- Details

- By Catherine Buchaniec and Julia Shapero

Laz Carreon was on parental leave helping care for his newborn daughter when a mysterious respiratory illness first appeared in Wuhan, China.

As the illness spread through China, it caught his attention. An experienced registered nurse and former National Guard member, Carreon started monitoring the news, looking for any updates on the situation. The more case numbers rose, the more he got hooked, he said.

Carreon returned to his job at the Indian Health Board (IHB) in Minneapolis — a health-care clinic serving the area’s Native American population among other residents — in January 2020. By then, he said, he knew that the virus, which had begun to creep into Europe, was going to be a vast problem for both the clinic and the country.

“It kind of became an obsession in a way where I was monitoring this daily,” Carreon said. “You're seeing these hospitals that are just completely overrun.”

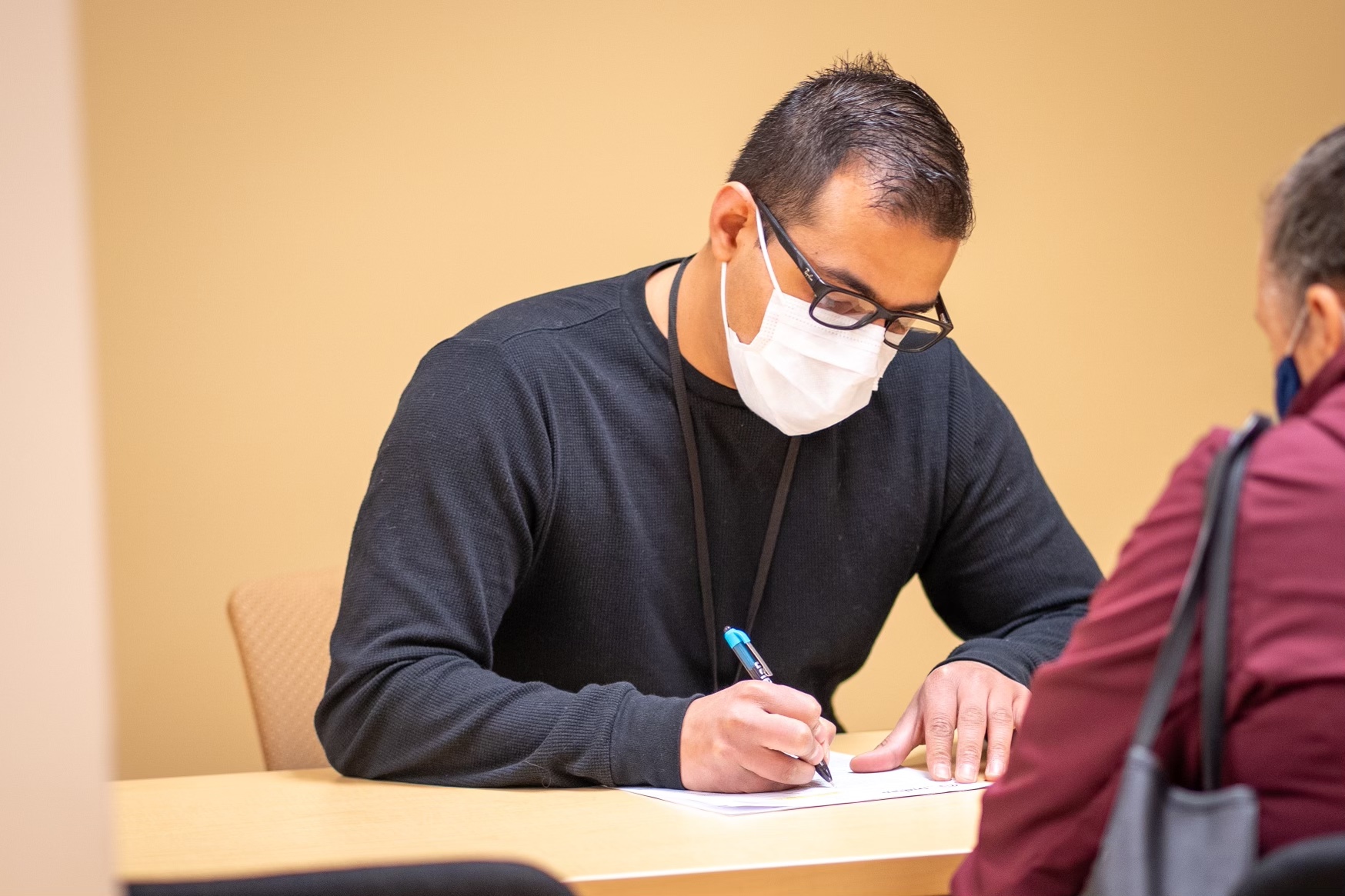

Over the next two years, he served as IHB’s COVID-19 manager, leading the small clinic through the ups and downs of the different virus waves.

During the pandemic, the country’s Native population suffered disproportionately from COVID-19, with higher rates of infection, hospitalization and death. But throughout the chaos, Carreon was able to maintain high levels of personal protective equipment (PPE), tests, and vaccines at the clinic, despite nationwide shortages and changing health guidelines.

After returning from parental leave, he said, he kicked into gear. He started wearing a mask at IHB meetings despite getting some strange looks. Mass orders of PPE were quickly signed off on. The clinic had a closet full of PPE taking shape even before the first cases were reported in the United States.

For the next two years, Carreon would attend meetings with the Minnesota Department of Health, the Indian Health Service, various tribal organizations, and even the White House to try to stay ahead of the next wave.

IHB started testing patients for COVID-19 in mid-March of 2020 and saw its first case in April. As of February 2022, the clinic had administered 4,949 tests, with 9% coming back positive.

Patrick Rock, the clinic’s chief executive officer and medical director, said it was prepared at nearly every stage of the pandemic. While other clinics in the area struggled to gain access to PPE and later, vaccines and antiviral treatments, IHB gained first access, he explained. The reason? Carreon’s initiative.

Although Carreon’s pre-emptive actions would eventually pay off, he said his worry might have appeared a bit odd to onlookers. But IHB, he explained, was always supportive, with Rock and other members of IHB leadership approving his requests.

Rock explained that IHB didn’t have the option of skepticism. If Carreon’s worst fears were confirmed, COVID-19 would soon be a concern in the U.S. as well, especially for the Native population.

“Pandemics have not been kind to Native Americans,” Rock said. “The historical trauma that people have brought into this context [means] that this is not a new concept for us.”

Smallpox, viral influenza, measles, and other infectious diseases brought by Europeans devastated the Native community, killing an estimated 90% of the Indigenous population in the Americas.

“Thinking about prevention and protection are not concepts that are, ‘Oh, this is crazy – why do you want to do this?’” Rock said.

Carreon said his early attention to COVID-19 in other countries traces back to his time in the military, which expanded his worldview.

“I just feel that we're in a very interconnected world, and small actions across any place can have an effect,” he said.

Born in Texas in 1987 and raised in southern Minnesota, Carreon came from a military family. In 2006, he joined the National Guard. After six years in the National Guard, he decided to enter the health-care profession, inspired by his sister-in-law, who worked as a nurse.

Carreon attended Rasmussen University, graduating with a degree in nursing. While there, Carreon learned of a medication-assisted treatment program for drug-use disorders in Woodbury, Minnesota called Valhalla Place. Medication-assisted treatment utilizes medications like methadone and suboxone to prevent relapse.

Carreon took a particular interest in treating drug-use disorders and stayed at Valhalla Place for almost six years, eventually becoming director of nursing and helping the program build three clinics.

After leaving Valhalla, he worked as the nursing supervisor for a clinic of the White Earth Nation, which was developing a medication-assisted treatment program. Although it began as a partnership between Valhalla and White Earth, Carreon said he helped White Earth build out its own program.

He moved to IHB in November 2019 as its nursing supervisor. Building off his earlier work on the virus, Carreon became interim COVID-19 manager in July 2020. A year later, his position became permanent, after the clinic realized that the pandemic would last longer than initially expected.

Carreon focuses solely on IHB’s pandemic response, supervising a team of nurses and other health-care professionals, including Katherine Medina, the clinic’s COVID-19 coordinator. Joining the team last year, Medina reaches out to different communities to connect them with COVID-19 resources.

“Even just the few months that I've been here, it really seems like IHB is on top of things,” Medina said. “Just comparing it with some of our neighbor clinics, we've always been right ahead of the curve, always.”

Medina explained that Carreon has a knack for finding resources during times of scarcity, either tracking them down through the federal and state governments or from other community contacts.

It all goes back to being in the decision-making room, Carreon said.

“We just try and get involved in anything that's possible and get the resources for patients,” Carreon said. “By being involved in this, we're able to provide services and continue to stay safe.”

IHB was one of the first clinics in the area to have access to vaccines and, later, antiviral treatments because of Laz’s foresight, Medina said. The clinic was able to start administering vaccines on Dec. 23, 2020, and received and was able to begin treating patients with the new antiviral drugs paxlovid and molnupiravir in December 2021.

While other health-care providers tried to return to normal operations throughout the past two years, Carreon consistently had his eyes on the next wave, Medina said.

Although U.S. cases dipped last summer, Carreon said his eyes were on the delta variant in India, monitoring case numbers and the path of the virus. When the strain hit the U.S., IHB was ready.

Now, his attention is glued to the United Kingdom and Europe. In a few days in late March, both areas saw a dramatic jump in new cases of the BA.2 subvariant of the virus, the sister strain of the omicron BA.1 variant that has become the predominant strain.

“Everything that happens overseas, it's just a matter of time before it comes here,” Carreon said.

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher