- Details

- By Professor Victoria Sutton

Guest Opinion. In the Presidential election of 2000 there was disbelief, and even outrage, that a popular vote would not determine the new president elect. But the U.S. Constitution, Art 2, Sec. 1 provides for electors to elect the President and Vice President:

Each State shall appoint, in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct, a Number of Electors, equal to the whole Number of Senators and Representatives to which the State may be entitled in the Congress. . .

The then, First Lady, Senator Elect Hillary Rodham Clinton included in her acceptance speech her promise to eliminate the Electoral College provision from the Constitution: "We are a very different country than we were 200 years ago, and I believe strongly that in a Democracy, we should respect the will of the people and to me, that means it's time to do away with the Electoral College."² Just this month, the Democrat candidate for Vice President , Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz, said, “I think all of us knows that the electoral college needs to go,” and stating that, "we need a national popular vote."³

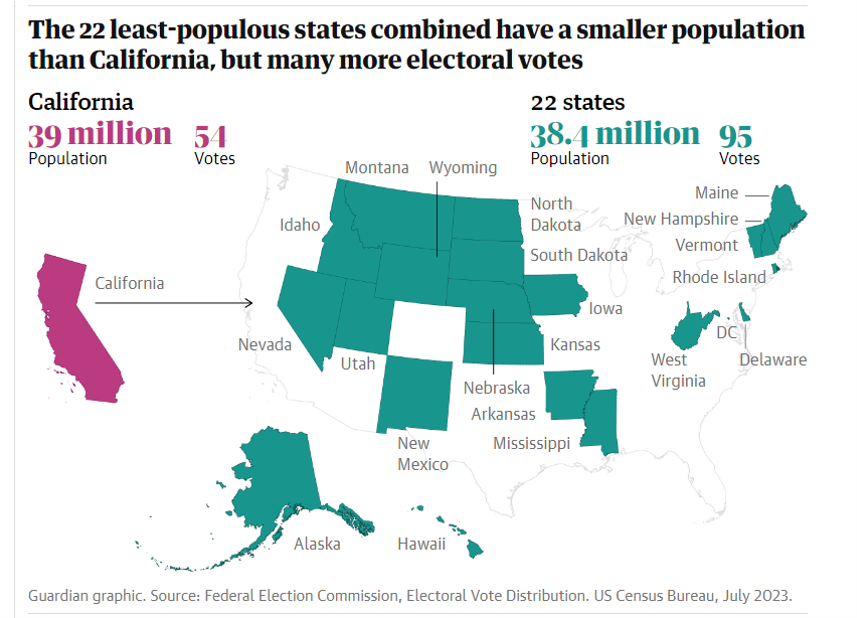

The Electoral College is intended to prevent power from centering in just the large states and to give more balanced power to smaller states. This graphic illustrates how this gives more voting power to smaller states:

Why is the Electoral College so controversial?

Electing a President that does not win the popular vote, is going to cause controversy. The U.S. Constitution’s Electoral College provision has caused controversy almost from the moment it was drafted.

This provision was utilized beginning with the first Presidential election of 1789. Interestingly, eight electors from New York failed to be appointed in time, and two from Virginia and two from Maryland did not vote. Rhode Island and North Carolina did not send any electors because they had not yet ratified the Constitution. This resulted in a total of twenty-four of the eighty-one electoral votes, not being cast.

The Electoral College has determined the outcome of only two presidential elections preceding elections of this millenia, where the popular vote gave a different result. Rutherford B. Hayes was elected in 1876 and Benjamin Harrison was elected in 1888, and neither won the popular vote. President John Quincy Adams did not win the popular vote against Andrew Jackson in 1824, but because neither received a majority of the Electoral College votes, the decision fell to the House of Representatives, which elected Adams.

The Electoral College provision was amended by the 12th Amendment to the Constitution in 1804.

The idea of the Electoral College has been challenged by the American Bar Association as "archaic" and "ambiguous."

Two constitutional amendments, proposed in 1997, included runoff provisions if a candidate did not receive 40-50% of the vote, requiring a runoff between the top 2 candidates. If these amendments had been in effect in 1992, when Bill Clinton received less than 50% of the vote, a runoff election would have been triggered between Bill Clinton and George Bush.

Madison’s Nightmare — Factionalism

Factionalism is "a number of citizens... united and actuated by some common impulse of passion... adverse to the rights of other citizens." Madison was concerned that these groups would expect their own interests satisfied at the expense of other interests; thereby posing a threat of overwhelming minority interests. In The Federalist No. 10, Madison proposed two different approaches to cure the problem of factionalism. First, remove its causes. But Madison explained that doing so would be "worse than the disease." That is, the very basis for our government would be threatened if groups were prohibited. Alternatively, Madison proposed to control the effects of factionalism through a republican form of government.

In The Federalist No. 10, James Madison advocated for the use of representatives in the election of the President to avoid factionalism:

[T]o refine and enlarge the public views, by passing them through the medium of a chosen body of citizens, whose wisdom may best discern the true interest of their country, and whose patriotism and love of justice will be least likely to sacrifice it to temporary or partial considerations. Under such a regulation, it may well happen that the public voice, pronounced by the representatives of the people, will be more consonant to the public good than if pronounced by the people themselves, convened for the purpose.

Madison believed that representatives were not deemed more competent, but rather the system of representation permits representatives with duties to represent the People to decide the synergies and coordination of governmental policies. Madison refers to the "public voice" through the representatives of the people to be "more consonant to the public good" than if individuals so convened.

Madison's confidence in the people is further supported by his trust in the republican system, not in the individual virtue of each representative, when he wrote, "It is in vain to say that enlightened statesmen will be able to adjust these clashing interests, and render them all subservient to the public good. Enlightened statesmen will not always be at the helm."

While James Madison and Thomas Jefferson held strong beliefs in federalism, they also supported the establishment of the Electoral College. Alexander Hamilton strongly believed that representatives possessed greater knowledge to select a President and Vice-President than the masses, writing: "A small number of persons, selected by their fellow-citizens from the general mass, will be most likely to possess the information and discernment requisite to so complicated an investigation."

Does the Electoral College stand the test of time?

Factionalism is controlled by a republic versus a pure democracy and the Electoral College supports a republican form of government. Claims that the system is “archaic” does not address the need to structure government to avoid factions that leave the smaller populations with no voice. Many believe the Electoral College is essential to give more voice to states with lower numbers of individual voters; and for the same reason, some believe this makes it unfair to the larger states.¹⁴ Some argue that the Electoral College was designed when only white, land-owning men were allowed to vote, thus it must be abolished. Yet, we are able to adapt this clause, as well as others as civil rights have expanded and changed.

It is predictable that efforts to abolish the Electoral College will continue, but so far, it has resisted change, and that may bring stability to the federal process.

To read more articles by Professor Sutton go to: https://profvictoria.substack.

Professor Victoria Sutton (Lumbee) is a law professor on the faculty of Texas Tech University. In 2005, Sutton became a founding member of the National Congress of American Indians, Policy Advisory Board to the NCAI Policy Center, positioning the Native American community to act and lead on policy issues affecting Indigenous communities in the United States.

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher