- Details

- By Levi Rickert

Opinion. Last Tuesday marked the 100th anniversary of women’s suffrage, when the 19th amendment guaranteed most American women the right to vote. The amendment was ratified on Aug. 18, 1920. Upon ratification, the amendment did not include American Indian women because American Indians were not yet citizens of the United States. It took almost four more years for America’s First Peoples to gain citizenship, on June 2, 1924.

Even after gaining citizenship, American Indians in some states were denied the right to vote because — similar to African Americans — they were subjected to poll taxes, literacy tests and sometimes intimidation. American Indians in New Mexico were denied the right to vote until 1962.

The 100th anniversary of women's suffrage allowed reflection on how far we have come in the United States and a look at the obstacles and challenges that confront us.

In 1968, a commercial promoting slim cigarettes used black and white suffrage photographs with the slogan, “You’ve come a long way, baby” at the cusp of the feminist movement.

In reality, for some Native women the “long way” actually was a move backwards because before European contact, several tribal nations maintained matriarchal governance, which was foreign to white settlers, who came from male-dominated cultures. Even while Native women had a voice within their tribal societies, such as the clan mothers within the Haudenosaunee Nations (Mohawk, Oneida, Cayuga, Seneca and Onondaga) in New York state, their voices were discounted for the most part by non-Natives.

Still, Native women held significant influence in many tribes across Indian Country. Through the years, Native women had led tribes with distinction, such as the late principal chief of the Cherokee Nation, Wilma Mankiller.

Separate from tribal leadership, two Native women were asked to run for vice president of the United States in recent decades. LaDonna Harris, a tribal citizen of the Comanche Nation and ex-wife of former U.S. Sen. Fred Harris (D-Okla.), was the Citizens Party vice presidential nominee in 1980. She was the first American Indian woman to run for vice president. Winona LaDuke, a tribal citizen of White Earth Ojibwe Nation, ran for vice president with Ralph Nader in 1996 and 2000 on the Green Party ticket.

During the fall of 2018, I watched the polls closely in two particular congressional races: the New Mexico’s 1st Congressional District and Kansas’s 3rd Congressional District, because two American Indian women were running to become the first American Indian women in Congress.

In April 2018, I interviewed Sharice Davids (Ho-Chunk) in a Las Vegas hotel coffee shop while covering the National Indian Gaming Association’s annual conference. There she sat, a Cornell Law School graduate and former Obama administration staffer seeking the Democratic Party’s nomination for Congress for the Kansas seat in a field of six contenders, confident as she explained to me why she thought she could win the nomination and go on to defeat the incumbent, Rep. Kevin Yoder. I smiled to myself.

I saw fire in her eyes that day — a true Native warrior.

During her race to win the nomination, Sen. Bernie Sanders flew into the district to hold a rally for one of her Democratic opponents. On the Republican side, Vice President Mike Pence visited the district to assist Yoder in a fundraiser. The odds did not look good, but Davids won the primary.

A week before the November election, I traveled to Olathe, Kan. to cover history being made. It was a big deal for an American Indian woman to become a member of Congress and the polls looked favorable. Shortly after the polls closed, the national television networks announced Davids’s victory. Walking into the ballroom where her victory celebration was underway, I saw other American Indians with smiles on their faces and tears in their eyes. They all knew, like I did, that one more glass ceiling had just been shattered.

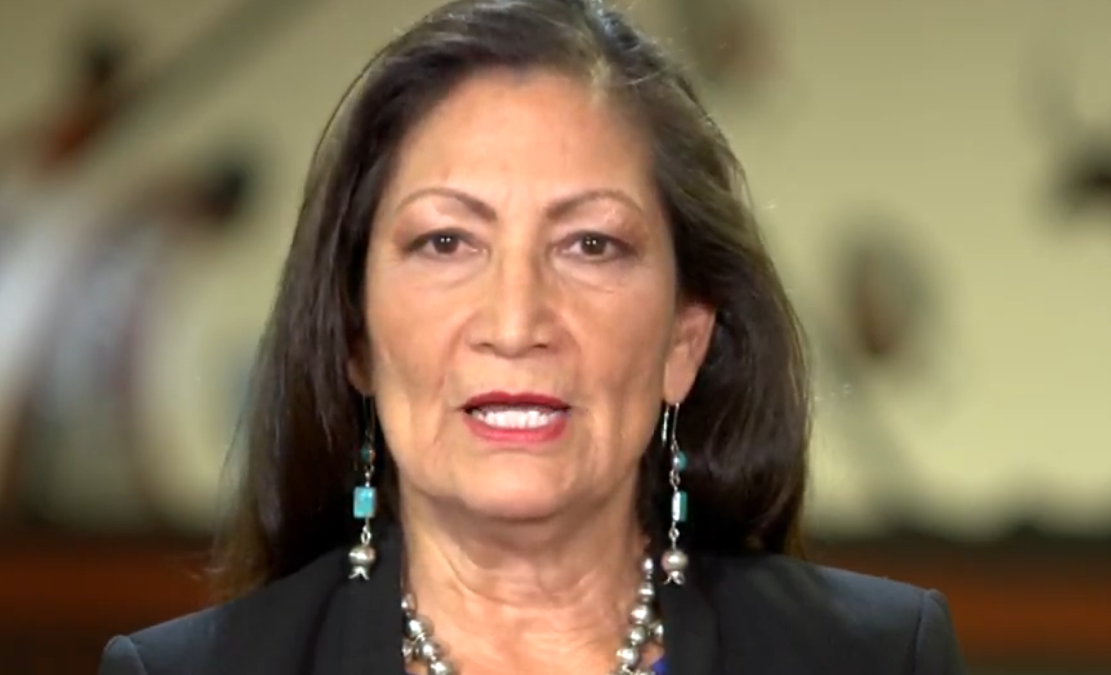

A little more than 500 miles away, Deb Haaland (Laguna Pueblo) celebrated victory in New Mexico’s 1st Congressional District in Albuquerque.

It took until the 116th Congress for two American Indian women to gain entry.

That same election night in 2018, Peggy Flanagan (White Earth Ojibwe) became the highest-ranking elected official in the nation at state level, when she was elected to be Minnesota’s Lieutenant Governor.

During the 2008 presidential campaign, then-candidate Barack Obama made a speech on race relations that became known as his “A more perfect union” speech. Taken directly from the preamble of the U.S. Constitution, the premise of the speech was that this country has had its imperfections since its birth and that the movement towards perfection is a continuum.

Last month, as Obama eulogized iconic civil rights leader and Congressman John Lewis, the former president reminded the nation of this theme.

With the election victories of these three Native women, the nation got closer to perfect. The nation made progress.

This November, Indian Country has the opportunity to take another step closer to perfection by going to the polls and electing more Native women to office.

This election season, remember the words of Rep. Deb Haaland to millions of viewers during the final night of the Democratic National Convention: “Voting is sacred.”

It’s been 100 years since the women's suffrage movement. But there’s still a lot of work to do.

More Stories Like This

Native News Online at 15: Humble Beginnings, Unwavering MissionFrom the Grassroots Up, We Are Strengthening the Cherokee Nation

Friday the 13th: When Superstition Proves More Powerful Than Law

Congress Must Impose Guardrails on Out-of-Control ICE

Housing and Support Services: The Key to Restoring Justice

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher