- Details

- By Rain

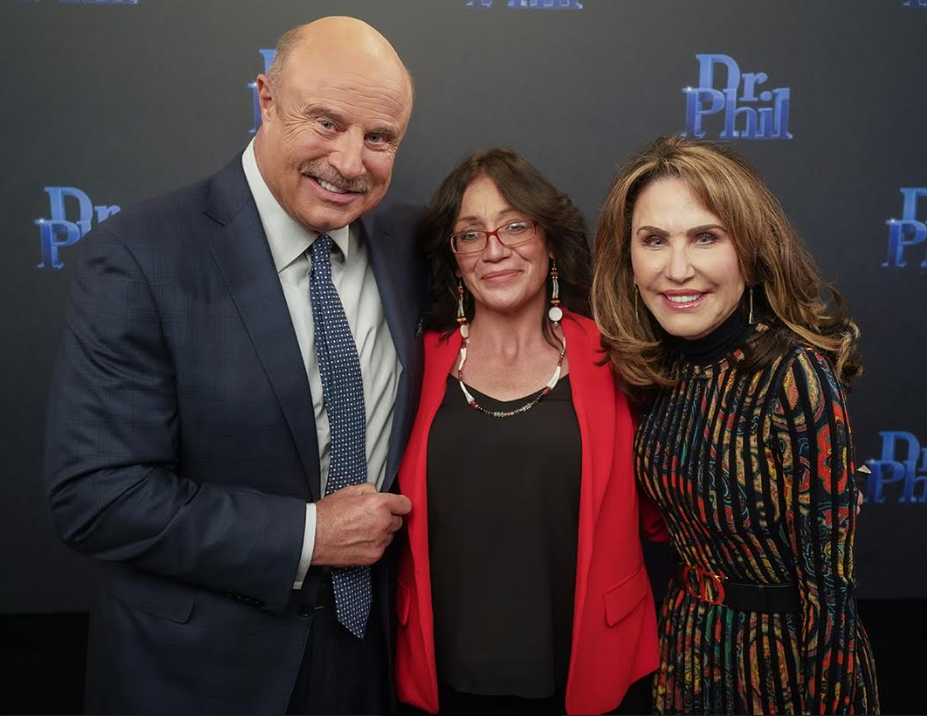

Guest Opinion. “It took a long time to realize, but I don’t think that my daughter is with us today,” Loxie Loring responded when asked by Dr. Phil where she thought her daughter was. The recent episode of his highest-rated talk show exposed a national TV audience to the Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG) crisis. Loxie’s daughter, Ashley Loring Heavy Runner, was last seen alive on the Blackfeet Nation in Montana on June 5, 2017. I was sat next to Loxie on the set, and she gripped my hand as she made that heart-wrenching admission.

Want more Native News? Get the free daily newsletter today.

A few days after the show aired, the third anniversary of the U.S. Senate Committee on Indian Affairs hearing into MMIWG came and went. Ashley’s sister, Kimberly Loring Heavy Runner, testified before the committee on December 12, 2018. She exposed the abject failures of the FBI, Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), and tribal law enforcement in the catalog of incompetence that has passed for an investigation into Ashley’s whereabouts and fate. Kimberly’s testimony elicited furrowed brows, pained expressions, and contrived anger for the cameras from several senators, but has resulted in little else.

In the ensuing three years, Montana junior Senator Steve Daines (R-MT), made positive overtures toward introducing a senate version of the Reduce, Return and Recover Act which the late civil rights icon, Congressman John Lewis, was working on in the House. Should it ever see the floor in either chamber, it will be the most effective and comprehensive MMIWG/MMIP legislation to be voted upon. Daines’ staff made numerous commitments to the proposed legislation in emails, but after November 2020 all respective inboxes fell silent when having secured reelection in Montana with chunks of the Native vote, Daines focused his energy on advancing the Sedition Caucus, not the MMIWG bill.

On behalf of the Global Indigenous Council, Tom Rodgers and I introduced a proposal in February 2019 for a GAO Report on federal law enforcement’s mishandling of MMIWG/MMIP cases. Senator Jon Tester advanced the initiative. Upon the publication of the report in November 2021, Congressman Raul Grijalva, who joined Tester’s petition to the GAO, commented, “The GAO has affirmed what we have known for a long time – that the federal government’s response to the crisis of missing and murdered Indigenous women has been inadequate and lacks a basic understanding of the scope of the crisis,” which is an apt summation.

Since the December 2018 Senate hearing, we momentarily celebrated the tortuous passage of Savanna’s Act, before realizing that Senator Lisa Murkowski’s staff had gutted some meaningful provisions from what remained of former Senator Heidi Heitkamp’s data-oriented bill, fearing that they cost too much to implement. We then welcomed the signing of the Not Invisible Act, limited as it is, but just discovered that the centerpiece of the legislation, the establishment of a “Joint Commission on Reducing Violent Crimes Against Indians,” is only now being formulated by Attorney General Merrick Garland and Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland.

What’s happened with Ashley’s case? In the interim thirty-six months after the hearing, Tom Brady left the Patriots and won a Super Bowl with the Bucs, TikTok stormed social media, a global pandemic has rendered a new normal anything but, in his death throes George Floyd articulated the lived experience and genetic memories of people of color in the American dream, and we barely survived an insurrection that has democracy gasping for George Floyd’s last words. But there’s been no progress in Ashley’s case, unless you count the case file being put on another agent’s desk, and that agent sending Loxie a link to the Operation Lady Justice website. That’s what you get from faux outrage in a US Senate hearing. Nothing.

In October 2021, Chairman Tim Davis of the Blackfeet Nation forthrightly addressed Attorney General Garland, Secretary Haaland, FBI Director Wray, and current Chairman of the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs, Senator Brian Schatz. Chairman Davis timed his letter to coincide with the premiere of the updated version of Somebody’s Daughter. “In Somebody’s Daughter, I demand an investigation into Ashley’s case, and with this letter I reiterate that, with an official request for an immediate investigation into every facet of this flawed case. I also call for a renewed focus and effort to resolve this tragic situation. The Loring-Heavy Runner family has suffered for too long,” he wrote. At the time of writing, Chairman Davis is still awaiting a response from anybody, including from Secretary Haaland.

On October 21, Congressman Greg Stanton (D-AZ) raised Chairman Davis’ letter with Attorney General Garland in a House Judiciary Committee hearing. Garland, clearly caught off-guard, stumbled his way through Stanton’s pointed examination. When asked why the Department of Justice (DOJ) hasn’t lived up to President Biden’s public commitments on MMIWG, Garland’s response, to paraphrase, was that we shouldn’t assume he is doing nothing just because it looks like he is doing nothing. I gave my retort to that at an event with Congressman Stanton at The Heard Museum on December 18. “If it walks like a duck and it quacks like a duck, I’m going to assume that it’s a duck until there is evidence to the contrary.”

Chairman Davis appealed for further direct action from Garland in his letter, “The case of Kaysera Stops Pretty Places, an 18-year-old MMIWG victim in Big Horn County, has disturbing symmetry to Ashley’s case in terms of investigative ineptitude. The 2021 documentary Say Her Name is an exposé on the crisis in Big Horn County, which was made to encourage Attorney General Garland to launch a federal investigation into the situation.” This isn’t hard for Garland to do. Unlike his boss, he doesn’t even have to placate Sens. Joe Manchin (D-WV) and Kyrsten Sinema (D-AZ). If he were to direct such an investigation, it would send shockwaves through every other photo-fit Big Horn County in Indian Country and there’s a high probability that, however begrudgingly, we would see a renewed MMIWG/MMIP investigative urgency. But that’s probably too much to ask when Garland can’t even reply to a Tribal chairperson’s letter.

As it is, we’re left with the Department of Interior’s Missing & Murdered Unit (MMU), the BIA’s new MMIWG/MMIP website, and President Biden’s November 15 Executive Order. The former two aren’t worthy of fanfare. The website is a tip-line with case summaries, and why something so basic took so long to launch is anybody’s guess. To tout that the MMU “builds on” the Trump Administration’s Operation Lady Justice (OLJ) tells us all we need to know. The story of OLJ is in Somebody’s Daughter (1492), and it is enough to state here that at the time it committed $3 million for “law enforcement special initiatives” to support OLJ, the Trump Administration hadn’t blinked at the $120 million that was spent on security so Trump could waddle around his golf courses at every opportunity.

Housed within the BIA’s Office of Justice Services (BIA-OJS), the MMU is “to provide leadership and direction for cross-departmental and interagency work.” Given its history of institutional deficiency, it’s difficult to imagine what that “leadership and direction” could be. If any law enforcement function was deserving of being defunded, it is the BIA’s. It’s ripe to be dismantled, reevaluated, reconstructed, and then appropriately funded so that its officers and agents have the necessary training and resources to serve and protect tribal members, which in its present guise it consistently fails to do.

“I promise you. I promise you. This issue is an absolute priority of mine,” President Joe Biden assured me when I discussed the MMIWG human rights tragedy with him. The President’s MMIWG/MMIP focused executive action reflects much of that conversation, which was subsequently submitted in writing as a “First 100 Days Priority” by the Biden-Harris Tribal Justice Subcommittee. The President adopted those recommendations on cultural competency by requiring “protocols for effective, consistent, and culturally and linguistically appropriate communication with families of victims and their advocates,” but instead of providing for Tribal Liaison Offices in each BIA region, he created a single tribal liaison position within the DOJ. President Biden appears in and has supported Somebody’s Daughter (1492-). I believed the President when he made his promise, and I believe him now. I do, however, doubt some of those on his staff and in his cabinet who advise him.

Every effort to stem the MMIWG crisis should be applauded, but not at the cost of obfuscating from the root causes of the tragedy and continually failing to address those. Despite Savanna’s Act, there is still no accurate accounting of how many MMIWG victims there are, as a law enforcement agency doesn’t exist that will readily participate in interagency cooperation, including agreeing to a uniform method of tracking data. It remains hard to track MMIWG data when your people are still categorized as “other” on many crime and coroners’ reports.

MMIWG is a far more complex and challenging issue than any in the three branches of the federal government appear willing to acknowledge. It is multifaceted, and involves drug cartels, gangs, human trafficking rings, as well as individual and opportunistic perpetrators. All of these are aided and abetted by a legal jurisdictional maze that is yet to be untangled. Interagency law enforcement cooperation needs to be mandated, not subject to “recommendations,” or it will never happen. Violence does not discriminate, and neither should our laws, but they do in Indian Country.

Attorney General Garland should require his army of US Attorneys to uphold their oaths and seek justice for Indian Country victims, instead of acting like Las Vegas bookies and playing the odds on if their cases are strong enough to secure prosecutions. There will be no solution to the MMIWG tragedy without a Congressional fix for Oliphant and a reevaluation of the Major Crimes Act. The paternalistic nineteenth century law is more repressive today than when it was passed in 1885. To “Build Back Better” would be to overhaul that act, and place the emphasis on providing resources, training, and law enforcement infrastructure to Indian Country, which can empower Tribes to address the MMIWG tragedy.

Sometimes, hope is all we have, and I have hoped that our lawmakers grasp the extent of this tragedy, but I remain unconvinced that they do. Lip service doesn’t bring the missing home. Up to this point, every legislative and executive action has been incremental. Like all else before it, President Biden’s executive order doesn’t address extractive industry “man camps,” which remain the nitroglycerin of the tragedy, or human trafficking “tracks” to port cities, which are widely known and have been in operation for decades. The answers the President has commissioned his cabinet secretaries to find already exist in the Reduce, Return and Recover Act. A human rights tragedy of this magnitude demands political courage, comprehensive legislation, and an end to these modest proposals on the periphery of the crisis.

We need to recognize that the MMIWG tragedy was authored in the Doctrine of Discovery. It didn’t begin in the 1990s or 2000s, it began in 1492 with the first documented European contact. Anybody who has read Columbus’s journals and letters knows that to be a historical fact.

My forthcoming book, Psycho/Pathogen, traces the origin of the MMIWG tragedy. Mr. President, I’ll gladly send you a copy. I’ll send you two if you’ll give one to the Attorney General.

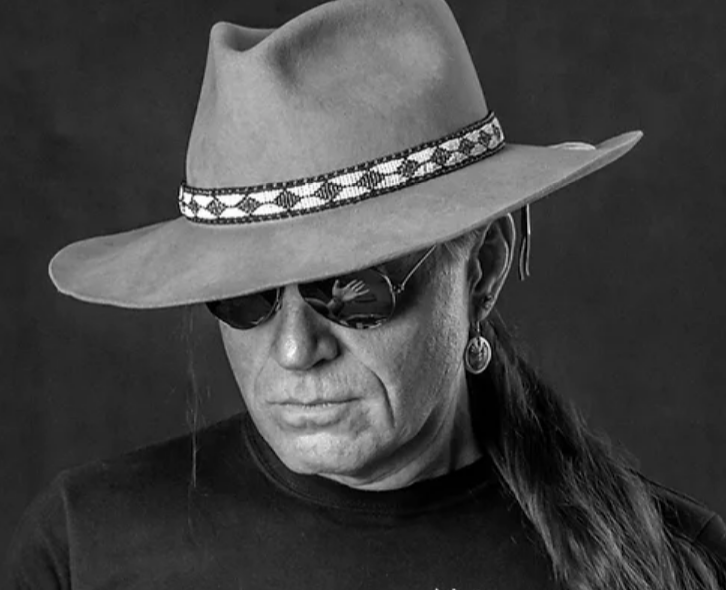

Described by hip-hop pioneer, actor, and cultural icon, Ice-T, as “part poet, part prophet, and all truth-teller,” Rain is the award-winning director of Somebody’s Daughter (1492-) and Say Her Name. President Vicente Fox, 62nd President of Mexico, calls his forthcoming work, Pyscho/Pathogen, “a great, great book.” Described as “essential reading for America’s conscience,” Psycho/Pathogen is summarized by Dr. Maurice Stinnett as “a diary of the COVID-19 pandemic with searing cultural and historic commentary.” Often included in popular lists of “notable Romani people,” Rain is also a member of the Strange Owl family from Birney and Lame Deer, Montana. The name “Náhkȯxho’óxeóó’ėstse” (Bear Stands Last) was bestowed upon him by his late uncle, Don Shoulderblade (1956-2021).

For screenings and information on Somebody’s Daughter (1492-) and Say Her Name visit www.somebodysdaughter.com

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher