- Details

- By Levi Rickert

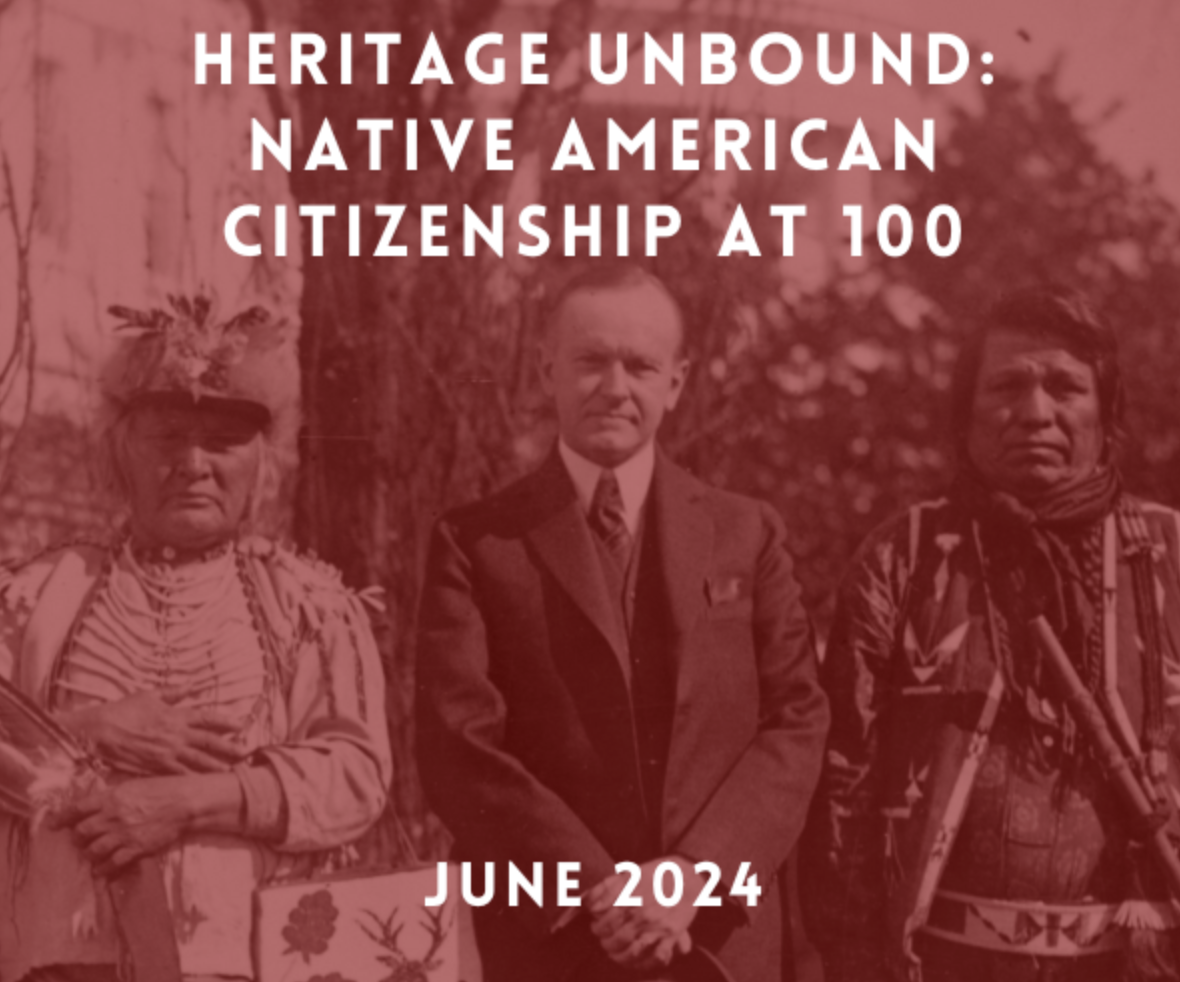

Opinion. Today is the 100th anniversary of the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924. Also known as the Snyder Act, the law granted dual citizenship to tribal citizens of federally recognized tribal nations.

The Snyder Act was named for Rep. Homer Snyder, a New York congressman, and signed by President Calvin Coolidge on June 2, 1924.

With a stroke of the pen, some 125,000 of the 300,000 Native Americans alive in 1924 became U.S. citizens. The other Native Americans were already U.S. citizens because of land ownership, intermarriage, treaties, or court decisions.

The 300,000 Native people alive in the early 1920s was a far cry from the tens of millions who lived here in North America before European contact in the 15th century. Over the course of several centuries, millions of Native Americans died from the spread of disease, war and genocidal practices by non-Natives.

In 1906, some 18 years before the Snyder Act became law, President Theordore Roosevelt wrote the foreword for a book by Edward S. Curtis, the photographer who took over 40,000 photographs of Native Americans at various tribes in the West. In the foreword, Roosevelt praised Curtis for his work because the common thought then was that American Indians were a “vanishing” people and it was important for historical records to be kept.

“The Indian as he has hitherto been is on the point of passing away. His life has been lived under conditions thru [sic] which our own race passed so many ages ago that not a vestige of their memory remains. It would be a veritable calamity if a vivid and truthful record of these conditions were not kept,” Roosevelt wrote.

Throughout history, the federal government maintained various policies to eliminate Native Americans. When it became apparent they could not kill all the Native Americans, the policy switched to assimilation of Native Americans into the general population. One policy that emerged to accomplish the assimilation process was the Indian boarding school era. The mantra was to “kill the Indian, save the man.”

By the time Coolidge, who had become president when President Warren Harding died in office, signed the Indian Citizenship Act, the practice of assimilation was in full motion. Throughout his presidency, Coolidge showed an affinity to Native Americans. Maybe it was his belief that he had some Indian blood in his veins. In his published autobiography, Coolidge claimed that his father had a “marked trace of Indian blood.” In 1927, he became the first U.S. president to visit an Indian reservation when he visited the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota.

..

What makes his June 2, 1924 signature on the Snyder Act remarkable to me is that just one week earlier he had signed the Immigration Act of 1924, which almost entirely forbade “aliens ineligible for citizenship” from Asia and the Middle East. During the early part of his presidency, Coolidge often said that “America should remain Americans.”

The signing of the Snyder Act came with complexities. Several tribes, including the Onondaga Nation resisted the concept of becoming U.S. citizens because they thought it treasonous. In 2017, Joseph Heath, general counsel of the Onondaga Nation, wrote: the Onondaga and the Haudenosaunee “have never accepted the authority of the United States to make Six Nations citizens become citizens of the United States, as claimed in the Citizenship Act of 1924.” He continued that accepting citizenship would be “treason to their own Nations, a violation of the treaties and a violation of international law, as recognized in the 2007 United Nation Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.”

As I reflect on the Indian Citizenship Act, I believe the signing of the Act was a firm affirmation that the federal government’s genocide of Native Americans was officially over. While the signing of the Act did not solve many problems for Native Americans, it safeguarded from being killed by our government.

In his new novel “Wandering Stars,” award-winning author Tommy Orange writes about the Indian Citizenship Act:

“And in 1924, Indian citizenship will have been granted, even though they will mean to dissolve tribes by giving citizenship, dissolve another word for disappearance, a kind of chemical word for a gradual death of tribes and Indians, a clinical killing, designed by psychopaths calling themselves politicians.”

For me, and millions of other Native Americans, the Indian CItizenship Act of 1924 became the catalyst for us becoming dual citizens — tribal citizens and citizens of the United States.

In my case, I am a proud citizen of both the Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation and of the United States. Each is governed by its own constitution. Each has its own flag. I get choked up at public gatherings when I see the Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation flag because of tremendous pride.

I cannot say the same thing about the American flag. Given the conduct of the federal government and the actions it perpetrated against Native Americans, I will admit that I have sometimes chosen to remain seated during the national anthem. I guess my allegiance stays core to my essence as a tribal citizen.

I get to vote in my tribe’s elections, and also get to vote in local, state, and federal elections as a U.S. citizen. I pay taxes to the United States, though not to my tribal government.

As I reflect back on the past 100 years, I realize that the 300,000 Native Americans who were alive in 1924 were our ancestors. My grandparents, Levi and Ellen Whitepigeon, were alive then. I wonder what they would think about the fact that the Native American population has grown to more than nine million citizens who identify as American Indians and Alaska Natives in 2024.

We know the journey for Native Americans has not been easy throughout the history of the United States. There is much work that has to be done to close the gap in the areas of health disparities, poverty, high unemployment, and to eliminate voter suppression of Native Americans. We know one of the longest-serving political prisoners in the United States — 79 year old Leonard Peltier (Turtle Mountain Ojibwe) — has been incarcerated for nearly 50 years and should be freed from prison.

We are encouraged at this centennial that Deb Haaland (Pueblo of Laguna) is the secretary of the U.S. Department of the Interior, Chief Lynn Malerba (Mohegan Tribe) is treasurer of the United States, and Charles “Chuck” Sams III (Confederated Tribes of Umatilla) serves as the director of the National Parks Service.

Progress has been made during the past 100 years. But we still have much to do in order to gain parity in the United States as dual citizens.

Thayék gde nwéndëmen - We are all related.

More Stories Like This

Extending the Affordable Care Act Is a Moral Imperative for Indian CountryAll Is Fair in … War?

Why Federal Health Insurance Policy Matters to Cherokee Nation

The Absence of October's Job Report Shows Why Native American Communities Need Better Data

Tribal IDs Are Federally Recognized. ICE Agents Are Ignoring Them.

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher