WINDOW ROCK - He always mentioned frybread and mutton stew.

Originally published in the Navajo Times.

And he always asked what new progress the Navajo Tribe has made in the past 30-plus years, said Lenny Foster, a retired supervisor for the Navajo Nation Corrections Project.

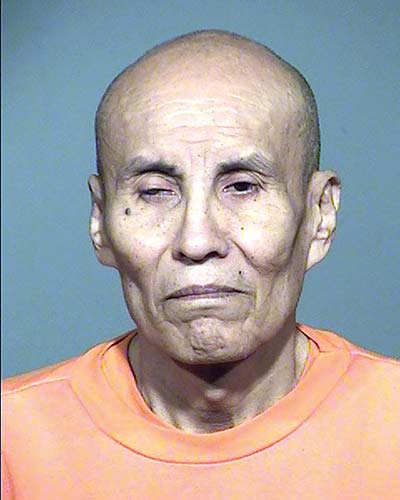

Foster spoke of Clarence Wayne Dixon, the condemned 66-year-old Navajo man from Fort Defiance, with whom he had one of his last spiritual counseling conversations.

“He’s asking what’s some of the new progress have been made, the roads, any business development, or if the Navajo government has been progressing,” Foster said on Mother’s Day.

Foster said he’d been counseling Dixon, who was executed Wednesday morning for the 1978 rape and murder of Arizona State University student Deana Bowdoin.

Longing for home

“I’ve been counseling him once a week since March for 45 minutes,” Foster said.

He said he would not be performing a sweat-lodge ceremony with Dixon, adding, “We’ll just do a prayer spiritual counseling over the phone.”

The chaplain at the Arizona Department of Corrections requested Foster to counsel Dixon.

Since being asked, Foster felt he had an obligation to provide Dixon with spiritual counseling in Navajo traditional beliefs. Foster became acquainted with Dixon in 1988 at the Perryville State Prison in Goodyear, Arizona, while performing a sweat-lodge ceremony.

Being incarcerated for more than 30 years, Foster said Dixon had some recollection of the Navajo Nation. He also taught himself to speak the Navajo language, but not fluently.

He wanted to know if the Navajo people still had no running water or electricity. He also wanted to learn more about Navajo teachings, he added.

“It’s thought-provoking questions he has,” Foster said.

Most of all, Dixon liked bringing up frybread and mutton during their conversations.

“He likes to bring that up,” Foster said. “That was always a delicacy for him. He misses frybread and mutton stew. He wanted to know if there were sales or shops.”

He said he told Dixon they are sold at flea markets and restaurants.

“He’s missed out on a lot,” Foster said. “He’s been in prison for like a good 30 years.”

Aside from their talks of home, Foster said Dixon didn’t really talk about his crime. But he never asked him of it either, he added.

Timeline of crimes

Dixon, a 1974 Chinle High graduate, began his crimes in 1977.

As an Arizona State University student, he was studying engineering when he was arrested for assault with a deadly weapon after hitting a 15-year-old female over the head with a metal pipe.

Then Maricopa Superior Court Judge Sandra Day O’Connor found him not guilty because of insanity and dismissed the charges against him.

In 1978, Dixon was arrested for burglary and assault on a woman, after which he was subsequently sentenced to five years in prison.

In 1985, he was released from prison and moved to Flagstaff to live with his brother.

Three months after he was released, Dixon was arrested and charged with aggravated assault, kidnapping, sexual abuse, and four counts of sexual assault on a Northern Arizona University student.

According to court documents, he dragged the NAU student into the forest, where he forced her to engage in numerous sexual acts at knifepoint.

During his trial, Dixon fired his state-appointed attorneys and represented himself. He was found guilty and convicted and received a seven consecutive, life term prison sentence in 1987.

Eight years later, in 1995, Dixon was required to provide his DNA under the DNA Identification Act.

In 2001, the DNA collected from Dixon matched the DNA collected from Bowdoin’s body. He was indicted on one count of first-degree murder and one count of first-degree rape. In 2008, a jury found him guilty and sentenced him to die.

Death row inmate

Since becoming acquainted with Dixon, Foster said he had a “real sense of sadness, sorrow,” knowing Dixon would be executed.

“I sweated with Mr. Dixon when he was incarcerated,” said Foster of a sweat-lodge ceremony in which Dixon participated. “So, I know him that way.”

On Tuesday, Dixon’s attorney Eric Zuckerman, argued his client was incompetent to be executed to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals.

Zuckerman argued the court needed to look at Dixon’s ability to rationally understand the reasons for the state substitution of his mental illness when Appeals Judge Jay Bybee asked him if Dixon was no longer qualified to be executed because of his schizophrenia.

“I don’t see the evidence that he is delusional about the reasons for his execution,” Bybee responded to Zuckerman.

Jeff Sparks, appeals bureau chief at the Maricopa County Attorney’s Office, said Dixon was competent to be executed because “he would bring the victim back if he was capable of it,” referencing Dr. Carlos Vega, the state’s expert witness.

“The statements that support the finding of competency by the state court include the fact that he wished he was in another state that doesn’t have the death penalty because he understands he wouldn’t be executed for murder if he was in a state that didn’t have a death penalty,” Sparks told the court.

Hours later, the court denied a stay of execution. The only option left for Dixon was to appeal his case to the U.S. Supreme Court.

On Monday, Dixon’s attorneys argued the lethal injection drug, pentobarbital, had expired. The state of Arizona agreed to use new lethal injection drugs for Dixon.

Heavy burden

Foster said he felt sadness and remorse for the families.

“Indian people should not be engaged in any behavior that harms other people,” said Foster, adding Dixon’s crime was not “self-defense.”

“It wasn’t protecting your family, wasn’t protecting your home, so his behavior violated the laws of the state of Arizona,” he said of Dixon.

“Jó éí bee nantxinígíí doo bił nijinéedah nihidiʼníiłeh. Yíiyáh, báhádzid, ‘áadoo íntʼíní,’nihidiʼníiłeh ndʼę́ę́ʼ,” Foster said of Navajo teachings with which he was raised.

He also said he wondered why the younger generations seemed not to follow traditional teachings.

“Éí shį́į́ nantxinígíí tʼahandiih hólǫ́ǫ́ ndi, haaléitʼáo díí nihitséłkéí ádaatʼéhígíí doo yił danilį́ dah?” he asked.

The former supervisor for the Corrections Project said “he sensed a sense of remorse” from Dixon.

“It’s a very sad situation for him,” he said.

Deputy director for the Arizona Department of Rehabilitation and Reentry, Frank Strada, said Dixon was executed by means of lethal injection.

“Maybe I’ll see you on the other side, Deana. I don’t know you and I don’t remember you,” Dixon said as his last words at 10:19 a.m., which was shared with the press at the State Prison Complex in Florence, Arizona.

Dixon died at 10:30 a.m. Wednesday.

His last meal was Kentucky Fried Chicken, according to Foster, who talked with Dixon one last time before he died.

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher