- Details

- By Levi Rickert

Opinion. What a difference a week makes.

On Thursday, June 8, Indian Country loudly applauded the 7-2 U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling in the Brackeen v. Haaland that upheld the constitutionality of the Indian Child Welfare Act.

Then last Thursday happened. The Supreme Court — the same one that seemed to exhibit a basic understanding of tribal sovereignty in the Brackeen ruling — showed how little the high court justices know (or care) about our rights as sovereign nations in their ruling in Arizona, et al. v. Navajo Nation.

The 5-4 ruling against the Navajo Nation’s water rights felt all-too familiar. The high court rejected the tribe’s claims against the federal government in a long-running dispute over access to water from the Colorado River. The Navajo Nation spent decades trying to get the federal government to live up a treaty made a long time ago — nearly 50 years before the state of Arizona even existed.

We’ve seen this movie before and know how it ends: The federal government fails to honor a treaty with a tribal nation.

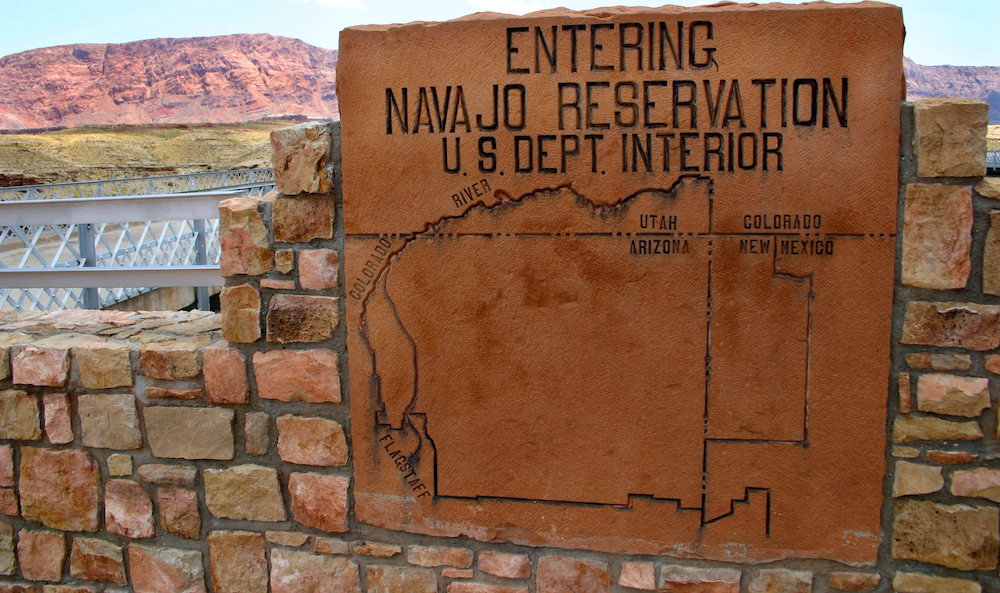

In this case, an 1868 peace treaty between the Navajo Tribe and the United States established the Navajo reservation, which spans 17 million acres and is about the size of the state of West Virginia. The reservation is located almost entirely in the Colorado River Basin.

In Arizona v. Navajo Nation, the present-day Navajo Nation contended that the treaty imposed a duty on the United States to take affirmative steps to secure water for the Navajo people.

It all makes sense to me. When signing a real estate sales contract, I have an expectation that water lines are connected to the house so that I will have access to the water.

Writing for the majority, Justice Brett Kavanaugh ruled that the federal government’s treaty promise to provide a permanent homeland to the Navajo Nation doesn’t require the government to take modest steps to secure the water needed to make it a viable homeland.

“It is not the Judiciary’s role to rewrite and update this 155-year-old treaty,” Kavanaugh wrote. His opinion essentially said the Navajo Nation should be dealing with Congress and the White House, instead of the Court to get water.

Associate Justice Neil Gorsuch, a conservative like Kavanaugh, disagreed. In a 27-page dissent, Gorsuch, wondered: “Where do the Navajo go from here? To date, their efforts to find out what water rights the United States holds for them have produced an experience familiar to any American who has spent time at the Department of Motor Vehicles. The Navajo have waited patiently for someone, anyone, to help them, only to be told (repeatedly) that they have been standing in the wrong line and must try another.”

Indian Country sees it as one more time the federal government disregarding their basic obligation to fulfill its trust responsibilities as given through treaties.

“The U.S. government excluded Navajo tribal citizens from receiving a share of water when the original apportioning occurred and today’s Supreme Court decision for Arizona v. Navajo Nation condoned this lack of accountability,” Native American Rights Fund (NARF) Executive Director John Echohawk said in a statement.

Rep. Raúl M. Grijalva (D-AZ), the ranking member of the House Natural Resources Committee, called the court’s decision dangerous.

“This is a dangerous decision that moves us backward to our shameful past in which treaties were promises not worth the paper they were written on,” Grijalva said. “Forcibly removing Indigenous Peoples from their full homelands is a violence we can never reverse. The Court’s majority states that when a treaty establishes a ‘permanent home’ for a tribal nation, the U.S. government doesn’t have to take the most basic steps to ensure the delivery of water needed for a livable home — let alone a permanent home.”

The sad reality is that about one-third of the 180,000 people on Navajo Nation don’t have access to clean, reliable water. That lack of water ripples across the Navajo Nation’s economy, affecting everything from health and infrastructure to food sovereignty and jobs.

After this week, the Supreme Court will head off on vacation until its next session in October. If there’s truth to recent reports about justices jet-setting around the world on billionaire-funded trips, I’m guessing the judges will be far too busy to think about the impact of their ruling on Navajo Nation.

Meanwhile, back on the reservation, Diné people will be getting in their cars and pickup trucks and traveling many miles to fill five-gallon containers with water, just so they can have one of the basic requirements of life.

The Supreme Court got it wrong with their decision last week. And once again, the federal government failed to fulfill its responsibilities. Given history, I should have seen it coming.

Thayék gde nwéndëmen - We are all related.

More Stories Like This

Jesse Jackson Changed Politics for the BetterNative News Online at 15: Humble Beginnings, Unwavering Mission

From the Grassroots Up, We Are Strengthening the Cherokee Nation

Friday the 13th: When Superstition Proves More Powerful Than Law

Congress Must Impose Guardrails on Out-of-Control ICE

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher