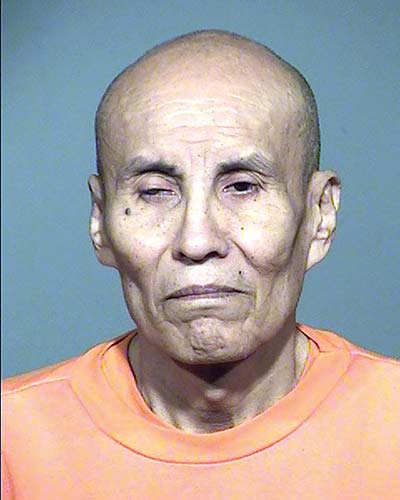

WINDOW ROCK, Ariz. A Navajo man convicted and sentenced to death in Arizona for a 1978 sexual assault and murder is schedule to be executed on May 11.

Lawyers for Clarence Wayne Dixon, 66, originally from Fort Defiance, say the scheduled execution violates the Eighth Amendment because he is mentally incompetent. He was also declared legally blind in 2015.

[NOTE: This article was originally published by the Navajo Times. Used with permission. All rights reserved.]

The Eighth Amendment bars cruel and unusual punishment and forbids the execution of people who have an intellectual disability.

On April 8, his attorneys filed a challenge against the Arizona Board of Clemency and Arizona Gov. Doug Ducey, citing that the board is comprised mainly of former law enforcement officers. As a result, Dixon, a 1974 Chinle High graduate, would not receive a fair hearing.

According to court documents filed by Dixon’s attorneys, the Board of Clemency is comprised of Mina Mendez, Salvatore Freni, Michael Johnson, and Louis Quinonez, three of which are law enforcement officers.

Dixon is being held at the Arizona Prison Complex in Florence, Arizona. He was sentenced to seven consecutive terms of life in prison for sexual and aggravated assault and kidnapping of a Northern Arizona University student in 1987.

In 2002, DNA collected from a 1978 murder of Arizona State University student Deana Lynn Bowdoin matched his DNA. He was indicted on one count of first-degree murder and one count of first-degree rape.

Investigation

Under the DNA Identification Act of 1993, Dixon’s DNA was collected in prison. The act authorizes the FBI to establish an index of DNA identification records of persons convicted of crimes and analyzes DNA samples recovered from crime scenes and unidentified remains.

His DNA was matched against the semen samples collected by Tempe police, which investigated Bowdoin’s case.

Dixon’s attorneys say experts who provided written testimony and interviews say Dixon has had a history of mental illness, including paranoid schizophrenia.

In 1977, Dixon, who was studying engineering as an Arizona State University student, was arrested for assault with a deadly weapon after he hit a 15-year-old female – whom he told a psychiatrist reminded him of his now ex-wife – over the head with a metal pipe.

According to court documents, the teenage victim told police that Dixon approached her and said, “Nice evening, isn’t it?” before striking her. After assaulting her, the victim said Dixon returned to his vehicle.

Maricopa Superior Court Judge Sandra Day O’Connor had court-appointed psychiatrist Otto L. Bendheim interview Dixon.

Bendheim and Maier Tuchler, a psychiatrist, deemed Dixon was not competent to stand trial. O’Connor found him not guilty by reason of insanity.

Two days before Dixon was remanded to a state hospital to receive treatment for his mental illness, he raped and murdered Bowdoin, according to court records filed in the Pinal County Superior Court by Dixon’s attorneys.

Court records do not specify if he killed Bowdoin first, but Dixon was arrested for burglary and assault on a woman not long after being found not guilty of assaulting the 15-year-old victim.

He was subsequently sentenced to five years in prison, which he served from September 1978 to March 1985, for the burglary and assault charges.

Three months after his release from prison in 1985, he committed another felonious crime in Flagstaff.

Assault of NAU student

Court documents state Dixon was on probation and living with his brother when he sexually assaulted a Northern Arizona University student.

The victim provided a physical description of him, after which NAU campus police sent out an area-wide “attempt to locate” call.

Flagstaff Police Officer Michael Terrin located a man alongside Interstate 40 fitting Dixon’s description, holding a sign reading “Albuquerque.”

During an interview, Dixon told Terrin he had done prison time. Further investigations ultimately led to Terrin arresting Dixon, and he was charged with sexual and aggravated assault and kidnapping.

Dixon would ultimately fire his court-appointed public defenders and represent himself. He was found guilty and convicted and received the seven consecutive terms of life in prison sentences in 1987.

In 1995, under the DNA Identification Act of 1993, Dixon was required to provide his DNA, eventually matching the DNA collected in 1978.

Dixon was already in prison for the rape and kidnapping of the NAU student when a jury gave him the death penalty for Bowdoin’s murder and rape.

Experts, including Bendheim and Tuchler, concluded Dixon should have begun receiving help for his mental illness after his arrest in 1977.

In 2012, John Toma, a licensed psychologist, wrote a 25-page report on Dixon. In it, Toma wrote Dixon never received psychiatric care in 1978. He agreed with Bendheim and Tuchler that Dixon suffered from a psychotic disorder.

“He would have been, at the time of the murder of Deana Bowdoin, in the early stages of a schizophrenic disorder,” Toma wrote in 2012.

Jon Sands, a federal public defender and one of Dixon’s attorneys, wrote on April 8 that the clemency board often breaks its clients’ due process rights. Sands noted that more than two members “from the same professional discipline” violated Arizona law.

“As a result, the respondents, in their official capacities, are acting in excess of their legal authority under Arizona law,” Sands wrote in the April 8 lawsuit.

Sands also filed a motion to determine his mental competency.

Mentally incompetent, legally insane

Previously, an Arizona court determined that (Dixon) was mentally incompetent and legally insane and that Dixon has a documented history of delusions, auditory and visual hallucinations, and paranoid ideations.

Sands refers to Dixon’s court filings that he claimed his DNA was illegally collected by the NAU police, resulting in consecutive terms of life and the death penalty.

“He ultimately believes that he will be executed because the NAU police wrongfully arrested him in 1985. The judicial system – and actors in it, including his own lawyers – have conspired to cover up that fact,” the motion read. “It would offend humanity to execute Mr. Dixon.”

On Feb. 17, 2022, Dr. Lauro Amezcua-Patino asked Dixon during an evaluation if he was aware the state filed for a date of execution.

“Sometimes, I feel a tinge of fear. Other times, I feel a sense of relief. I have been locked up for 35 years. I am reaching the endpoint,” Amezcua-Patino wrote what Dixon said to him.

Amezcua-Patino asked him how he was different now before his incarceration.

Dixon responded: “Back then, I was beginning my adult life. And I had no value. I didn’t attach any value to it.

“Now, I am an older adult male,” he said. “I know I only have a few years to live. I’m not all that. I’m not ambitious. I’ve wasted my entire adult life in prison.

“If I get out,” he said, “I just want to enjoy the days when I enjoy the people I come in contact with.”

Sands wrote that Amezcua-Patino indicated Dixon suffered from persistent delusions related to his legal case and “seeing dead children watching him” since being declared legally blind.

Death penalty

According to the Marshall Project, Joseph Wood was the 1,385th person executed in the U.S. since 1976, the 37th person executed in Arizona, and the 1,210th person executed by lethal injection. Wood died July 23, 2014.

Arizona law states Dixon can select the gas chamber as his preferred method of execution, but he must decide at least 21 days before May 11. If he does not decide, a lethal injection will be used.

The Clemency Board and Ducey have 20 days to respond to Dixon’s lawsuit.

The Navajo Nation has historically opposed the death penalty.

When Lezmond Mitchell, a Diné, was executed on Aug. 26, 2020, Navajo Nation President Jonathan Nez said the tribe did not expect the federal government to understand the Navajo people’s customs and traditions of hózhǫ and k’é.

“We don’t expect federal officials to understand our strongly held traditions of clan relationship, keeping harmony in our communities, and holding life sacred,” Nez said in a statement.

“What we do expect, no, what we demand, is respect for our people,” he said, “for our tribal Nation, and we will not be pushed aside any longer.”

More Stories Like This

Native News Weekly (August 25, 2024): D.C. BriefsUS Presidents in Their Own Words Concerning American Indians

GivingTuesday: Groups Making a Real Impact in Indian Country

Monday Morning (December 1, 2025): Articles You May Have Missed This Past Weekend

Native News Weekly (November 30, 2025): D.C. Briefs

Help us tell the stories that could save Native languages and food traditions

At a critical moment for Indian Country, Native News Online is embarking on our most ambitious reporting project yet: "Cultivating Culture," a three-year investigation into two forces shaping Native community survival—food sovereignty and language revitalization.

The devastating impact of COVID-19 accelerated the loss of Native elders and with them, irreplaceable cultural knowledge. Yet across tribal communities, innovative leaders are fighting back, reclaiming traditional food systems and breathing new life into Native languages. These aren't just cultural preservation efforts—they're powerful pathways to community health, healing, and resilience.

Our dedicated reporting team will spend three years documenting these stories through on-the-ground reporting in 18 tribal communities, producing over 200 in-depth stories, 18 podcast episodes, and multimedia content that amplifies Indigenous voices. We'll show policymakers, funders, and allies how cultural restoration directly impacts physical and mental wellness while celebrating successful models of sovereignty and self-determination.

This isn't corporate media parachuting into Indian Country for a quick story. This is sustained, relationship-based journalism by Native reporters who understand these communities. It's "Warrior Journalism"—fearless reporting that serves the 5.5 million readers who depend on us for news that mainstream media often ignores.

We need your help right now. While we've secured partial funding, we're still $450,000 short of our three-year budget. Our immediate goal is $25,000 this month to keep this critical work moving forward—funding reporter salaries, travel to remote communities, photography, and the deep reporting these stories deserve.

Every dollar directly supports Indigenous journalists telling Indigenous stories. Whether it's $5 or $50, your contribution ensures these vital narratives of resilience, innovation, and hope don't disappear into silence.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Native languages are being lost at an alarming rate. Food insecurity plagues many tribal communities. But solutions are emerging, and these stories need to be told.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Native languages are being lost at an alarming rate. Food insecurity plagues many tribal communities. But solutions are emerging, and these stories need to be told.

Support independent Native journalism. Fund the stories that matter.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher