- Details

- By Kaili Berg

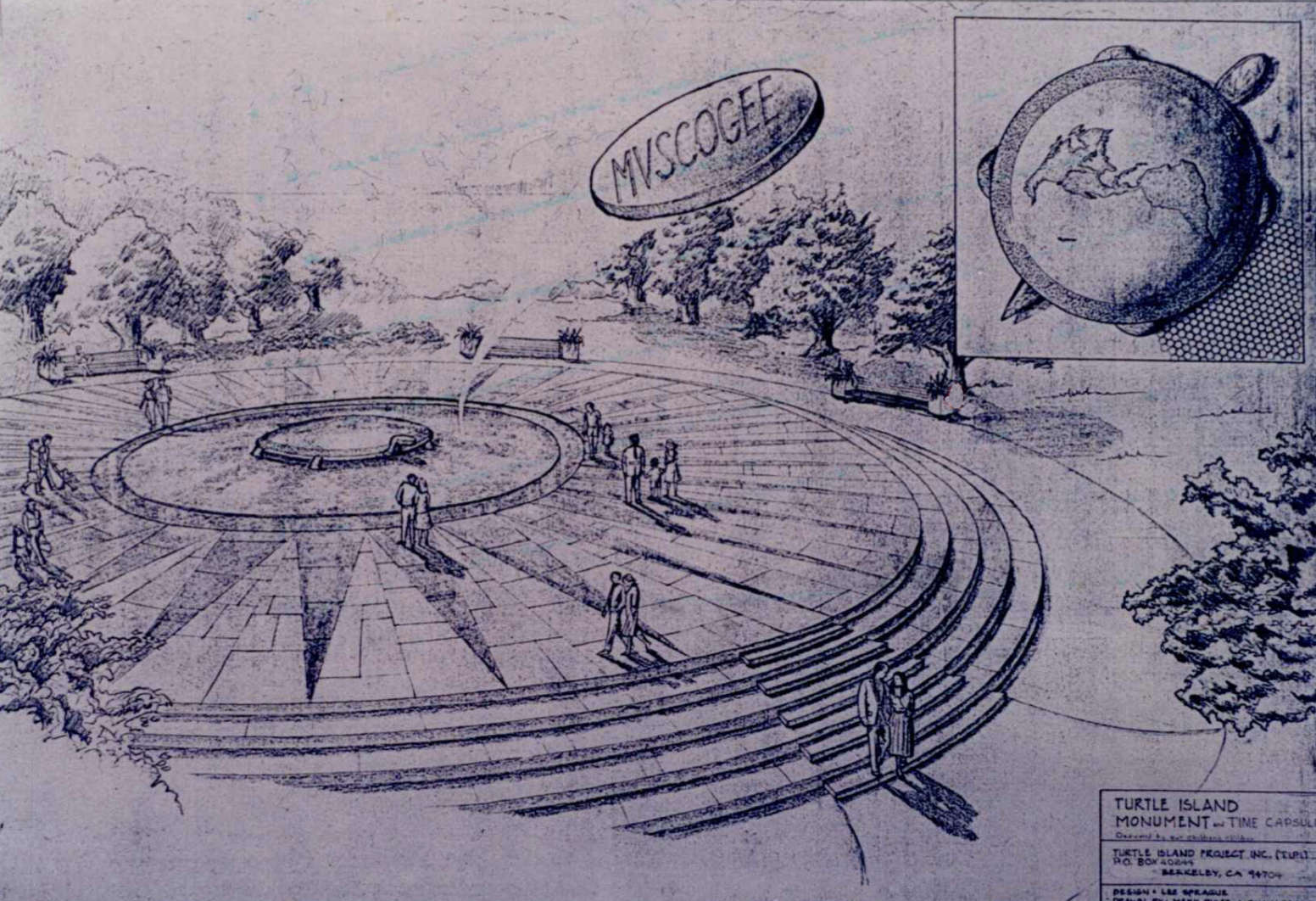

After more than three decades of delays, erasure, and legal battles, Berkeley, California's Turtle Island Monument Fountain is finally close to being built.

Artist Lee Sprague says the project won’t truly move forward until the City gives proper credit to the Indigenous artists who created it.

Sprague, a citizen of the Match-E-Be-Nash-She-Wish Band of Pottawatomi, commonly known as the Gun Lake Tribe, co-designed the monument with fellow Native artist Marlene Watson in 1992. Their concept was selected as the centerpiece for the city’s first-ever Indigenous Peoples Day celebration, the first in the nation.

The design features a large turtle bearing North and South America on its back, symbolizing Turtle Island, what many Indigenous peoples call this continent.

“Our original designs connect the Indigenous peoples from Turtle Island to the moment when Berkeley recognized Indigenous Peoples Day, the first city in the world to do so,” Sprague told Native News Online. “Marlene and I worked with Berkeley residents beginning 33 years ago. We are looking forward to seeing water flowing at the fountain at Civic Center, which has faced 50 plus years of administrative delays. Water is life.”

Despite early support and a $49 million bond measure passed by voters in 1996 that included funds for the fountain, the project stalled for years.

In 2005, the City moved forward without notifying Sprague or Watson and hired a non-Native artist to make four bronze turtles, a move that violated the Indian Arts and Crafts Act, which protects the intellectual property of Native artists.

“The very first time I saw those turtles, I told them that was offensive,” Sprague said. “They completely misrepresented our design. One turtle had just North America on its back, and none of it reflected our stories or our culture.”

The City also credited the non-Native artist as the monument’s creator in official documents.

“That’s the part that still hasn’t been fixed,” Sprague said. “They used our community, our tribal identities, and our traditional symbols and tried to pass it off as someone else’s work.”

Sprague has spent years pushing back, tracking down records, speaking at hearings, and engaging with city officials. In 2020, the City finally reconnected with the original artists, and the monument’s true design was brought back.

Funding through Measure T1 was secured, and the central turtle was restored to the plan. But some documents still incorrectly credit the non-Native artist, and the City must rescind them before construction can move forward.

“I can tell you it’s been hard fought,” Sprague said. “This has taken everything. Elders told me how hard it would be. And they were right.”

Sprague said he and Watson were originally approached by Berkeley citizens who loved their concept, after being turned down by 17 other agencies across California.

“We were working with the community to commemorate 500 years since Columbus. But we always said, he didn’t discover us, we knew where we were. He was the one that was lost.”

Over the years, Sprague says the City continued to mishandle the project, spending public funds, changing designs, and making deals without proper contracts.

One recent offer from the City included a $3 million proposal, but required Sprague to sign away rights that would allow the City to reproduce the monument on merchandise, while barring him from doing the same.

“They basically said, ‘Sign this today.’ I read the contract and said no. They wanted to cut us out again,” Sprague said.

Now, with most major obstacles cleared, Sprague is still calling for one last act of recognition. The City Council must officially rescind the outdated documents that miscredit the work.

“This is about more than art. It’s about respect. It’s about truth,” Sprague said. “There’s nothing like the sense of injustice the way that an American Indian feels when they’re being discriminated against.”

After 33 years, Sprague still believes in the power of the vision he and Watson created.

“Through our art, the unseen powers, the great mysteries, guide our footsteps and recognize Berkeley’s creation of the first Indigenous Peoples Day as a shared dream for generations to come.”

More Stories Like This

Zuni Youth Enrichment Project Takes Top Emerging Artist Apprentices to Phoenix for Artistic Exploration and Cultural ImmersionFrom Dishwasher to Award-Winning Chef: Laguna Pueblo's Josh Aragon Serves Up Albuquerque's Best Green Chile Stew

Rob Reiner's Final Work as Producer Appears to Address MMIP Crisis

Vision Maker Media Honors MacDonald Siblings With 2025 Frank Blythe Award

First Tribally Owned Gallery in Tulsa Debuts ‘Mvskokvlke: Road of Strength’

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher