fast and to check in with a knowledgeable health care provider. Most primary care physicians don't have a clue about what it means or how to deal with it, but you can find some really thoughtful health care providers and talk to them about that. And even people who have diabetes can fast if it's done in the right way. For me, intermittent fasting is not like starving yourself. It's just changing the timing of your eating. I fast for 18 hours a day. Six hours a day, I eat. I eat my first meal at about 11 o'clock and leave my last meal at about five o'clock and I won't eat again until the next day till 11 o'clock, in between all of that I’m working and running, lifting weights, walking and being very busy. So I've been doing it for such a long time, my blood pressure's good, my glucose levels are perfect.

And as we get older, we need all the help we can to stay healthy and what we know from a lot of studies is that prolonged fasting protects the immune system, protects our brain, protects our body in so many different kinds of ways.

When looking for nutrigenomics or human biome providers, Yellow Bird recommends researching the provider and learning how they protect and store your information, and look for providers with good reputation.

More Stories Like This

Language is Medicine: Navajo Researcher Tackles Speech Delays in Native Communities"Artificial Intelligence Impacts the Art and Science of Dentistry - Part 1

Chumash Tribe’s Project Pink Raises $10,083 for Goleta Valley Cottage Hospital Breast Imaging Center

My Favorite Stories of 2025

The blueprint for Indigenous Food Sovereignty is Served at Owamni