- Details

- By Monica Whitepigeon

DETROIT — For 27 years, Fay Givens (Choctaw/Cherokee) has walked the hallways of American Indian Services, Inc. (AIS), which provides health and wellness services, youth programs and other resources for the Urban Native population in metro Detroit.

As one of only two executive directors in the organization’s 49-year history, Givens maintained a positive and supportive workplace with little employee turnover. Families utilized the organization’s services and participated in cultural events there for decades.

Now, Givens must say goodbye to coworkers she’s known for over 20 years.

The Lincoln Park, Mich.-based nonprofit was already vulnerable from funding shortfalls before additional budget cuts and dwindling Medicaid funding appeared on the immediate horizon. Despite the CARES Act and grassroots fundraising, the economic constraints of COVID-19 have taken its toll on AIS.

After much discussion and assessment, Givens and the AIS board thought it best to suspend operations as of July 10, 2020.

“I’ve been blessed to do this every day for our people,” says Givens.

Amidst the need to its furlough employees, all ten AIS staff continue to come into the office to tie up loose ends. Since the start of the pandemic, every Wednesday the team would deliver medication, pickup supplies and make food deliveries to their more vulnerable clients.

“Our [Native] values are so good,” claims Givens. “What we value, we protect.”

Detroit’s Urban Native population equates to 30,000 people who identify as full or partial American Indian. AIS provides support to all 12 tribes in Michigan, especially the Sault St. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians.

According to Givens, 75% of Native people live in Detroit city limits and will be deeply affected by the closure.

While American Indian Health and Family Services will remain open in the city, AIS went beyond healthcare and acted more as a home away from home for many Natives in the area.

AIS programs and resources include trauma-based therapy, after-school youth programs that focus on bi-cultural issues, food distribution to approximately 6,000 people, case management, a myriad of referral options, weekly fitness groups, and cultural activities.

Givens reminisces about past powwows and art shows, where AIS partnered with Wayne County to bring different communities together, including a mini-powwow at a local prison.

“[It] gave me inspiration,” says Givens. “It’s important to have avenues for [Native] art to be pursued and seen.”

Recognizing the need for Native voices to be heard, especially in urban populations, Givens and her team would regularly advocate for Native rights by speaking annually with the United Nations, enforcing ICWA regulations and collaborating with other local organizations.

Detroit priorities do not seem to align with Native concerns, and Native people are frequently excluded from diversity and inclusion conversations. Like many marginalized communities, Native people have to fight relentlessly to explain their perspective and history to seemingly deafen city officials and other authority figures.

“For 27 years, I’ve given Indian lessons,” says Givens about the adversarial relationship with the Detroit government. “They don’t care at all about us. They’ve done nothing. Red lives don’t matter a whole lot.”

According to Model D’s Metro Detroit’s cultural history, “the underrepresentation of Indigenous peoples in Detroit, especially contemporary inhabitants as opposed to historical groups, has allowed the narrative of Detroit's Native Americans to focus far too much on the past, rather than current issues facing families in Detroit.”

Michigan has its own history of racial segregation, especially in Detroit. For the past 60 years, the city’s population has declined as more youth move away as the city combats urban decay, auto industry collapse, segregation and politics.

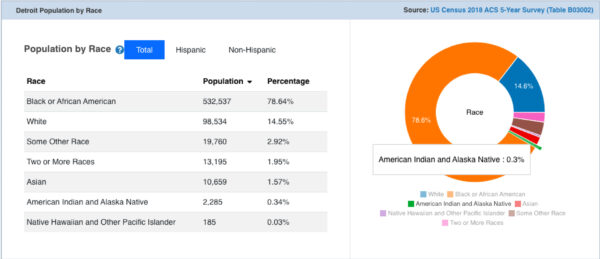

In a 2018 US Census ACS Survey, Detroit’s population breakdown showed only the Native population at 0.34% or 2,285. Meanwhile, many Natives could also fall into categories like “Some Other Race” or “Two or More Races,” which only further obscure results and do not accurately represent numbers that affect city budgets.

Demographic breakdown image from Detroit, Michigan Population 2020

Demographic breakdown image from Detroit, Michigan Population 2020

Givens hasn’t lost faith and will continue to support the Native community to the best of her ability. She plans on remaining in Michigan with her three children and 12 grandchildren. Her love of art and culture may one day provide safe spaces for Native artists to develop and showcase their work.

“There is a lesson to be learned from all of this and the world needs to go in a different direction,” claims Givens.

More Stories Like This

End of Enhanced Obamacare Subsidies Puts Tribal Health Lifeline at RiskSanta Ynez Tribal Health Clinic to Host Free Pediatric Dental Clinic

Rez Vet Earns Global Recognition for Serving Navajo Nation's Animals

Chickasaw Nation Governor Bill Anoatubby leads groundbreaking for pediatric clinic

Cherokee Nation Eyes $4 Million Transitional Housing Program