- Details

- By Stephen Carr Hampton

GUEST OPINION.

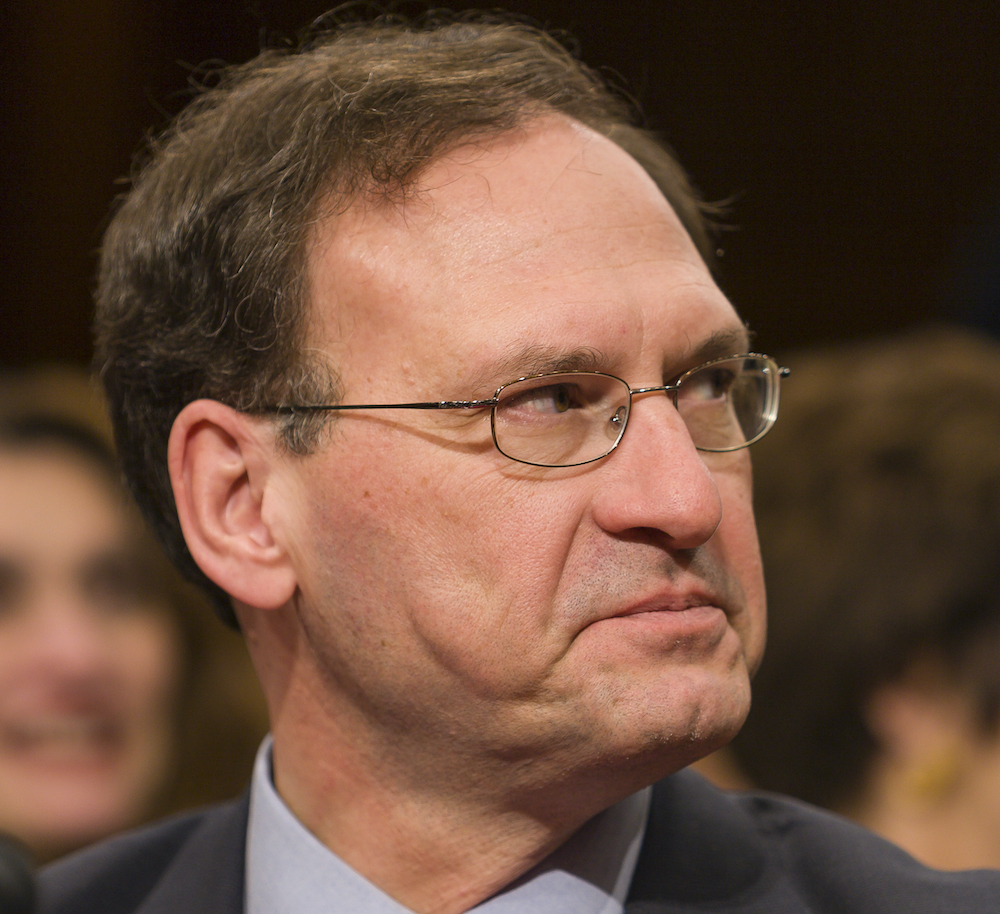

Dear Justice Alito,

Like many Indigenous people in the United States, I watched the Supreme Court hearings on Brackeen v. Haaland live last November. This case essentially puts the federal Indian Child Welfare Act on trial.

During the hearing, you questioned the rationale behind the law’s “third tier” preference, which says that, if no extended family member can be found (the first tier), and no foster family from the same tribe can be found (the second tier), children in need of foster care should be awarded, if possible, to a foster family from another federally recognized tribe.

You asked, “but why -- why is it rational [to foster a child in the home of someone from another tribe]? Before the arrival of Europeans, the tribes were at war with each other often, and they were separated by an entire continent. And I -- I don't know how many cultural similarities you would identify if you compared a tribe in Florida with a tribe in Alaska.”

Under the law, we are your people, your constituents, just as much as the Brackeens are. It seems that you can imagine the Brackeens’ lives and struggles, but not so much ours. Let me help you.

Let’s begin by unpacking your question.

First, the tribes were not “at war with each other often.” We should start with the word “war,” which was understood much differently in North America than in Europe. The majority of conflicts between Native American tribes were tit-for-tat killings and kidnappings of a few people. This followed a certain “mourning war” etiquette, with revenge carried out by the aggrieved family or clan. You might be thinking of Europe, where wars even in the 1600s killed hundreds of thousands of people.

Yes, there were rivalries and conflicts among Native Americans, but there were also vast confederations and alliances. The Comanche and Ute and Shoshone are connected, as are the Creek (Muskogee) and Seminole. The Ojibwe, Potawatomi, and Odawa are the Anishinaabeg. They have a history of partnership with the Ojibwe, Ho-Chunk, Miami, Lenape, and Shawnee. The Seneca, Cayuga, Onondaga, Oneida, and Mohawk are the Iroquois (Haudenosaunee) Confederacy—the Five Nations. Later, when the English drove them out, they took in their relatives, the Tuscarora, and became the Six Nations. The Cheyenne, Arapaho, and Lakota Sioux often camped together. Intermarriages between these allies are widely known, both historically and now.

Today, not only are mixed inter-tribal families common, but many reservations are also mixed, having been created as concentration camps holding multiple tribes. Today it is this mixture, not the tribe, that is typically the federally recognized entity. Take, for example, the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation in eastern Washington, a federally recognized “tribe” that includes 12 distinct tribes. Other tribes are split across several reservations, each their own legal entity. Lakota can be found at Pine Ridge, Rosebud, and Standing Rock in South and North Dakota, among others. Even the small S’Klallam tribe is spread across three reservations on Washington’s Olympic Peninsula, each their own separate federally recognized tribe.

Furthermore, there is now a robust pan-tribal culture. Unity across Indian Country really started during the incarceration era, because we were all thrown together and had a common enemy: the United States. My own family is Cherokee, but one of my great-grandmas, born in Indian Territory just after the Trail of Tears, married a Choctaw man in the early 1880s. As early as 1889, the Ghost Dance movement, a spiritual revival, started among the Northern Paiute and spread to reservations across the West. Today, members of hundreds of tribes participate together in powwows, large cultural gatherings, each year. We meet each other, we marry each other, and we have kids together, creating a pan-Indian culture. This has been going on for centuries, but especially in the last 100 years.

It is not just marriages and culture and dances that unite us. When the Dakota Access Pipeline was rerouted from Bismarck, North Dakota to Standing Rock and approved without consulting the affected tribes or even an environmental-impact statement, more than 5,000 people from more than 100 tribes went to Standing Rock to support the water protectors. This may have been the largest single political protest by Indigenous Americans in history.

Perhaps our single most unifying factor is dealing with the federal government. This especially includes the Supreme Court. If there’s one document that unifies us, that puts all tribes in the same boat, that confines us to similar experiences in the modern world, it’s the Constitution of the United States. It treats us as “the Indian tribes” and thus confines us to a maze of contradictory court rulings, most often decided by people like you with a remarkable ignorance of our realities.

So back to your question, what are the similarities among tribes across the country? I can list genocide, ethnic cleansing, internment, boarding schools, discrimination, forced sterilization, resource exploitation, poverty, diabetes, suicide, and child removal—which is what the Indian Child Welfare Act addressed.

I can also list resilience, determination, family connections, love, and laughter. And powwows, frybread, the three sisters (corn, beans, and squash), the television series Reservation Dogs, actual rez dogs, and navigating the Indian Health Service. All tribes are unique, but we are connected – culturally, experientially, and legally.

My point is simply that tribes – and Native families – across the nation have a lot more in common with each other than they do with non-tribal families.

Congress recognized this. It created the Indian Child Welfare Act to address a problem. That problem was that a third of Native children had been removed from their parents and given to non-Native parents. This closely fit subpart E of the Geneva Convention definition of genocide: that genocide includes “forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.”

The Indian Child Welfare Act worked – and it would work better if it were fully enforced. There are still social workers, adoption agencies, lawyers, and judges who deliberately violate it. That’s who you should be going after.

Please, do some site visits. Check out Colville, Chinle, Tahlequah, Red Lake, or Cannon Ball. Better yet, go to a powwow.

Then answer your own question.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Stephen Carr Hampton is an enrolled citizen of Cherokee Nation. He lives in Port Townsend, Washington, where he is an active member of the Cherokee Community of Puget Sound. He is the author of the Memories of the People blog, which has followed the recent ICWA cases closely.

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher