- Details

- By Dr. Aaron A. Payment

When asked by an anthropologist what the Indians called America before the white man came, an Indian said simply, 'Ours.'

- Dr. Vine Deloria, Jr.

OPINION. In advocating advanced appropriations, and full and mandatory funding, we must realize that Indian Country funding is not welfare; not reparations, and not even a social justice concept for bringing American Indians to near extinction or the worst of federal Indian policy like “Termination.” The obligation is borne out of the over 500 million acres of land tribes ceded in exchange for “health, education and social welfare” for tribes. Think of the treaty and trust obligation as a mortgage for which the tribes “paid in full” with our land and for which the federal government is forever obligated. When some ask why honor such antiquated documents as Indian treaties, I remind them that treaties are pursuant to the U.S. Constitution which is older and a government is only as good as its word.

Federal Indian Policy: U.S. Constitutional Origins

As we enter what may be a new era of federal Indian policy with the Biden administration, it is important to recognize the origin of the treaty and trust responsibility. My first graduate thesis in the 1990s was Federal Indian Policy and the ebbs and flows depending on who is President, who make up the Legislature, and who preside as the U.S. Supreme Court. Suffice it to say, the government to government relationship is predicated in the Northwest Ordinance, memorialized in Article I, Section 8, Clause 3 of the U.S. Constitution, and over a century of judicial precedence, administrative recognition through Executive Order and Presidential Memorandum, and Legislative appropriations that recognize the treaty and trust obligation.

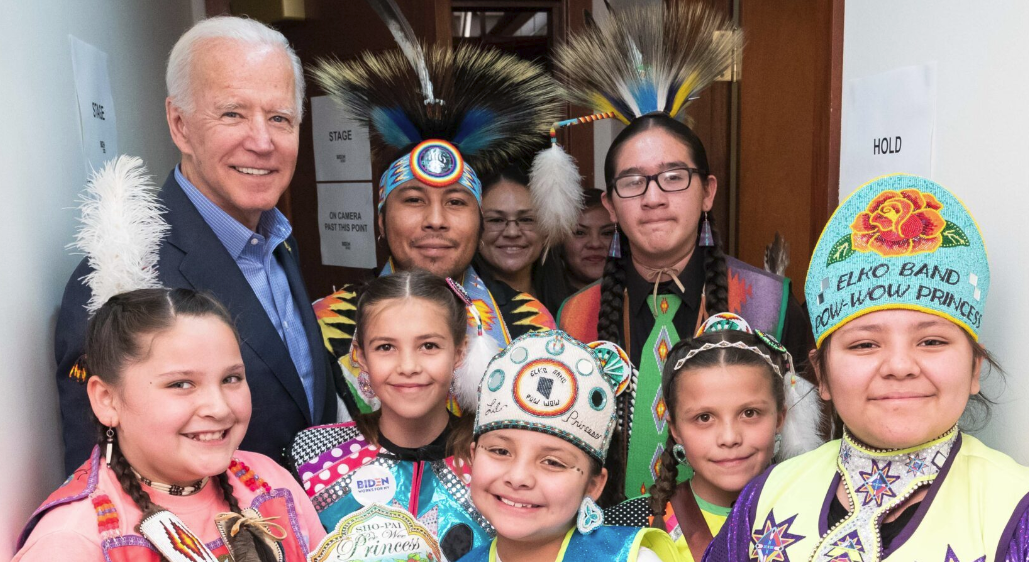

With a new President following a solid campaign policy platform for Indian Country, expectations are high for substantive results which have already included the historic nomination of an American Indian, Debra Haaland (Laguna Pueblo) for a presidential cabinet position as Secretary of the Interior.

Transition Recommendation Primer

What follows are a list of recommendations I have advocated during countless sessions with the Biden Transition Team in preparation with what I anticipate will be a more comprehensive Consultation Policy issued through a new Executive Order. While Presidents Clinton and Obama set the expectation for tribal consultation, it remains fact that the 2019 GAO report identifies which agencies and subdivisions have just not complied. Of pre-eminent importance is the articulation of a new Executive Order for a new era which recognizes the treaty and trust obligation including full funding for the IHS, BIA, BIE and all federal funding to tribes. Tribes have long advocated that these funds should move from competitive to formula and self-governance type funding to allow for maximum tribal flexibility to meet our needs as we see fit. The trickle-down methodology from states to tribes like the Affordable Care Act (ACA) Medicaid Expansion, SAMSHA, Head Start, LIHEAP for example, subordinates tribes to states which is inconsistent with the Commerce Clause that recognizes tribes as sovereigns at par with foreign nations and states.

FUBI – For Us By Indians

Next, modifying the FUBU motto to “For Us By Indians” (FUBI) means a more clear demonstration of our role in history and in the incoming Administration. The nomination of an American Indian to a cabinet level position is a commitment whose time is long overdue. As a member in good standing at the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI) and 1st Vice President, I sponsored the approved resolution to call for a cabinet position and specifically for the Department of the Interior secretary. Diversity in the new administration, however, should not begin and end with the secretary of the Interior. Beyond Presidential appointments, the real work begins after January 20th where we will see how substantive this commitment turns out to be. Under the Obama-Biden Administration, the White House Council on Indian Affairs compelled the collaboration of all Cabinet positions to substantively and collaboratively address Indian Policy and the manifestation of the treaty and trust obligation. This function was led by then Secretary of Interior Sally Jewell. Knowing that this project management function will be performed by an American Indian as Secretary of the Interior is very satisfying.

The resumption of the White House Council and the return of the White House Tribal Leadership Conference (please change the name to Summit) is another step to recommit to Indian Country. Funneling all tribal advisories (statutorily or administratively created) with the chairs of each to make up a new White House Council Tribal Advisory will ensure alignment of Indian voices with Federal Administrative voices. To ensure transparency and accountability, a running score sheet of “successes” and “work in progress” should be reported out in an annual report to Indian Country and play a key role in budget formulation as a predicate and justification for the President’s budget proposals.

Equity for Real

In the midst of two national crises, both the pandemic and the economic threat of recession, issues of equity should be assured during federal relief proposals. When the 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act was enacted, it provided for less than ½ of one percent relief to tribes. More recently, when the 2020 CARES Act was approved, it provided $8 billion (Congresswoman Haaland proposed $20 billion) or about 1 percent relief to tribes. The current percentage of the $900 Billion approved by Congress provides 1 percent to tribes. While tribes are obviously grateful, ensuring equity and honoring the treaty and trust obligation suggests the percentage relief should approximate the percentage of the U.S. population American Indians represent. Going forward, to achieve equity, any relief bills—economic or pandemic—should include a tribal set aside of no less than 2.5 percent.

Health

Full realization of the treaty and trust obligation with respect to the “health” in “health, education and social welfare” should include equitable distribution of Covid19 Vaccines, funding for IHS at not less than $20 billion and potentially up to $48 billion, treating tribes as a 51st State for ACA Medicaid Expansion and creating a new Indian Health portability card like veteran health. Further, moving key Indian funding from discretionary to mandatory is a must. Treaties are not discretionary so our funding should be mandatory - as I often say, “It’s a Trust Thing.” American Indian contraction of the Covid-19 virus and death as a result has shown that as the highest risk population, we have also experienced death as an outcome at multiples of the general population. This should not surprise us as the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights Broken Promises report shows we are the most vulnerable population. Another outcome of the pandemic is to expose the practice of relegating American Indians as “Other” or “Something Else” rather than through accurate data collection. This must change if we are to fully understand how well the federal government is fulfilling the treaty and trust obligation. In any analysis, before you can project milestones, you must start with accurate baseline data.

During the Trump Administration, the U.S. Office of Minority Health (under Health and Human Services) the Tribal Health Research Advisory Council was abolished without Consultation with tribes. This advisory focused on tribal health disparities and included tribal voices. This function needs to be returned. Next, the NIH Tribal Consultation Advisory needs to be empowered to ensure a tribal voice along with Consultation to increase participation in the All of U.S. cancer moonshot initiative. Nonetheless, make no mistake, the federal commitment to American Indian health care is not because of the worst of the worst health outcomes, but is due to the “health” provision in treaties as tangible remuneration.

Education

An often-ignored secondary provision of these same treaties is “education” which unfortunately has been relegated to the beneficence of the 7 percent of tribal children who attend Bureau of Indian Education (BIE) funded schools. While it is argued that the remaining 93 percent of tribal children who attend public schools benefit from Title VI Indian Education and other civil rights title equity funding, this treaty obligation has been largely allowed to follow. Alaska Natives are left entirely out of BIE or tribal school funding. As an American Indian high school dropout who went on to earn three graduate degrees and a doctorate, I believe in educational opportunity and fulfilling the treaty obligation for education. I am excited to see what new opportunities a Biden-Harris Administration and a New Era in Federal Indian Policy may usher in. Lifting the moratorium of new BIE schools including Alaska Native Villages and expediting tribal school construction is a must.

As the Broken Promises Report demonstrates the dropout rate for Native students is highest of any racial or ethnic group: 13.1 percent of male students (ages 16–24) and 9.9 percent of female students (ages 16–24) have dropped out, as compared with 7.2 percent of male students (ages 16–24) and 5.2 percent of female students (ages 16–24) of all races. Only 17 percent of Native students begin college, as compared to 62 percent of all students nationwide. While I strongly support, “mending not ending” public instruction, the understanding of a pre-eminent right to and education enshrined in treaties means American Indians are the only population of Americans with a U.S. Constitutional Right to an education.

While all other Americans have a right to education pursuant to the Equal Protections Clause of the 14th Amendment, American Indians “Pre-Paid” for our education, this suggests not just an equal protection right for American Indians but something more. Thus, to fulfill the “Education” obligation in treaties, a new opportunity for self-governance type funding for American Indian Education is sought.

I envision this commitment realized as supplemental rather than supplanting funding to ameliorate the worst disparity in education experienced by any racial ethic group4 in order to fulfill the treaty obligation. Title VI and Johnson – O’Malley funding is necessary but hardly sufficient as it doesn’t come close to meeting our needs. Of course, any new commitment for public community college funding, should also include fully funding tribal colleges as a fulfillment of the treaty obligation for education. As a former University Instructor, BIE Tribal School Board President, Vice President of a Tribal College, Member of the National Advisory Council on Indian Education and Title VI Parent Committee Member, I have some ideas for Indian Education Reform.

Social Welfare

There are numerous additional policy and funding commitments a New Federal Policy Era could usher in like reauthorization of VAWA with key tribal provisions, greater capacity building for tribal governments and strengthening tribal jurisdiction, greater data collection and collaboration with local law enforcement for Murdered and Missing Indigenous People, greater data collection and state conformity with the Indian Child Welfare Act, a Clean Carcieri Fix, expediting tribal land into trust requests; and ensuring UNDRIP precepts of pre-and prior informed consent which priorities treaty rights, sacred sites, and environment protections of our Mother Earth and waters.

The recently approved $900 Billion relief package with the extension tribal expenditure deadline of the 2020 Cares Act is a start. Unlike state funds, tribal funds in the Cares Act, while well intended, carried with it a level of paternalism for which the U.S. Federal Indian Policy has long been characteristic. With a new President, a female Vice President, and a Native Woman reaching a Cabinet post, it is my hope the era of paternalism is over. While I am optimistic, the proof will rest with substantive policy change. This editorial is just one humble American Indian’s opinion. Tribes are not monolithic which underscores the need to reach out and “Consult” with tribes beginning on day one of the new administration. Tribal leaders are encouraged to sharpen your pencils and ready your policy proposals. Self-determination necessitates we listen carefully to our ancestors and fulfill their expectations and walk the path they cleared for us. This means advocating in their memory, for the beneficence of our people today and for countless generations to come.

Dr. Payment is the chairperson of the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians, 1st Vice President for the National Congress of American Indians, and holds a Master’s in Public Administration, Master’s in Education Administration, Master’s in Education Specialist, and a doctorate in Educational Leadership.

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher