- Details

- By Braela Kwan, Crosscut

Mike McKenzie felt that he had to leave his home. He says he was no longer welcome in Skeetchestn, a community in central British Columbia west of Kamloops that’s one of 17 reserves in the Secwepemc Nation. Three years later, he’s still not home.

His uprooting was by choice, but not by preference. McKenzie said he felt compelled to leave because of tensions around his outspoken opposition to the Trans Mountain Expansion Project, which is building a second pipeline to pump heavy oil from Alberta’s tar sands to a tanker terminal near Vancouver.

[This story was originally published by Crosscut. Crosscut is a service of Cascade Public Media, a nonprofit, public media organization. Visit crosscut.com/membership to support independent journalism.]

Opposition comes with conflict since the project has also amassed considerable support within the Secwepemc Nation. Some elected chiefs representing Secwepemc reserves say its environmental risks are manageable, and four signed long-term agreements for shared benefits between their communities and the pipeline. Meanwhile, some of the more traditional leaders within First Nations are opposed.

“I'm not living in my nation right now. And I can't live in my nation right now,” said McKenzie. He stays away, he says, because he feels unsafe there — that he is targeted and harassed by local police.

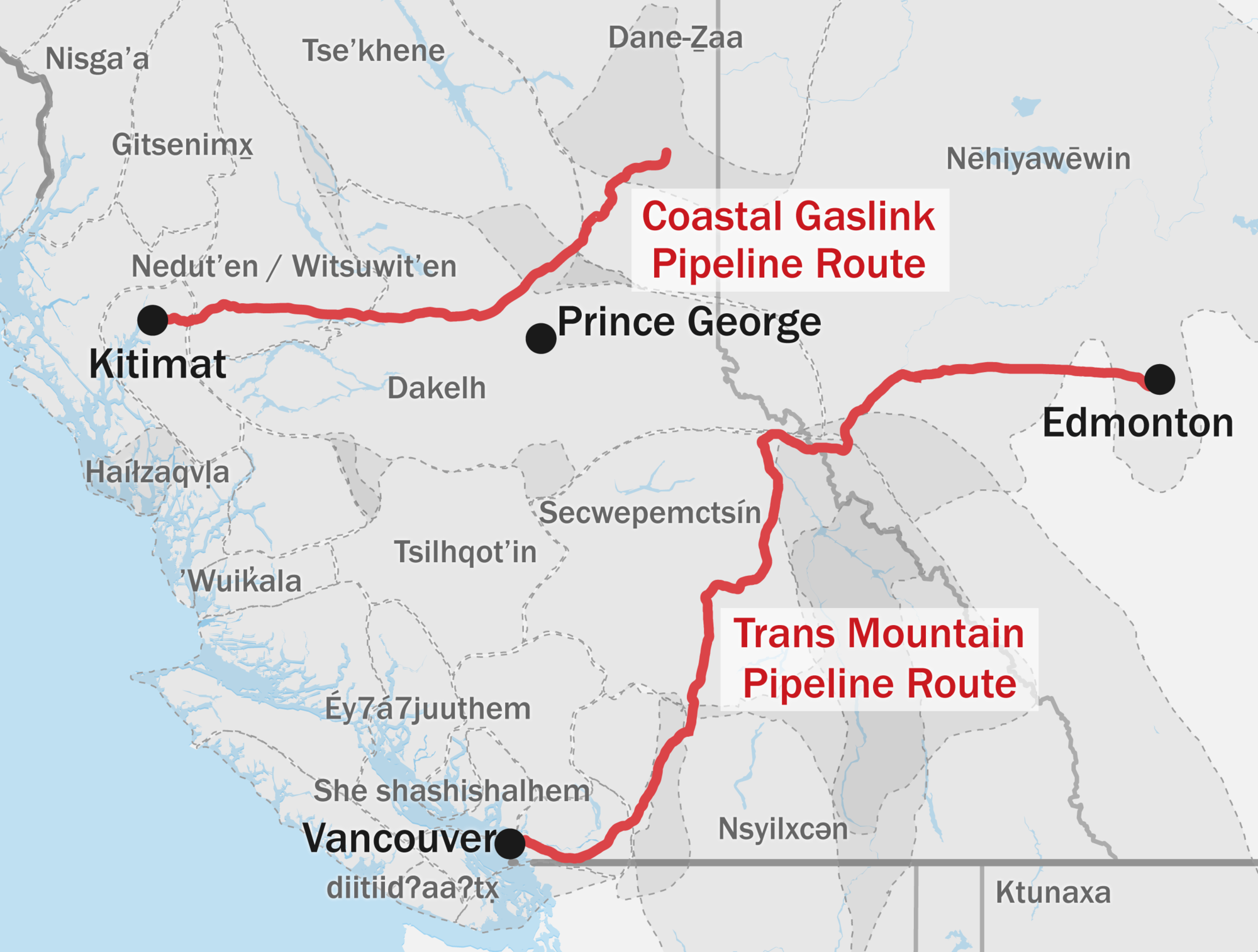

McKenzie and other Indigenous opponents of the Trans Mountain pipeline comprise the vanguard of a network of eco-activists, local governments, economists and lawyers fighting new pipeline infrastructure under construction in British Columbia. Opponents decry how two new pipelines — the Trans Mountain expansion and a natural gas pipeline farther north, Coastal GasLink — will lock in decades of dangerous greenhouse gas emissions and, they say, compromise Indigenous land rights.

McKenzie’s spiritual connection to the land where he grew up harvesting fish and berries drove him to host rallies and candlelit vigils in Kamloops to oppose Trans Mountain. McKenzie’s elders taught him the Secwepemc law, X7ensqt, which translates to “the land (and sky) will turn on you” if you disrespect the land.

McKenzie’s breaking point came when his dad, a Skeetchestn councillor, came under pressure to sign agreements supporting Trans Mountain, which he declined. The pressure was more intense because his son, living right there in his house, was a leading face of pipeline opposition.

McKenzie left home to relieve the pressure on his parents. Although he can’t return home, he says he must keep fighting.

As McKenzie put it: “We have to protect the land and the water no matter what. Our survival depends on it."

Trudeau takes over

The ongoing battle against the Trans Mountain expansion and Coastal GasLink is part of a broader protest movement that blocked nearly every proposal to ramp up exports of coal, oil and natural gas from the West Coast for a decade.

Now British Columbia’s twin pipeline projects appear poised to punch two big holes in what activists called their Thin Green Line against fossil fuel exports from North America’s western coast.

Coastal GasLink is designed to feed natural gas from the province’s northeastern gas-fracking fields to an export terminal under construction near Kitimat, British Columbia, about 110 kilometers southeast of Prince Rupert. Coastal GasLink ignited a national uprising last year, when people across Canada orchestrated blockades and demonstrations to support hereditary chiefs from the Wet’suwet’en Nation who oppose the project — tensions that remain unresolved.

The fate of B.C.’s fossil fuel megaprojects — along with comparable developments worldwide — will help determine whether greenhouse gases can be slashed to contain the threat of catastrophic climate change. Climate scientists and, increasingly, even traditionally conservative energy planners such as the Paris-based International Energy Agency, say building new fossil fuel infrastructure undermines climate action.

Two pipelines would go across across a large swath of western Canada. (Mark Harrison)

Two pipelines would go across across a large swath of western Canada. (Mark Harrison)

Two pipelines would go across across a large swath of western Canada. (Mark Harrison)

British Columbia’s pipelines broke through with forceful government backing. Full-throated provincial endorsement launched Coastal GasLink, owned by Calgary-based TC Energy, in 2018. The same year, Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s C$4.5 billion acquisition of Trans Mountain secured its expansion project just after the Indigenous activists and their allies, against seemingly impossible odds, hounded the pipeline’s original developer, Texas-based Kinder Morgan, into essentially abandoning the project.

“This is a pipeline in the national interest and it will get built,” said Trudeau. The federal takeover changed the playbook for pipeline resistance.

“Our strategy was … making the projects such a headache [that] the companies were willing to abandon them. We got to that point with Trans Mountain. But we didn't prepare for a world in which the federal government bought the pipeline and assumed all the risk around it,” said Sven Biggs of Stand.earth, an activist group operating from offices in Vancouver, San Francisco and Bellingham.

The significance of Trudeau's move is hard to overstate. Trans Mountain’s expansion will triple its capacity to 800,000 from 300,000 barrels a day. The new line terminates at a shipping terminal in Burnaby, east of Vancouver, where the oil can be shipped for refining in Asia and where spur lines and barges link the pipeline to Washington state's refineries.

Mark Jaccard, a sustainable energy professor at Simon Fraser University, calculated that producing tar sands oil known as bitumen and pumping it to Burnaby would release the equivalent of 7.7 million metric tons of carbon dioxide a year in Alberta and British Columbia — as much as 2.2 million cars — while refining, distributing and burning the bitumen would release 71 million more metric tons overseas.

Farther north, the 670-kilometer-long Coastal GasLink pipeline is designed to initially carry 2.1 billion cubic feet of natural gas each day to Kitimat. There, the fracked gas is to be liquefied for export, emitting 4 million metric tons of carbon dioxide annually. The capacity of the pipeline and export facility could be expanded in future phases.

Trans Mountain and Coastal GasLink began building in 2019 and intend to begin pumping by the end of 2022 and in 2023, respectively. Each is roughly one-quarter built, but work has slowed recently amid environmental violations and safety incidents, including some connected to the coronavirus pandemic.

Anti-pipeline activists say the arrival of COVID-19 has cut both ways for their cause. On the one hand, it’s distracted people and made organizing harder.

On the other hand, in December the provincial health authority ordered British Columbia's pipeline projects to scale down the number of workers on site to reduce COVID-19 transmission. Safety regulators also ordered a two-month projectwide pause at Trans Mountain after a second serious worksite accident in recent months.

In January, the province ordered an audit of Coastal GasLink's erosion-control measures after officials discovered compliance violations and risks to watersheds along the pipeline route.

As of early last month, 76 kilometers of the Trans Mountain route — 8% of the total — remained to be finalized. A First Nation situated approximately 100 kilometers southwest of Kamloops is holding hearings on the risks Trans Mountain poses to its drinking water aquifer. The Coldwater band, a reserve in Nlaka’pamux Nation territory, is pushing Canada Energy Regulator to reject the proposed route.

Confrontation here, there, everywhere

Confrontation continues. On the coast and in interior British Columbia, people are regularly arrested for obstructing Trans Mountain work sites.

Frequent activity occurs in Burnaby, British Columbia, the terminus of Trans Mountain in the traditional territory of the Tsleil-Waututh Nation. Coast Salish community members occupy a watch house in Burnaby, where they keep vigil and host ceremonies to oppose the project. About five kilometers south of the watch house, activists inhabit a treehouse camp from which they work to delay Trans Mountain’s plan to clear roughly 1,300 trees adjacent to the salmon-bearing Brunette River.

Further resistance occurs along the pipeline route, such as in Secwepemc territory, where a group is fighting Trans Mountain from a camp of tiny homes near the Blue River community, 175 kilometers northeast of Kamloops.

Southwest of that camp, Romilly Cavanaugh was arrested in October with others after chaining herself to a worksite gate to delay construction. An environmental engineer who briefly worked for Trans Mountain in the 1990s, Cavanaugh said she got involved on the front lines because she had no other choice. “There is no way to take a dirty industry like that and make it clean,” she said.

Cavanaugh cites the carbon emissions the pipelines will spur and limited advancements in technology for cleaning up oil spills. Trans Mountain will increase tanker traffic by at least sevenfold in the Salish Sea waters shared by the U.S. and Canada.

Data from the International Tanker Owners Pollution Federation and Transport Canada lends credence to Cavanaugh’s concern. According to both the Canadian agency and the global tanker spill advisory organization, no more than 15% of oil is recovered in a typical spill. And spill recovery may be even lower for spills of the diluted bitumen carried by Trans Mountain, which is the heaviest form of crude. It tends to sink to the bottom.

“From my perspective, civil disobedience is the only option we have left,” said Cavanaugh.

Other activists continue hammering the financial front, with a little help from Trudeau. The prime minister unveiled a revamped climate plan in December, but heightened climate action by his government may not ease the pressure on British Columbia’s pipeline projects. In fact, in the hands of expert activism, it may do the opposite.

More than 100 Canadian economists and policy experts signed a letter to Trudeau questioning the viability of the Trans Mountain expansion in September 2020. The letter noted weakened oil demand amid the pandemic and doubts from oil giants such as Shell and BP about whether demand would “fully recover” after COVID-19. It also cited the International Energy Agency's conclusion that oil demand must decline by nearly a third over the next two decades to limit global warming.

Meanwhile, federal agencies and auditors have sharpened the experts’ attack on Trans Mountain’s viability. Just before Trudeau’s climate policy announcement, Canada Energy Regulator, the agency that oversees the Trans Mountain expansion, reported that tougher policies might cut oil use and thus eliminate the need for additional pipelines.

The parliamentary budget officer echoed that finding a few weeks after Trudeau’s announcement, writing that the federal government could lose money on Trans Mountain under strengthened climate policy.

Adding uncertainty to the financial stability of the project, at least three of the pipeline’s 11 big insurers recently walked away from Trans Mountain, under pressure from environmental campaigners.

Coastal communities convene

While most protests against the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion are happening on the land, the federal government has recognized that some of the project’s greatest risks concern potentially catastrophic spills on the water.

That’s because the expansion is expected to spur at least a sevenfold increase in the number of oil tankers plying the waters of the Salish Sea, the body of salt water shared by British Columbia and Washington state.

The Trans Mountain project includes three new tanker berths at its terminal in Burrard Inlet, on Burnaby’s northern shore. Charlene Aleck, a spokesperson for Tsleil-Waututh Nation’s Sacred Trust Initiative, which is fighting the Trans Mountain expansion, says the tanker traffic is essentially in her kitchen.

More than 90% of Tsleil-Waututh’s diet came from Burrard Inlet before settlers arrived, yet today community members, because of industrial pollution, consume very little from the inlet.

The Tsleil-Waututh Nation recently cleaned and restored a degraded clam garden in the inlet and has since hosted three successful clam harvests.

“We're able to maintain our Indigenous way of life, to be able to hand those skills down from grandmother to mother to daughter to granddaughter,” said Aleck.

The increased tanker traffic and elevated risk of an oil spill from the Trans Mountain expansion will “decimate” this project, she says. A recent Tsleil-Waututh report found that tugboats and tankers increase wave energy in Burrard Inlet, eroding nearshore ecosystems and “irreplaceable” archaeological sites.

Legal maneuvering over such marine impacts continues, in spite of a crushing defeat last year.

Tsleil-Waututh led a legal challenge that delivered a milestone victory for the anti-pipeline coalition in 2018, when a federal court overturned Trans Mountain’s federal approval. The decision cited the Canada Energy Regulator's disregard for marine impacts from increased tanker traffic, as well as insufficient consultation with Indigenous communities.

But in 2019, the regulator endorsed the project again, subject to more than 150 enhancements in safety, preparedness, environmental regulation and community engagement. And last year federal courts approved the package.

Still, pipeline opponents keep pushing. A recent gambit led by the Squamish Nation, northwest of Vancouver, seeks to exploit a 2019 British Columbia court order that requires Premier Horgan's NDP government to reevaluate environmental approvals awarded to Trans Mountain by the previous government.

Last month British Columbia’s environmental regulatory agency proposed two tweaks for public comment, and the province expects to complete its reconsideration of Trans Mountain’s approvals by early summer. Cities, environmental groups and First Nations are pushing for more.

One tweak would require Trans Mountain to issue reports every five years, detailing research that it is mandated to conduct on the behavior and recovery of spilled diluted bitumen. The second would require reporting on how marine spills could harm human health, including various pathways people could be exposed to spilled oil and solvents from Trans Mountain and ways to reduce those exposures.

“It doesn't go far enough. It doesn't go deep enough,” is how Andrew Radzik, energy campaigner with the Nanaimo, British Columbia, and Vancouver-based Georgia Strait Alliance, described the proposal. He said the province should specify objectives for the diluted bitumen spill studies, such as how seasonal conditions will impact what happens during spills, and require public consultation on those reports.

For the health report, he called for explicit inclusion of mental health impacts and for detailed reporting on how Trans Mountain will cover the cost of efforts to reduce identified health hazards to oil spill responders and coastal communities.

He also called for a shoreline response plan. It could clarify who will battle a spill at the shore and how they will be equipped and trained.

Radzik said that he feared the provincial government would shy away from such strengthened requirements, which could increase costs and add delays to the project. “They can't stop the project, but they can meaningfully impact it,” he said. “They seem to not want to.”

‘We will always be here’

In October, two days after Cavanaugh’s arrest, Miranda Dick laid down a blanket outside a Trans Mountain gate near Mission Flats, British Columbia, a community adjacent to the Thompson River, which Trans Mountain has drilled beneath repeatedly to install pipe. On the blanket, Dick’s sister cut her hair off. Moments later, she was arrested with others for breaching an injunction prohibiting unauthorized access to Trans Mountain work sites.

The 489-kilometer-long Thompson River is one of roughly 250 salmon-supporting streams and rivers in the Fraser River watershed transected by Trans Mountain. It hosts one of the largest Sockeye salmon runs in the world. The resulting threat to salmon populations is the project’s single greatest risk, says Dick, the daughter of hereditary Chief Sawses, who was also arrested two days before.

“I want to protect clean water for the salmon and our livelihoods, not to mention the other links in the chain. The bears, the eagles, everything that lives off of salmon,” said Dick.

Dick says her hair collected knowledge in the 2½ years she grew it out — knowledge she let go of that day. She said the ceremony symbolizes the grief and loss Trans Mountain brings her.

Secwepemc people have opposed Trans Mountain since 2013, asserting Secwepemc law on historically occupied lands that were never ceded to Canadian governments. They follow hereditary leadership, traditional governance systems that vary between nations. Title and authority pass down generationally through families but is also “granted on merit” after “many years of training in culture and tradition,” according to reporting this week by The Tyee. Hereditary leaders retain the authority to oversee their nations’ ancestral territories.

But some elected chiefs and band councils have chosen their own path on pipeline projects for their reserves — colonial land set-asides and Indigenous governments created, funded and overseen by the federal government under Canada’s Indian Act. As of February 2020, 58 First Nations had signed “mutual benefit" agreements with Trans Mountain.

The Whispering Pines Clinton Indian Band is one of four Secwepemc reserves with a signed agreement. Its elected chief, Mike LeBourdais, represents one of at least three First Nations groups seeking to purchase the project. His community will receive a share of operating revenue from the project, which he said would support education efforts, elders’ retirement programs and environmental oversight of the pipeline.

In an interview with InvestigateWest, LeBourdais said he signed the benefit agreement because he wants to have agency in the project. He said his lawyers assured him the project would be approved regardless of the circumstances.

“This is what I'm fighting for — to be in the conversation, in the economy of British Columbia and Canada,” he said.

Such divisions place the projects on unsteady ground, as the unresolved conflicts over the Coastal GasLink pipeline show. Central to the conflict is the Royal Canadian Mouted Police’s arrests of Wet’suwet’en land defenders in their territory, which galvanized a solidarity movement of blockades and rallies across the country.

The tension began to rise sharply in 2019, a year before the Canada-wide protests. On Jan. 8, 2019, RCMP officers breached a camp in Wet’suwet’en territory established in 2018 to oppose Coastal GasLink. The RCMP came armed with a court injunction and made 14 arrests.

Sleydo’ Molly Wickham, a member of the Wet’suwet’en Nation, was among those arrested that day. She recalls being “surprised and horrified” by the intensity of conflict.

Wickham’s clan, the Gidimt’en, is one of five clans within the Wet’suwet’en Nation. Hereditary chiefs representing all five clans are united in their opposition to Coastal GasLink. Since 2006, they have opposed all pipeline proposals in their territory, noting efforts to protect water, wildlife and their livelihoods.

And it is the centuries-old hereditary system that holds territorial power, as recognized even by Canadian law under a 1997 Supreme Court landmark decision stating that hereditary governance represents “all of the Wet’suwet’en people.”

Yet Coastal GasLink signed mutual benefit agreements with five out of the six chiefs elected by the federally created Wet’suwet’en bands. (The company also says it has awarded C$825 million in contracts to Indigenous and local businesses.)

Thus, the tensions were already high by February 2020 when the RCMP arrested about two dozen people in Wet'suwet'en territory to enforce a new project injunction. The conflict ignited national backlash. Mass demonstrations in solidarity with the Wet’suwet’en blocked highways, ports, rail lines and other infrastructure from coast to coast for as long as five weeks. Rallies disrupted traffic, universities and legislatures.

The conflict abated in March when the Canadian and British Columbian governments opened negotiations with the Wet'suwet'en over their land claims. But conflict could erupt again without warning.

The persistent threat of an uprising has even some ardent pipeline supporters seeing the opposition holding the upper hand. One Alberta columnist wrote last month that only Indigenous ownership can secure Trans Mountain's success, calling on Alberta’s premier to “convince the Trudeau Liberals to quickly strike a deal on Trans Mountain” with First Nations groups.

Wickham says it’s “inevitable” that conflict will flare up on Wet'suwet'en territory again since her community has not agreed to stand down. British Columbia Premier John Horgan has presented the liquefied natural gas sector as an economic growth engine, and currently four more proposed gas pipeline projects are pending.

Two of those projects would cross Wet’suwet’en territory. The Wet’suwet’en hereditary leaders, noted Wickham, oppose both.

“Wet’suwet'en will never ever go away. We will always be here,” said Wickham.

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher