- Details

- By Mia Montoya Hammersley - Staff Attorney, New Mexico Environmental Law Center

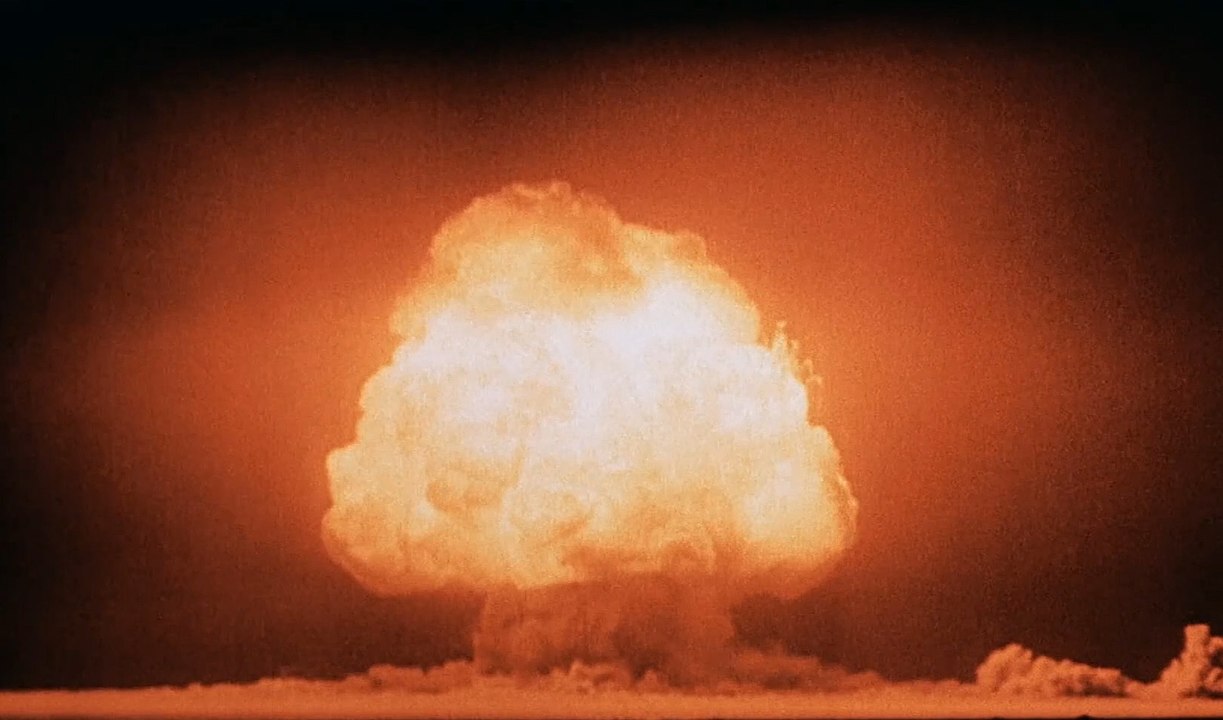

Guest Opinion: Every summer when I was growing up, I looked forward to the time I would spend with my family in Tularosa. A quiet oasis, these weeks were spent picking fruit from the trees in my grandparents’ yard and racing empty banana split boats through the irrigation ditches with my cousins. My grandfather, Demetrio “Dee” Herrera Montoya, served as mayor of Tularosa for many years. He passed away in 2010 after a battle with pancreatic cancer. He and my grandmother were children when the world’s first nuclear weapon was detonated on July 16, 1945, approximately 45 miles from their homes in the Tularosa Basin.

This nuclear test, code named “Trinity” by Los Alamos Laboratory Director J. Robert Oppenheimer, was carried out without the knowledge or consent of the approximately 500,000 people within a 150-mile radius of the blast zone. The blast took place in the White Sands, a place sacred to many Indigenous communities and rich with cultural resources such as the recently discovered 23,000-year-old human footprints. Oral histories from the time of the detonation tell of how ash fell from the sky like snow for days afterward, blanketing entire communities and contaminating crops, drinking water, soil and livestock grazing sites with toxic radiation.

The history of World War II that I learned growing up never included the fact the nuclear bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were preceded by a nuclear test that exposed American citizens, my own family and community, to harmful radiation. The cost was immense; many people lost their lives to cancer, and families struggled with the medical bills and travel required for treatment. In the 77 years since the Trinity test, the U.S. government has never recognized the tremendous harm to the communities enlisted into service of our country without their consent.

Want more Native News? Get the free daily newsletter today.

The Radiation Exposure Compensation Act fund provides compensation to individuals who contracted certain cancers or other serious diseases resulting from exposure to radiation released during above-ground nuclear weapons tests or from exposure to radiation during employment in underground uranium mines. The original RECA is due to sunset in July. However, Senate 2798, sponsored by Sen. Ben Ray Luján, and (the identical) House 5338, sponsored by Rep. Teresa Leger Fernandez, are being considered as amendments to extend and expand RECA. (The House version) recently passed the House Judiciary Committee with bipartisan support. Everyone in New Mexico and the nation should be standing together to ensure these bills are passed.

Over the past 31 years, the RECA fund has paid out approximately $2.5 billion to impacted individuals, while the U.S. government spends approximately $50 billion per year to maintain our nuclear arsenal. The expense of extending and expanding RECA would be nominal in comparison.

As with other environmental injustices, Indigenous communities and communities of color like mine have shouldered the greatest costs of nuclear weapons development, from uranium mining to nuclear testing. To those who believe the Trinity test was a necessary cost to safeguard our national security, the time has come to recognize and compensate downwinder communities for their sacrifice.

Whenever I drive by the White Sands, I can’t help but think about the devastation caused by the Trinity test not so long ago. But I also think of the time spent with my cousins, sledding down the dunes.

Jan. 27 was National Day of Remembrance for Downwinders. Mia Montoya Hammersley is an Indigenous water and environmental attorney, member of the Piro, Manso, Tiwa Tribe and a Yoeme (Yaqui) descendant.

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher