- Details

- By Levi Rickert and Neely Bardwell

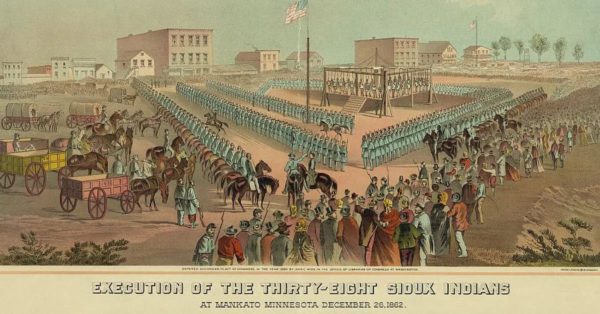

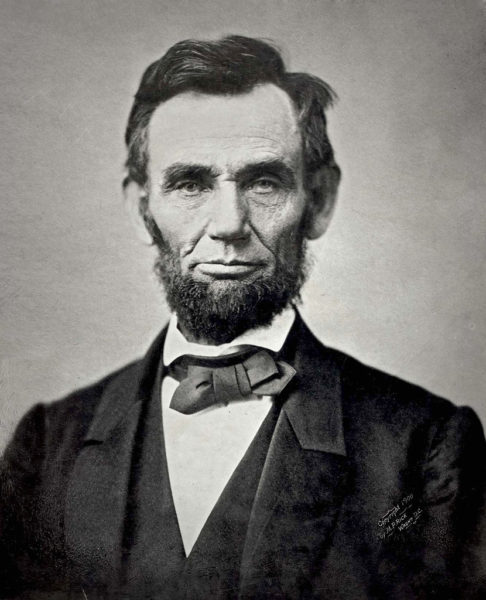

This Day in History: Dec. 26, 1862 —Most commonly revered as the United States President who freed the slaves, Abraham Lincoln is known for something different in Indian Country. On this day 160 years ago, 38 Dakota men were hanged following orders from Lincoln in the largest mass-hanging in U.S. history.

The execution happened in Mankato, Minnesota in front of some 4,000 spectators. Some historical accounts say that the men each held hands and sang a traditional Dakota song in the moments leading up to their deaths.

Often erased from history, the men’s hangings were direct consequences of the U.S. and Dakota War of 1862. The war was the result of broken treaties and broken promises from the U.S. government after Dakota land continued to be diminished.

The war lasted for over 37 days and resulted in the deaths of an estimated 77 U.S. soldiers and 29 Dakota warriors. The U.S. took more than 2,000 Dakota leaders into custody where many were eventually sentenced to prison, and others to death.

Lincoln ended up only approving the execution of Dakota leaders who were proven to have committed civilian massacres. While the 38 men approved for execution were awaiting their demise, 3,000 other tribal members and prisoners were being sent to Fort Snelling.

American Indian author Mark Charles wrote for Native News Online:

In the fall of 1862, after the United States failed to meet its treaty obligations with the Dakota people, several Dakota warriors raided an American settlement, killed five settlers and stole some food. This began a period of armed conflict between some of the Dakota people, the settlers, and the US Military. After more than a month, several hundred of the Dakota warriors surrendered and the rest fled north to what is now Canada. Those who surrendered were quickly tried in military tribunals, and 303 of them were condemned to death.

The trials of the Dakota were conducted unfairly in a variety of ways. The evidence was sparse, the tribunal was biased, the defendants were unrepresented in unfamiliar proceedings conducted in a foreign language, and authority for convening the tribunal was lacking. More fundamentally, neither the Military Commission nor the reviewing authorities recognized that they were dealing with the aftermath of a war fought with a sovereign nation and that the men who surrendered were entitled to treatment in accordance with that status. (Carol Chomsky)

Because these were military trials, the executions had to be ordered by the President Abraham Lincoln.

Three hundred and three deaths seemed too genocidal for President Lincoln. But he didn’t order retrials, even though it has been argued that the trials which took place were a legal sham. Instead he simply modified the criteria of what charges warranted a death sentence. Under his new criteria, only two of the Dakota warriors were sentenced to die. That small number seemed too lenient, and President Lincoln was concerned about an uprising by his white American settlers in that area. So for a second time, instead of ordering retrials he merely changed the criteria of what warranted a death sentence. Ultimately, 39 Dakota men were sentenced to die.

And on December 26, 1862, by order of President Lincoln, and with nearly 4,000 white American settlers looking on, the largest mass execution in the history of the United States took place. The hanging of the Dakota 38.

The New York Times provides a haunting recount of the day’s events:

Precisely at the time announced — 10 A.M. — a company, without arms, entered the prisoners’ quarters to escort them to their doom. Instead of any shrinking or resistance, all were ready, and even seemed eager to meet their fate. Rudely they jostled against each other, as they rushed from the doorway, ran the gauntlet of the troops, and clambered up the steps to the treacherous drop.

As they came up and reached the platform, they filed right and left, and each one took his position as though they had rehearsed the programme. Standing round the platform, they formed a square, and each one was directly under the fatal noose. Their caps were now drawn over their eyes, and the halter placed about their necks. Several of them feeling uncomfortable, made severe efforts to loosen the rope, and some, after the most dreadful contortions, partially succeeded.

The signal to cut the rope was three taps of the drum. All things being ready, the first tap was given, when the poor wretches made such frantic efforts to grasp each other’s hands, that it was agony to behold them. Each one shouted out his name, that his comrades might know he was there. The second tap resounded on the air. The vast multitude were breathless with the awful surroundings of this solemn occasion. Again the doleful tap breaks on the stillness of the scene.

Click! goes the sharp ax, and the descending platform leaves the bodies of thirty-eight human beings dangling in the air. The greater part died instantly; some few struggled violently, and one of the ropes broke, and sent its burden with a heavy, dull crash, to the platform beneath. A new rope was procured, and the body again swung up to its place. It was an awful sight to behold. Thirty-eight human beings suspended in the air, on the bank of the beautiful Minnesota; above, the smiling, clear, blue sky; beneath and around, the silent thousands, hushed to a deathly silence by the chilling scene before them, while the bayonets bristling in the sunlight added to the importance of the occasion.

In a separate historic order, Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation, which freed the slaves, went into effect six days later on Jan. 1, 1863.

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher