- Details

- By Jenna Kunze

United States Department of the Interior (DOI) Secretary Deb Haaland and Assistant Secretary for Indian Affairs Bryan Newland got emotional this afternoon in a press conference announcing the findings of the Federal Indian Boarding School investigation.

The 106-page report—penned by Newland and released to the public at noon on Wednesday, May 11—details for the first time that the federal government operated or supported 408 boarding schools across 37 states between the years 1819 and 1969. Additionally, the investigation identified 53 marked and unmarked burial sites connected to the schools, though the Department expects to find the number of children buried at boarding schools across the nation to be in the “thousands or tens of thousands,” as the investigation continues.

“Each of those children is a missing family member, a person who was not able to live out their purpose on this earth because they lost their lives as part of this terrible system,” Haaland said during the press conference. “This is not news to us. As Indigenous people, we have lived with the intergenerational trauma of federal Indian boarding school policies for many years. But what is new is the determination in the Biden-Harris administration to make a lasting difference in the impact of this trauma for future generations.”

As a result of the report—which will lead to a continued investigation to uncover burial sites associated with each boarding school, as well as the names and identities of the children buried there—Haaland announced a yearlong cross-country tour called “The Road to Healing” to connect with and listen to boarding school survivors’ stories.

“Recognizing the impacts of the federal Indian boarding school system cannot just be a historical reckoning,” Haaland said. “We must also chart a path forward to deal with these legacy issues.”

Each speaker at the press conference stressed the living, present-day impacts that boarding schools continue to have on Native communities.

Newland, who paused several times to choke back emotions, spoke about the need for “an independent research group” to assess the lasting impacts federal Indian boarding schools have had on Native health, education, and economic status.

“There's not a single American Indian, Alaskan Native, or Native Hawaiian in this country whose life hasn't been affected by these schools,” Newland said. “That impact continues to influence the lives of countless families, from the breakup of families and tribal nations, to the loss of languages and cultural practices and relatives. We haven't begun to explain the scope of this policy aea until now.”

Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition (NABS) Director Deborah Parker said that the report’s publication signifies a historic moment in American history, “as it reaffirms the stories we all grew up with, the truth of our people, and the often immense torture our elders and ancestors went through as children at the hands of the federal government and the religious institutions.”

Parker said that investigation is needed beyond the DOI’s work “to know the magnitude of loss and human life.” She petitioned for the passage of the Truth and Healing Commission on Indian Boarding School Policies Act that would build on the work of the Interior Department.

Importantly, the bill would task a Truth and Reconciliation Commission with locating and analyzing all records on Indian boarding schools, including church and government records beyond the Department of Interior's reach.

The bill will have a live hearing with the House Natural Resource Subcommittee for Indigenous Peoples tomorrow at 1pm. Tribal leaders and survivors, including Parker, are expected to give testimony in support of the legislation.

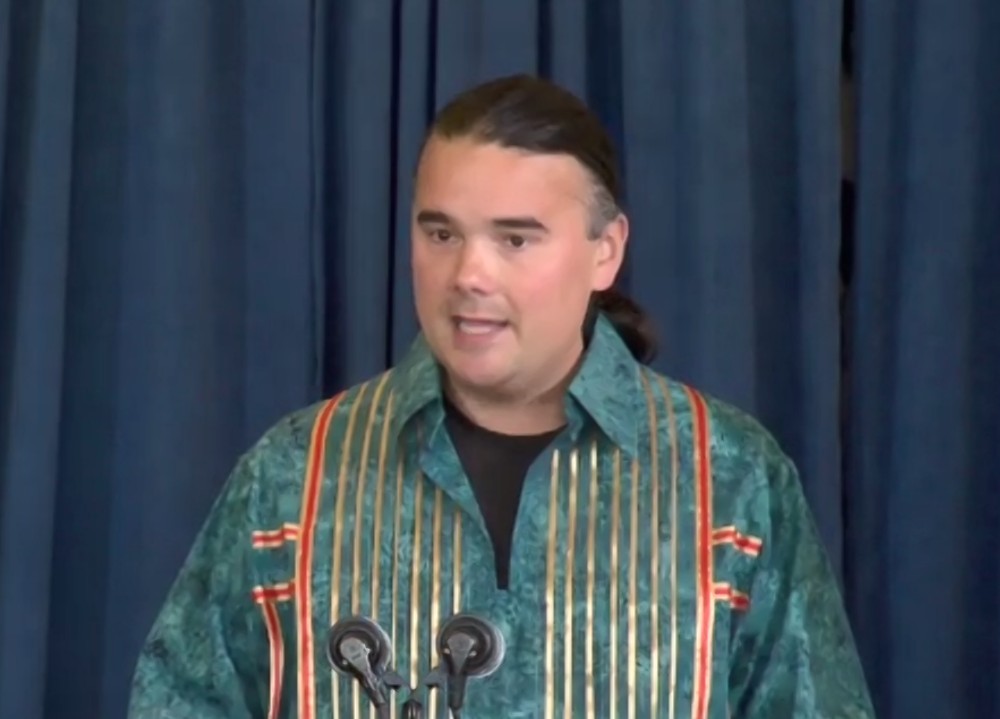

Jim LaBelle Sr., an Alaska Native survivor of boarding schools from ages eight to 18 years old, also addressed the press on Wednesday afternoon.

“I learned everything about European American culture—its history, language, civilizations, math, science—but I didn't know anything about who I was as a Native person,” LaBelle said. “I came out not knowing who I was.”

LaBelle credited the boarding school era for the vast over-representations of Alaska Natives who have been incarcerated or lived in foster care in the state.

In response to a question about whether reparations are owed to boarding school survivors, LaBelle said that “it's going to require some sort of resources to help put our languages back together, rescind federal (initiatives) that restrict us from traditional hunting, fishing and gathering, and (take) another look at our criminal justice system.”

Currently, the federal Bureau of Indian Education funds or operates 186 schools across the United States, including four off-reservation boarding schools.

Another reporter asked what the transformation between the schools that exist right now and those run by the Bureau of Indian Affairs in the past.

“The most important thing to understand right now is that it is not the express purpose of the United States federal government to operate the schools to forcibly assimilate kids,” Newland said, adding that most of the schools funded by the Bureau of Indian Affairs are operated directly by tribes. “So the difference is at the core of the school's mission, which is to empower Indian kids in their communities… and not to forcibly assimilate kids and not to take them from their families without their consent.”

In response to whether or not the federal investigation will include any religious schools Native American children attended that predated 1819, Newland said that DOI is “really focusing on [its] role as the United States federal government.”

“I think it’s really important because of our sacred trust relationship with tribes and with Indian people that we account for our actions,” Newland said.

Haaland and Newland both stressed that the report published today is merely the first step of the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative.

“There's a lot more work that has to be done to simply tell the truth and lay out the scope of the federal Indian boarding school system,” Newland said. “There are survivors and families and communities that want to come forward to tell their story. So in short, there's a lot of work left to do to simply get to this point where we can explain for ourselves on behalf of the United States federal government, what we did with these boarding schools.”

The next step of the investigation will be to focus on numbering how many kids were placed in federal Indian boarding schools across the country, how many kids didn't make it home, where they're buried, and counting how many federal dollars were spent operating the boarding school system.

Tell Us What You Think

More Stories Like This

Native News Weekly (August 25, 2024): D.C. BriefsUS Presidents in Their Own Words Concerning American Indians

Deb Haaland Tours CNM Workforce Facilities, Highlights Trade Job Opportunities

Federal Court Dismisses Challenge to NY Indigenous Mascot Ban

Sen. Angus King Warns of ‘Whitewashing’ History in National Parks Under Trump Administration

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher