- Details

- By Madonna Thunder Hawk

Guest Opinion. Today, I share with you the story of my experience on the ground during that monumental moment. I’ll talk about the way things unfolded and how those weeks under siege were the first domino in a series of events that catapulted our movement into the international spotlight — and also eventually led to the formation of the Lakota People’s Law Project.

By the time the standoff began that February, I was already a seasoned activist. I’d met with the local American Indian Movement (AIM) chapter in the Twin Cities in the 1960s, and I’d joined relatives in California to occupy Alcatraz. When the call went out from the people of Pine Ridge to help lead discussions to confront issues in their communities, I didn’t hesitate. Little did I know that a planned series of strategy meetings would turn into an epic, months-long siege that would threaten our lives and gain international media attention.

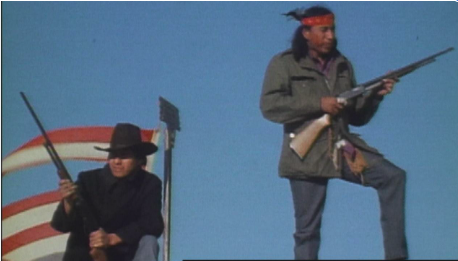

On the evening of February 27, 1973, after we finished talking with folks in a village called Calico, our caravan headed toward Porcupine. We were several miles north of Wounded Knee when the word went out that the feds were upon us. Armored personnel carriers had been spotted, and the Army, FBI, and other law enforcement agencies were converging on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation. We realized we had to get the caravan and our people to safety. And when we got to the village of Wounded Knee, the first firefight started.

Many people, including everyone in our car, got arrested that night, and for the first four or five nights of the occupation, I was in jail. Once released, I did what everyone else was doing: I loaded up on supplies and headed back to Wounded Knee. And there I remained until the siege ended more than two months later.

On the ground, it was minute to minute, day to day. It was a full military action, and we never knew what would happen. Firefights occurred almost every night, with flares and tracers raining down to light up the area. My job — I was one of four women doing this — was as a medic. We each had different bunkers to cover in case someone got shot. I was assigned four bunkers on the south side. Every night, it was nonstop activity. People would sneak in and out, hiding in the grass, bringing food and other supplies. Many were arrested. In that situation, you’re just trying to make sure everyone’s alive and healthy. If you couldn’t find someone, you wondered if they’d been killed or taken to jail.

During this time, I met Danny Sheehan, who would go on to lead several seminal legal justice fights and become our Lakota Law president and chief counsel. During the standoff, Danny was staying with my brother-in-law, Herman Thunder Hawk, in the house where we monitored government communications via CB radio. He was among many legal volunteers who showed up when it mattered most, and he stayed busy prepping criminal defenses for our people. It’s notable that no one was ever convicted after the standoff. All charges were eventually dismissed because of prosecutorial misconduct. The FBI had illegally wiretapped attorneys.

Those weeks under siege were hard, but they were worth it. We took a stand that mattered, and we held the world’s attention on nightly newscasts. We inspired later landback and occupy movements, and we formed connections that last until the present day. 32 years later, in 2005 — when South Dakota’s Department of Social Services wouldn’t stop taking our children — Russell Means urged me to talk with Danny again, leading to the founding of Lakota Law. We’ve been in this fight together, off and on, for half a century.

Madonna Thunder Hawk is the Cheyenne River organizer for The Lakota People’s Law Project.

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher