- Details

- By Jenna Kunze

The University of Alabama Museums have skeletons in their closets—literally.

For the past decade, the seven Muskogean language-speaking tribes who originally resided in what is now Alabama have sought the return of an estimated 5,892 human remains—their ancestors—and the artifacts buried with them from the University of Alabama. The university owns an archaeological park, called Moundville, where the remains were excavated from.

“Basically what it boils down to is that the University of Alabama has in its possession thousands of our ancestors that were from the Southeastern original homeland Muscogee Creek People, and other tribes as well,” Muscogee Nation spokesperson Jason Salsman told Native News Online. The six other tribes are the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, the Chickasaw Nation, the Coushatta Tribe of Louisiana, Alabama-Quassarte Tribal Town, the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, and the Seminole Tribe of Florida. Throughout the 1800s and early 1900s, settlers pushed these tribes out of their homelands to Oklahoma, Texas, and Louisiana.

“This repatriation fight has been going on, in our minds, long enough,” Salsman said.

Want more Native News? Get the free daily newsletter today.

For years, the University of Alabama has said it is willing to consult with the tribes, but it questioned the cultural affiliation or the links between the human remains it possesses and present-day tribes. It also said it would not return the funerary objects, which are currently on display at its museum, according to testimony from the tribes.

In 1990, Congress passed the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA). It requires federal agencies and museums receiving federal funds to take an inventory of Native American human remains and funerary objects they hold; consult with the tribes about what to do with them; and generally give the lineal descendants or culturally affiliated tribes the right to make the final determination about what to do with them, such as reburial or long-term curation.

But a loophole in the law allowed the majority of the remains catalogued—those without documented tribal affiliation, deemed “culturally unidentifiable”—to fall through the cracks. Though museums and agencies still had to report those remains, there was no timeline or requirement for a museum to identify their cultural affiliation. In the 1990s, the University of Alabama listed the remains from Moundville as culturally unidentifiable.

On November 24, a federal committee that oversees NAGPRA made clear the cultural connection for the descendants of Moundville.

In response to a petition filed jointly by the seven tribes, the NAGPRA Review Committee found a "preponderance of the evidence for cultural affiliation" between the seven Muskogean language-speaking tribes and the human remains and cultural objects found at the Moundville Archaeological Park. Members of the review committee called the 117-page document provided by the tribes “a strong case” with “overwhelming evidence.”

The tribes spent a year preparing its claim for the committee, including linguistic evidence, geographical evidence, oral traditions, kinship, biological, historical, and anthropological evidence.

“Going far beyond preponderance, the evidence presented in this claim establishes beyond any reasonable doubt that the Muskogean-speaking Tribes are culturally affiliated with the Moundville archaeological site,” the claim reads. “Moundville is at least as closely affiliated with the Muskogean-speaking Tribes as Plymouth Colony is to the United States. Moundville is at least as important to our identities and contemporary communities as Plymouth Colony is to the United States.”

The Muscogee Nation’s tribal historic preservation officer, RaeLynn Butler, said she’s happy with the outcome, but overwhelmed when she thinks about the ancestors whose remains are still in museum closets, such as at the University of Alabama’s other location holding collections, the Office of Archaeological Research.

“I don't think the university was ever upfront with how many skeletons that were in their closet,” Butler told Native News Online.

According to documents from tribal visits to the museum — specifically one in 2016, in a consultation where, according to the claim, the university wanted to demonstrate how well it was caring for the Tennessee Valley Authority’s collection — human remains were kept in plastic bags in five-gallon buckets on the floor, brown paper bags “with burial fill spilling out,” and cardboard boxes “with gaping holes in the sides.”

“For people to know that it's almost 6,000 [remains] I think that that's overwhelming,” Butler said. “And that they've had them for almost 80 years? I think anyone who is new to this would be shocked, and should be shocked. Because what's the need to keep them? And what have [they] been doing with them?”

According to Butler, the university has used the Moundville ancestors and their funerary objects for over 200 publications and studies, although last year, it instituted a moratorium on research studying the ancestors.

In the 2016 visit to examine the TVA collection, tribal observers noted that images of funerary objects were being displayed on desktop computers' screensavers.

“It's a night-and-day difference on how they curate the human remains, versus how they curate the funerary objects, which have their own shelf and have a very secure facility that only four people have access to,” Butler said. “They have certain styrofoam and different things around them to make sure they don't wobble or fall, versus having 200 people on one shelf in brown paper sacks.”

The tribes are waiting for the university’s response.

In a letter sent to the tribes on Nov. 19 obtained by Native News Online, university executive vice president James Dalton wrote that “The University of Alabama seeks to consult and acknowledge the joint claim for human remains and funerary objects from the Muskogean-speaking tribes to the Moundville site and associated sites in Tuscaloosa and Hale Counties, Alabama. The University will provide a more detailed response to you in the coming days outlining our thoughts on the most productive and efficient manner to address the pending joint request through the consultation process.”

University spokesperson Monica Watts told Native News Online that the university had sent the letter to the seven tribes “requesting consultation begin,” but had “received no acknowledgement from the tribes.” She was referring to the letter where Dalton told the tribes to wait for a more detailed response “in the coming days.”

Watts also noted that the university was not “invited to participate” in the NAGPRA oversight committee meeting, and that “any decision was made solely on information presented by the requesting tribes.”

But the committee’s procedural rules do not state that all affected parties must be present.

According to federal policy for the NAGPRA review committee’s finding-of-fact procedure, the seven tribes’ request was in line with the law, “where the requesting Indian tribe… can show cultural affiliation by a preponderance of the evidence based upon geographical, kinship, biological, archaeological, anthropological, linguistic, folkloric, oral traditional, historical, or other relevant information or expert opinion.”

“The ball is in their court now,” Butler said. “Their letter just saying that they're going to consult isn't enough for us after six years of hearing that, because when is it going to happen? We feel our patience has been taken advantage of and where we now want action only.”

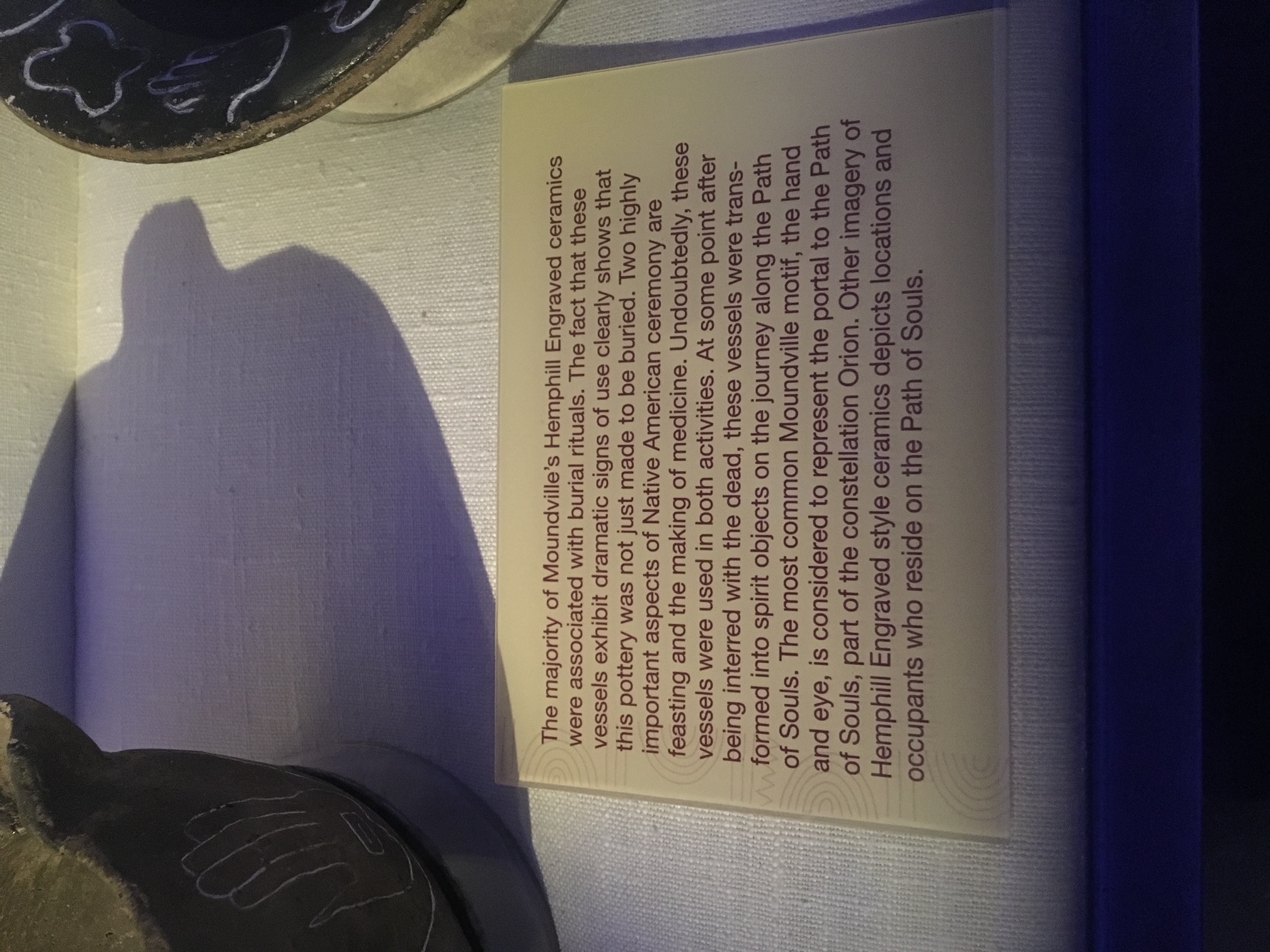

Many of the objects on display at the Moundville Archaeological Park Museum are burial objects that were buried with ancestors. It is culturally inappropriate for burial items to be photographed or on display. (Photo Courtesy RaeLynn Butler)

Many of the objects on display at the Moundville Archaeological Park Museum are burial objects that were buried with ancestors. It is culturally inappropriate for burial items to be photographed or on display. (Photo Courtesy RaeLynn Butler)

More Stories Like This

Native News Weekly (August 25, 2024): D.C. BriefsUS Presidents in Their Own Words Concerning American Indians

Native News Weekly (August 4, 2024): D.C. Briefs

WAPO's Dana Hedgpeth Selected as 2025 IJA-Medill Milestone Achievement Award Winner

US Court of Appeals Deals Setback for Native American Voting Rights

Help us tell the stories that could save Native languages and food traditions

At a critical moment for Indian Country, Native News Online is embarking on our most ambitious reporting project yet: "Cultivating Culture," a three-year investigation into two forces shaping Native community survival—food sovereignty and language revitalization.

The devastating impact of COVID-19 accelerated the loss of Native elders and with them, irreplaceable cultural knowledge. Yet across tribal communities, innovative leaders are fighting back, reclaiming traditional food systems and breathing new life into Native languages. These aren't just cultural preservation efforts—they're powerful pathways to community health, healing, and resilience.

Our dedicated reporting team will spend three years documenting these stories through on-the-ground reporting in 18 tribal communities, producing over 200 in-depth stories, 18 podcast episodes, and multimedia content that amplifies Indigenous voices. We'll show policymakers, funders, and allies how cultural restoration directly impacts physical and mental wellness while celebrating successful models of sovereignty and self-determination.

This isn't corporate media parachuting into Indian Country for a quick story. This is sustained, relationship-based journalism by Native reporters who understand these communities. It's "Warrior Journalism"—fearless reporting that serves the 5.5 million readers who depend on us for news that mainstream media often ignores.

We need your help right now. While we've secured partial funding, we're still $450,000 short of our three-year budget. Our immediate goal is $25,000 this month to keep this critical work moving forward—funding reporter salaries, travel to remote communities, photography, and the deep reporting these stories deserve.

Every dollar directly supports Indigenous journalists telling Indigenous stories. Whether it's $5 or $50, your contribution ensures these vital narratives of resilience, innovation, and hope don't disappear into silence.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Native languages are being lost at an alarming rate. Food insecurity plagues many tribal communities. But solutions are emerging, and these stories need to be told.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Native languages are being lost at an alarming rate. Food insecurity plagues many tribal communities. But solutions are emerging, and these stories need to be told.

Support independent Native journalism. Fund the stories that matter.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher