- Details

- By Levi Rickert

Opinion. Fourteen years ago this month, the South Dakota legislature passed an eleventh-hour proposal to change the state's statute of limitations on child sex offenses. The legislation made it impossible for any victim aged 40 or above to bring civil damages against people or institutions — including churches and schools — that should have known of the sexual abuse.

The 2010 measure was first brought to the legislature by Steven R. Smith, a South Dakota attorney for a Catholic entity that was being sued by dozens of Native Americans who claimed they had been sexually abused over decades at three Indian boarding schools run by the church.

Then-governor Mike Rounds, a Republican who now serves as South Dakota’s junior U.S. Senator, signed the bill into law in March 2010. With the swipe of his pen, Rounds undid scores of lawsuits for more than 100 Native American boarding school survivors against the Catholic Church and put South Dakota out of step with the rest of the country — so much so that another Republican lawmaker later said: “I'm told that what we did in 2010 made South Dakota a great place for pedophiles.”

South Dakota’s statute of limitations change stemmed from Native American adults who brought lawsuits against the Catholic Church. They wanted some level of justice for the sexual abuse they experienced at the hands of priests and nuns while attending Indian boarding schools.

Reading some of the cases from that time period revealed stories of Catholic priests molesting, raping and sexually abusing young Native American girls and Native American boys. If the priests’ sins were discovered, they were often given slaps on their hands and transferred to other institutions, where they had access to other Native American children they could victimize.

As I journeyed along the U.S. Department of the Interior’s “Road to Healing” tour last year, I heard of sexual abuse perpetrated in Indian boarding schools in every region of the country. The physical, emotional, and sexual abuse was not isolated to South Dakota – nor to the Indian boarding schools run by the Catholic Church.

Almost two years ago, our Senior Reporter Jenna Kunze brought to our attention the story of nine sisters from the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa who attended Indian boarding schools when they were little girls growing up in the 1950s and 60s. While there, they endured almost unspeakable sexual and emotional abuse at the hands of Catholic priests and nuns at the St. Paul’s Indian Mission boarding school in Marty, South Dakota.

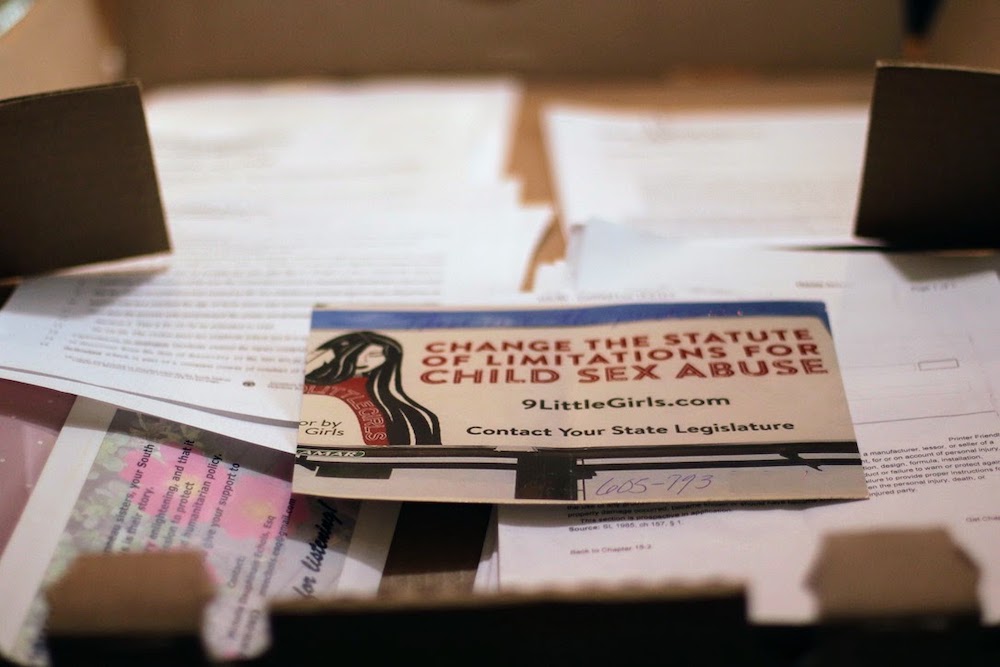

The sisters, as adults, have spent years attempting to seek justice, but were denied by the South Dakota legislature last-minute statute-of-limitations change in 2010. The law stripped them — and hundreds of other Native survivors of sexual abuses — the right to sue the Catholic Church. It deprived them of the opportunity to seek justice and find healing. For more than a decade, the sisters tried to overturn the law.

Last week, we published Nine Little Girls, a two-part series that tells the story of the nine Charbonneau sisters. Reported by Kunze, it was almost two years in the making. The story was slowed by the COVID-19 pandemic, which took the life of one sister. Another sister passed from cancer. And one other died of an aneurysm. So, Jenna waited with sensitivity so that she could properly capture the essence of the injustice experienced by the sisters and the family’s efforts to continue fighting for justice, despite the setbacks.

Other media outlets have reported on different aspects of this story over the years, so Native News Online is not the first publication to tell the Charbonneau sisters’ story. And I hope we’re not the last. This story needs to be told over and over again until the South Dakota legislature eliminates the statute of limitations on sexual abuses, especially those suffered by our elders during the assimilation era.

If our people are ever going to heal from the dark spot in American history called Indian boarding schools, we must allow justice to be part of the process. Truth must be sought, regardless of whether or not the criminal is dead or alive. It should not matter.

It is time for the remaining Charbonneau sisters and their families to be given justice. It is time for Native Americans to heal from the historical trauma brought by a dark era in American history. Justice brings healing.

Thayék gde nwéndëmen - We are all related.

Tell Us What You Think

More Stories Like This

Jesse Jackson Changed Politics for the BetterNative News Online at 15: Humble Beginnings, Unwavering Mission

From the Grassroots Up, We Are Strengthening the Cherokee Nation

Friday the 13th: When Superstition Proves More Powerful Than Law

Congress Must Impose Guardrails on Out-of-Control ICE

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher