- Details

- By Jenna Kunze

On Jan. 21, 1855, Makah villages in what is now the northwest coast of Washington made a deal with the U.S. government—a treaty—where tribal representatives ceded the title to 300,000 acres of tribal land to retain certain pre-existing rights into the future. Among them was a right to education, health care, and the explicit right to hunt seals, fish and whales.

Then, for nearly 80 years beginning in the 1920s, tribal whaling crews abstained from their cultural traditions in response to dwindling grey whale population sizes. The federal government listed the gray whale as an endangered species, but delisted it in 1994 when the group returned to healthy population sizes.

Want more Native News? Get the free daily newsletter today.

“It wasn't until the gray whale was making a comeback that we then started to pursue it,” said tribal member and cultural bearer, Polly McCarty.

In 1999, the tribe successfully hunted its first and only gray whale of the century. McCarty, 65, was partnered with the whaling crew’s harpooner at the time, and performed the accompanying female role of the hunt: “It's believed that a woman becomes one with the whale,” she said. She’d lie still on her back at home for as long as it took hunters to secure a whale— from 2 a.m. until 6 p.m. “If the woman was moving and thrashing about, the whale would do the same thing. And it would cause harm to the crew.”

The day the whale was landed—May 17, 1999—would go down in local history as “whale day,” to be celebrated each year. The beach at Neah Bay was “packed shoulder to shoulder” to celebrate the event, tribal Chairman Timothy Greene said. McCarty described the day as feeling similar to the joy of Christmas, only one hundred times stronger.

The feeling would be taken from the community for the next 20 years, held up in a legal battle and corresponding administrative process waged by conservation and animal rights groups. The lawsuit ultimately put the tribe in the legal realm of having to apply for a waiver under the Marine Mammal Protection Act, despite the explicit language of their treaty and an exemption within the MMPA for Native Americans and Alaska Natives “who (dwell) on the coast of the North Pacific Ocean or the Arctic Ocean.”

Now, over two decades later, an administrative law judge in Seattle, George Jordan, has made a non-binding recommendation that a waiver be granted to the Makah tribe allowing them to hunt three whales a year. Jordan’s recommendation will be sent to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Fisheries’ Assistant Administrator, Janet Coit, to put the waiver into effect. NOAA Fisheries is responsible for managing the nation's marine fisheries, and for conserving and protecting marine species. Jordan sent his recommended decision—based on extensive scientific research— to Coit on September 23rd. On October 18, 2021, NOAA Fisheries announced a 25-day extension to the original 20-day public comment period, with a new deadline of November 13, 2021 to receive comments.

Makah tribal chairman Timothy Greene said he’s feeling “cautiously hopeful” his tribe will soon resume its hunt. “We've been at it for 20 years,” Chairman Greene said. “I fully anticipate that there'll be some legal challenges.”

“The longer this gets drawn out, the more people that lose their opportunity,” Vice-Chairman of the Makah Tribe, Patrick DePoe, said. “And I say that because 22 years of time has passed since we've been back out on the ocean hunting these whales. Twenty-two years is a long time. People that might have been able to do this that were in their forties are now in their sixties.”

Sea Shepherd Conservation Society and the Animal Welfare Institute are the two main groups tribal members say have threatened and harassed them for their hunting practices for years, and who brought the initial lawsuit.

DePoe remembers times in high school when the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society would bring boats to the Neah Bay shoreline “and honk their horn and scream obscenities at us.” Some protesters wore shirts that read ‘Save the whale, kill the Indian,” he said.

A spokesperson from Sea Shepherd Conservation Society declined to comment.

"At no point, did AWI threaten or harass the Makah tribe," Margie Fishman, Public Relations Manager of the Animal Welfare Institute, said in an email to Native News Online.

Tribal leaders agree that the attack on the Makah Tribe was born from a lack of understanding.

“We are the first environmentalists,” McCarty said. “We were the ones who looked after the land and took care of it. We were here before they were with all their fancy money making things. I think if they took the time to understand our culture they would understand that.”

In McCarty’s family, her grandfather was the last relative to whale hunt. But from childhood, she learned about the practice by sitting around the kitchen table. It bothers her when outsiders act like the last whale hunt in 99 allowed the tribe to reconnect with their culture for the first time.

“That is so not true,” she said. “We have always been connected with our culture. Just because we didn’t actually do it, we still were taught. Otherwise, how would we know?”

The real tragedy, as many see it, is in the impact that the continued delay has had on community members.

Waiting for the U.S. Government to Acknowledge its own Treaty

Until the waiver is officially granted, the U.S. government is not living up to its treaty responsibility, says Greene. In other words, it is breaking its own law.

Tribal leaders say that the administrative law judge’s recommendation comes with rigorous research and backup from federal agencies, so it's all but ensured it will be granted. Still, the process has been detrimental for the Makah tribe.

“It shouldn't take this long, and there's got to be some reasonableness in the process,” Greene said. “Especially when you're talking about an agreed upon right or reserved right, that we've bought and paid for. It’s detrimental to our... spiritual health, to our physical health. Those impacts are things that …(are) hard to measure through this type of system.”

Even with the pending treaty recognition, Makah Cultural and Research Center director Janine Ledford called the recommended hunting “take” limit of three whales a year “a measured recognition of (Makah’s) treaty rights.”

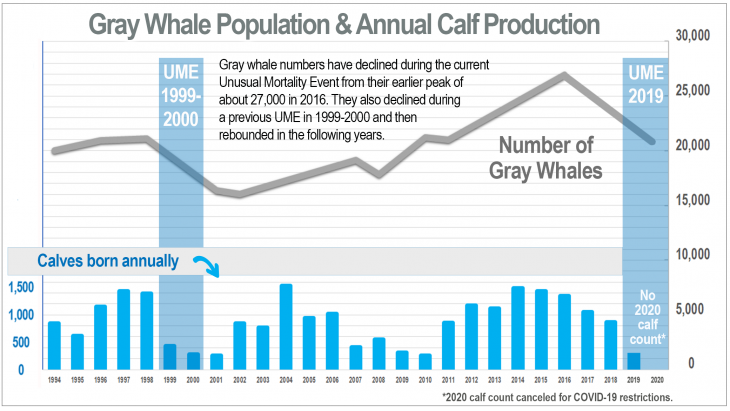

The latest Eastern North Pacific gray whale population estimate via NOAA. The graphic shows a recent estimate of 20,580 whales, down from the earlier peak of about 27,000 whales.

The latest Eastern North Pacific gray whale population estimate via NOAA. The graphic shows a recent estimate of 20,580 whales, down from the earlier peak of about 27,000 whales.

The three is sufficient for now, Chairman Greene said, though he imagines the need will grow in the future and require permit adjustment. The Eastern North Pacific gray whale population has been gradually growing in size since it was officially delisted as an endangered species in 1994. Now, NOAA Fisheries estimates the species population to number roughly 20,580 whales.

According to the administrative law judge who issued the recent recommendation: “NMFS (or NOAA Fisheries) considered the best available scientific evidence in determining that the hunt is unlikely to have a negative effect on the ENP (Eastern North Pacific) stock as a whole.”

For McCarty, the potential waiver presents a necessary step forward.

“We have to do whatever it takes to jump through all the hoops legally so that our children will be able to (hunt) on a yearly basis so they can feed the people,” she said. “You’re going to feed them physically, but also you’re going to feed them mentally, spiritually. I think that’s important.”

This article has been updated to include a quote from the Animal Welfare Institute.

More Stories Like This

Native News Weekly (August 25, 2024): D.C. BriefsUS Presidents in Their Own Words Concerning American Indians

Flanagan Calls ICE Agents ‘out of control’ after Woman Killed in Minneapolis

American Indigenous Tourism Association Announces New Board Members

Deb Haaland Talks Youth, Jobs and Opportunity in Governor Bid

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher