- Details

- By Edward Simon Cruz, Special to Native News Online

WASHINGTON — Power outages regularly disrupt school in Arizona’s White Mountain Apache Tribe, leading to spoiled food, limited access to technology and cold classrooms. School administrators sometimes heat buildings with kerosene. In some cases, they must close the school when carbon monoxide levels become too high.

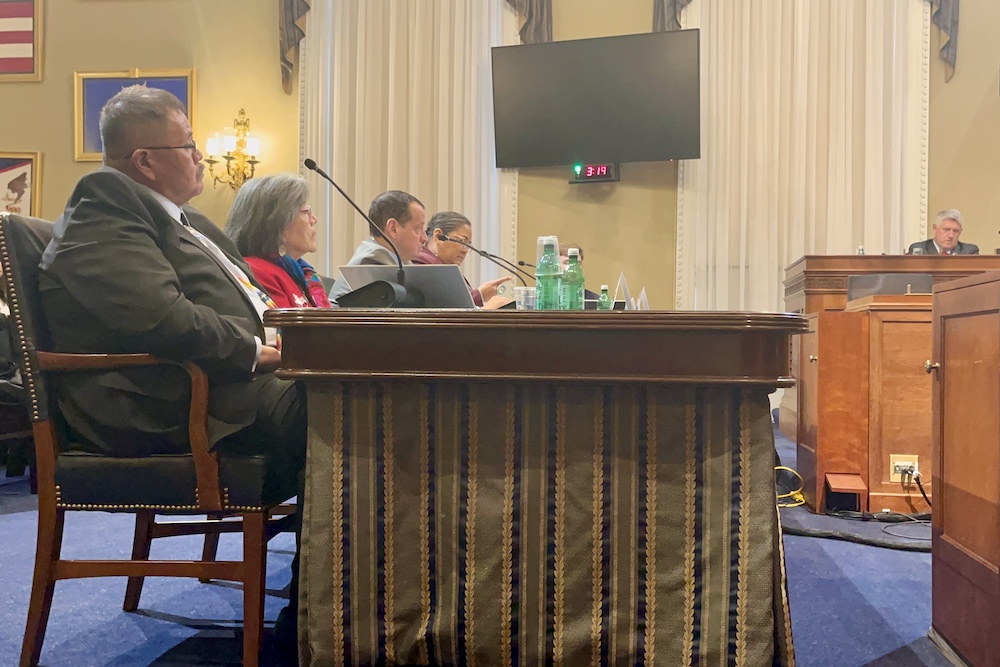

“Our students need and deserve better, and I hope you will help us deliver on the tremendous promise these young people possess,” White Mountain Apache Tribal Chairman Kasey Velasquez told congressional leaders at a Feb. 12 oversight hearing.

During the House Natural Resources Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations hearing, tribal education leaders told congressional members that the Bureau of Indian Education (BIE) schools face crumbling infrastructure, unsafe conditions and a massive backlog of deferred maintenance, while receiving less than half the per-student funding of other federally operated schools.

The 183 schools run by BIE have collectively accumulated more than $1 billion in overdue repairs as of September 2022, according to testimony shared by Rep. Bruce Westerman (R-Ariz.) during the hearing. Many maintenance requests have remained unaddressed for years.

Government inspectors recently observed a crumbling foundation and an inoperable boiler at separate schools in the same Arizona town, despite work orders dating back to 2008. About 1,000 orders placed in 2000 remained unaddressed over two decades later, including requests for exit signs, fire alarm systems and replacements for asbestos floor tiles.

“How can we expect BIE students to excel when their classrooms are crumbling around them,” Westerman said.

The delays in addressing maintenance issues distract students from learning, members of Congress and tribal leaders agreed.

“Delays mean an inability to feed children because of spoiled food in the broken refrigerators. Delays mean students struggling to focus as rainwater leaks into their classroom,” said Rep. Paul Gosar (R-Ariz.), chair of the House Natural Resources Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations.

A 2021 report from Stanford University, The Arizona Republic and ProPublica found that students in bureau-run schools score below the national average on standardized tests by more than two grade levels.

Several Indigenous leaders requested that the federal government transfer control over buildings, replacements and repairs to tribes under the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975.

Jason Dropik, executive director of the National Indian Education Association, said tribal control of federal funding to run the schools themselves would help “eliminate some of that red tape.” Dropik, a member of the Bad River Band of Lake Superior Chippewa Indians, asked to increase funding from the Great American Outdoors Act and implement advance appropriations to address the backlog of deferred maintenance orders.

For the 2023-24 school year, the Interior Department projected spending about $6,900 per student in BIE schools. Conversely, the Defense Department said in 2023 that it spent about $25,000 per student in the Department of Defense Education Activity, the only other federally operated school system.

Rep. Maxine Dexter (D-Ore.) noted that none of the tribes at the hearing received more money for their schools after similar congressional testimonies in the past. She criticized Senate Republicans for seeking to decrease federal funding for tribal schools.

“We can’t fix an underfunding problem by further underfunding,” Dexter said.

Since 2013, the BIE has implemented the Government Accountability Office’s recommendations for school safety and construction, including conducting annual inspections at all buildings. However, Melissa Emrey-Arras, director of GAO’s education, workforce and income security team, said the bureau still lacks clear procedures for other key issues, like training special education staff or monitoring certain financial transactions.

Roy Tracy, interim superintendent of schools at the Department of Diné Education in the Navajo Nation, said the bureau’s changes in the last decade fail to fully compensate for over a century of failed policies for Indigenous schools. He praised the tribal leaders who sat before Congress and demanded more direct financial support for their nations.

“Empower us,” he said. “Trust us. Pass that funding along.”

Edward Simon Cruz is an education reporter in Washington, D.C. for the Medill News Service.

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher