- Details

- By Lindsay VanSomeren

The Sauk-Suiattle Tribe is suing Seattle City Light, a public utility company owned by the City of Seattle, claiming that a series of dams on the Skagit River are harming the Tribe's treaty-protected right to salmon. The three dams, on an eight-mile stretch of the river in the Cascade Mountains, currently provide 20% of the electricity generated by Seattle City Light, but disrupt access to 37% of the watershed where threatened salmon, steelhead, and trout live and spawn.

The Tribe has filed three lawsuits, part of a comprehensive legal strategy to force Seattle City Light to stop its current marketing, recognize and respect the inherent rights of salmon, and ultimately, to install fish passageways at the Skagit River Hydroelectric Project’s three dams.

"Even though it sucks to get into any kind of lawsuit, it was just absolutely necessary," says Nino Maltos II, the chairman of the Sauk-Suiattle Tribe. "We just felt that it was time that we did something, and we stood up to Seattle City Light to get these fish passages put in to protect the salmon."

Want more Native News? Get the free daily newsletter today.

The first lawsuit, initially filed in Skagit County Superior Court in June 2021, is based on Washington state law that requires fish passages to be built where dams block the natural movement of migratory salmon, steelhead, and trout.

The case was moved to federal court, where it was dismissed in December 2021. The judge cited several reasons, including that the Sauk-Suiattle Tribe had agreed to a settlement allowing the dams to be relicensed in 1995, and that the current Federal Energy Regulatory Commission relicensing process or an appeals court would be a more appropriate venue for bringing up these issues. The Tribe is currently appealing this decision in the U.S. Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals.

The second lawsuit was filed in King County Superior Court in September 2021. It accuses Seattle City Light of deceptive business practices by improperly claiming that it was certified by the Low Impact Hydropower Institute (LIHI), and that it has been falsely marketing itself as the "nation's greenest utility." It has been scheduled for trial on September 19.

In 2003, when Seattle City Light applied for LIHI certification, it had to show that migratory fish didn't normally go upstream past any of the dams, otherwise fish passages would have to be built. At the time, Stillwater Science, an independent reviewer of the application, recommended that the dams not be certified because fish had historically made it past the Gorge dam, the furthest downstream of the three, but could not do so any longer.

LIHI executive director Lydia Grimm disagreed, saying in a report that a study from 1921, before the dam was built, "carries more weight," even though "there are indeed 'historical records' of anadromous fish movement through the area." (Anadromous fish are fish that migrate from the ocean up rivers to spawn.) Grimm stated that while some fish made it past the first dam, it likely wasn't enough to warrant denying the application, and so she overruled the reviewers to approve it. The dams then became the largest LIHI-approved dam project in the world.

The third lawsuit, filed in Sauk-Suiattle Tribal Court in January 2022, asks for a declaratory judgment recognizing the inherent rights of salmon. "We've been going into foreign courts which aren't always the friendliest forum for Tribal people and treaty rights. Let's take them into our court and apply our laws to them, because they have come into our territory," said Jack Fiander, the attorney representing the Sauk-Suiattle Tribe. "In part, that case is a way of educating the public and outside governments of what the Tribe's customs and traditions and unwritten laws are."

Seattle City Light has hired K & L Gates, an international law firm with offices in Seattle, to fight all three lawsuits. On February 7, the utility also filed a countersuit in federal court against the Sauk-Suiattle Tribe. It is seeking an injunction to stop the Tribe's third lawsuit from moving forward, preventing any new lawsuits from being launched in Tribal court, and also monetary damages to pay for attorney fees.

If the third lawsuit is successful, this legal strategy would allow Sauk-Suiattle Tribal citizens to sue on behalf of the salmon. The case is similar to how the White Earth Band of Chippewa Indians is suing the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources (MDNR) on behalf of manoomin, wild rice.

Indeed, that very case inspired the legal strategy of the Sauk-Suiattle Tribe, says Fiander. And similarly, MDNR responded by suing the White Earth Chippewa in federal court to challenge their authority to regulate off-reservation activity. The judge dismissed the department’s lawsuit. It is currently appealing that ruling, with a decision expected any day now.

"Other Tribes throughout the country, including in Alaska, are watching this case to see what happens because a lot of Tribes are considering, or have already adopted rights of nature laws," says Professor Hillary Hoffmann, an expert in environmental and federal Indian law at the Vermont School of Law.

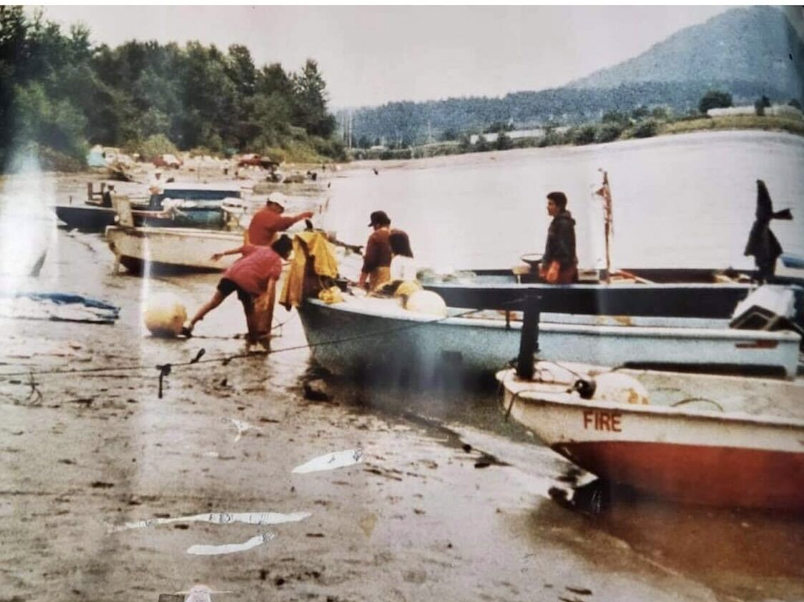

Sauk Camp on the Skagit River in the 1990s, in Mount Vernon, Washington. These are some of the waters the Tribe is seeking to protect now. (Photo Courtesy Nino Maltos Jr.)A central issue in each of the three Sauk-Suiattle cases is whether or not the three dams are, in fact, blocking access for migratory salmon, steelhead, and trout. "We were really upset that they didn't reach out to our ancestors and ask them, because we definitely believe they would have told them 'yes, the fish absolutely run through here and we don't want these dams here unless you're going to put [in] ways for the fish to make it,'" says Maltos. Construction on the dams — Gorge, Diablo, and Ross — began in 1919. The first one, Gorge, began generating power in 1924, and the last one, Ross, was completed in 1952.

Sauk Camp on the Skagit River in the 1990s, in Mount Vernon, Washington. These are some of the waters the Tribe is seeking to protect now. (Photo Courtesy Nino Maltos Jr.)A central issue in each of the three Sauk-Suiattle cases is whether or not the three dams are, in fact, blocking access for migratory salmon, steelhead, and trout. "We were really upset that they didn't reach out to our ancestors and ask them, because we definitely believe they would have told them 'yes, the fish absolutely run through here and we don't want these dams here unless you're going to put [in] ways for the fish to make it,'" says Maltos. Construction on the dams — Gorge, Diablo, and Ross — began in 1919. The first one, Gorge, began generating power in 1924, and the last one, Ross, was completed in 1952.

Both sides have evidence to point to in order to argue that fish did or did not make it above where the dams are. Sauk-Suiattle oral history states that there were migratory fish above the dams, but the Tribe is backed up by plenty of regulatory and scientific agencies involved in the FERC relicensing as well.

"No such barrier exists" to salmon and steelhead migrating through the area before the dams were built, said one early National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) comment on the FERC relicensing. "A 1915 survey of the Skagit River (USGS 1915) found no evidence of a passage barrier," the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service said in another comment.

"The Skagit River Hydroelectric Project obstructs upstream and downstream passage for several species of interest thereby limiting the potential productivity of the basin," the Washington Department of Fish and Game said in another comment. According to the National Park Service, "access to tributary and headwater habitats above dams, including in the Skagit River, are major strategies for the recovery of these Endangered Species Act (ESA)-listed species."

Regardless of whatever Seattle City Light might have said in the past, "we acknowledge that there were steelhead and chinook that likely made it as far as to Stetattle Creek, almost to Diablo Dam. We still maintain that anadromous fish did not make it beyond Diablo Dam," the second of the three dams, says Chris Townsend, Seattle City Light’s director of natural resources and hydro licensing.

"I would like to emphasize, we have in writing that we will do whatever fish passage is required by the agencies with authority to require it," says Townsend. "Now I say that because even if we wanted to do what a Tribe was requesting of us, in relation to fish passage over all three of the dams, we cannot legally do it unless the agencies with authority tell us we can."

The ultimate decision about whether fish-passage devices are put in or not rests with regulatory agencies such as NOAA and the Fish and Wildlife Service. As one of the first steps in the FERC relicensing process, Seattle City Light gathered dozens of stakeholder groups, including other Tribes in the area such as the Swinomish Tribe and Upper Skagit Tribe, to decide on what studies needed to be done to support relicensing. A review panel of outside experts will oversee the research results, but the bulk of the studies and on-the-ground work will be funded by Seattle City Light.

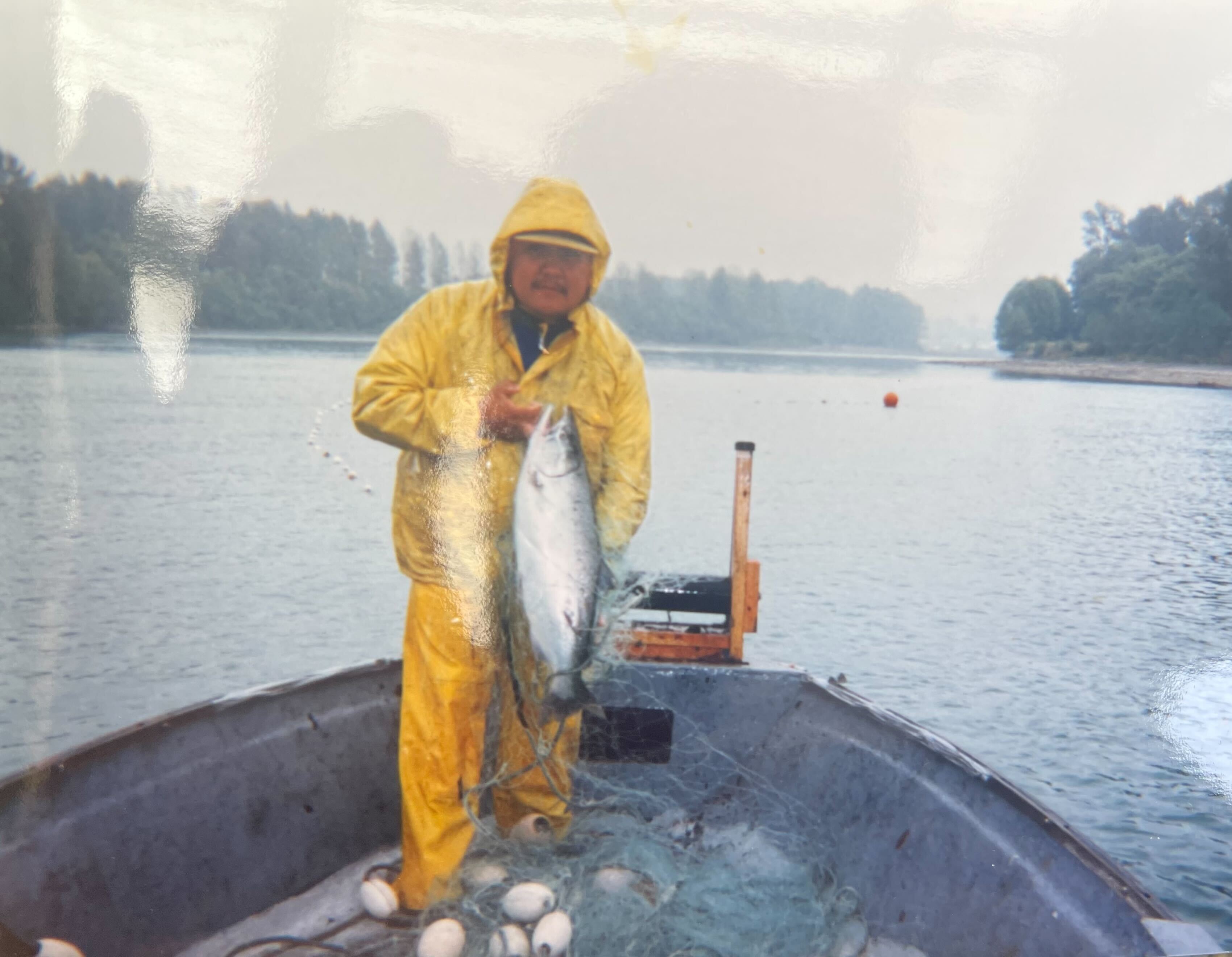

Nino Maltos Sr. fishing on the Skagit River in the 1990s. (Photo Courtesy Nino Maltos Jr.)While the Sauk-Suiattle Tribe is only advocating for fish passage to be installed at the dams, there are others in the area calling for the complete removal of the dams. Janelle Schuyler, a young member of the Upper Skagit Indian Tribe, launched a petition to remove the Gorge Dam entirely. As of Feb. 15, the petition had nearly 50,000 signatures.

Nino Maltos Sr. fishing on the Skagit River in the 1990s. (Photo Courtesy Nino Maltos Jr.)While the Sauk-Suiattle Tribe is only advocating for fish passage to be installed at the dams, there are others in the area calling for the complete removal of the dams. Janelle Schuyler, a young member of the Upper Skagit Indian Tribe, launched a petition to remove the Gorge Dam entirely. As of Feb. 15, the petition had nearly 50,000 signatures.

While the Tribes are fighting for fish passages, dams, in general, do have other impacts on the ecosystem. They prevent the downstream flow of sediment, logs, and other river material that forms habitat for salmon and other animals, and can alter temperatures throughout the watershed.

Seattle City Light will be releasing initial reports about whether fish passages are warranted in the upcoming months. If it doesn't go the way the Sauk-Suiattle Tribe hopes for, the lawsuits could be an alternate way to force the utility’s hand, says Hoffman.

"Our Tribe really hopes that Seattle City Light will finally just acknowledge that there is an impact here, and it is a potential source of the decline of the fish runs," says Maltos. "And we definitely hope that they will fix this, that they will do everything in their ability to put these fish passages in. If that were to happen, we truly believe that these runs will increase over the next 10 to 20 years."

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher