- Details

- By Neely Bardwell

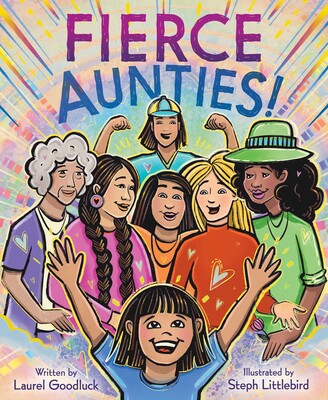

Today, Indigenous author and illustrator team Laurel Goodluck and Steph Littlebird released their new children’s picture book titled FIERCE AUNTIES!, a celebration of what makes aunties so special.

Steph Littlebird, a citizen of the Grand Ronde Confederated Tribes of Oregon, has illustrated before with first book, "My Powerful Hair." Now, with Fierce Aunties!, Littlebird took on the powerful job of illustrating aunties that represent all communities, even including some that reflect aunties in her real life.

Native News Online spoke with Littlebird for a Q&A to discuss why having Indigenous representation in children’s books is important. This interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

What made you want to illustrate for a Fierce Auntie?

Much of my work outside of publishing is about empowering Indigenous women. The work that I'm most known for is actually my Pocahontas series, where I dispel myths about her because of the Disney movie. What I'm rooted in is empowering Indigenous women. It's creating art that I needed as a young Indigenous person that I didn't have.

When I read the the manuscript, I was like, this is for me, this is my chance to honor and show my love for all of the women, not just Indigenous women, but all women who have really uplifted me in my own career and in my own life.

What was the process working on Fierce Aunties?

It was honestly such a cool process. Not every time that you work with a publisher and author, do necessarily feel friendly, but it was a really wholesome process of bringing this together.

It takes about a year total for illustrations. Once the manuscript is approved by the publisher, then they send it to me. From that point forward, you are illustrating. What I do is start with bare bones sketches, just black and white, sketches of my ideas. Once we sort of get through the process of editing each page, which can take months, then eventually you get to the fun part, which is my favorite part, the color. That takes usually somewhere between eight to twelve months. It really just depends on the project and the publisher.

Fierce Aunties! is such an imaginative and whimsical story, so there were lots of illustrations that were fun to make, and that's not always the case. Sometimes stories are more straightforward, but this one has so much whimsy and joy in it. It was just so fun for me, because I just kept thinking about all of these amazing women in my own life that I was sort of illustrating it for.

Is there anybody that you know in your real life that you drew into the book?

Absolutely. It was important to bring in an Afro-Indigenous auntie, because our community has very diverse members, and Black Indigenous people are often underrepresented. I have many Black Indigenous friends, and I also have a friend who is Afro-Latina, but she is also Indigenous. She's always working with young people and teaching them things about the earth, so the Black-Indigenous auntie is teaching them about planting and going on adventures into nature, and that's so her. When I actually showed her the book, she immediately knew that it was inspired by her.

It's so important for people to see themselves in my work, and not just literally another person, but these values that each of the aunts have. I also have a mentor who is not Native, but she is one of the first people who told me that my writing and my art was good enough. So the auntie who is reading to the young girl is very much her, because that person was my mentor.

There's all these sort of underlying symbols in there that I think are really important. I hope I encompassed the world of aunties well because there are so many things that they bring to the table.

Can you tell me a little bit about Deb Haaland’s features in the illustrations?

Deb Holland, she's the first of her kind. She’s the first Indigenous person to run the Department of the Interior, let alone Indigenous woman. She is an auntie archetype. She is out there doing big things. She’s showing younger women what is possible, and that's so important because I didn't grow up seeing that.

Deb is this example of Indigenous excellence, and we need that. We need that so much. She really is one of the most visible Indigenous women. She is making decisions, and was instrumental in bringing attention to the boarding school system while she was in office. Deb is the first person to really push the government to even think about those things.

She is a demonstration of our potential, and she is a demonstration of all the things that we can do and will hopefully achieve in our futures. To me, she is such an inspiration.When I was illustrating I had to make sure she's in there, because she is the one of the most visible aunties in our community.

What does it mean to be an auntie?

I am an auntie of both children that are related to me by blood, but also all of these young women that I have adopted as my nieces, and for me, it's so much about care and recognizing the unique beauty of each child, and trying to help cultivate that. Even though they are not my children, I want them to see their highest potential, and I want them to live inspired lives, and I want them to achieve their dreams.

I get to say inspiring things to them that probably sound less biased coming from me than their parents. When my nieces see me doing good, and they send me love, I send them that love right back. I say all the stuff that I'm doing right now, you're gonna do bigger things in your life, and that's the best part about being an auntie is living as inspiration for them and showing them that what I have is possible for them, and so much more. It's a big responsibility, but it's also the most fun thing, to give love and care for young people and show them their value.

Why do you think it's important for books like Fierce Aunties! to be visible for Native youth and Indigenous girls?

Aunties in Indigenous culture are so important. The idea of the village raising the child, aunties are core to that. What I've learned is that Auntie culture, while it's very important to Indigenous people, is actually something that a lot of people outside of our culture resonate with.

I was actually just speaking with a Black person the other day, and she was like, Oh my gosh, I love the title of this book, because I had so many aunties in my life. All kinds of people will resonate with this book, and think about the women that have been instrumental in their lives.

For me, the book is a love letter to the women who care, who give love to others, even if they're not their own children or their own bloodline. Women are out in this world making sure that each other succeeds and making sure young people do well. This is a beautiful thing. This is so deserved–honoring women and the contributions they give to their community is really important.

What advice would you give to any aspiring illustrators out there?

The big thing that changed my life was sharing my work online and sharing it through Instagram. Gallerists are looking for art on social media, looking for new artists on social media. That is how my agent found my work for my first book.

I've had my Instagram for about 10 years, and in the last five years, it has become where people find me and where people approach me for jobs. I really encourage kids to one, put your work out there regularly, and two, don't agonize over it being a masterpiece. It's really just about creating work and sharing work.

I really encourage Indigenous illustrators to learn a digital art program, and start making your work in that medium, even if you do other stuff. Just start making work in digital because people are looking for it. There is a big demand for Indigenous illustrators right now, and there aren't that many of them.

I'm even working inside my own tribe's community to encourage these skill sets because there are jobs waiting for you, if you can come up to speed on this stuff. You don't have to go to art school to do that, you can literally learn this stuff on YouTube.

The world is your oyster. If you dedicate yourself to your craft and share it with the world, people are going to find you. There are people out there who are looking for your work and ready to love it and celebrate it.

More Stories Like This

Vision Maker Media Honors MacDonald Siblings With 2025 Frank Blythe AwardFirst Tribally Owned Gallery in Tulsa Debuts ‘Mvskokvlke: Road of Strength’

Zuni Youth Enrichment Project and Partners at Ho’n A:wan Productions Launch 8th Annual Delapna:we Project

Chickasaw Holiday Art Market Returns to Sulphur on Dec. 6

Center for Native Futures Hosts Third Mound Summit on Contemporary Native Arts

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher