- Details

- By Jenna Kunze

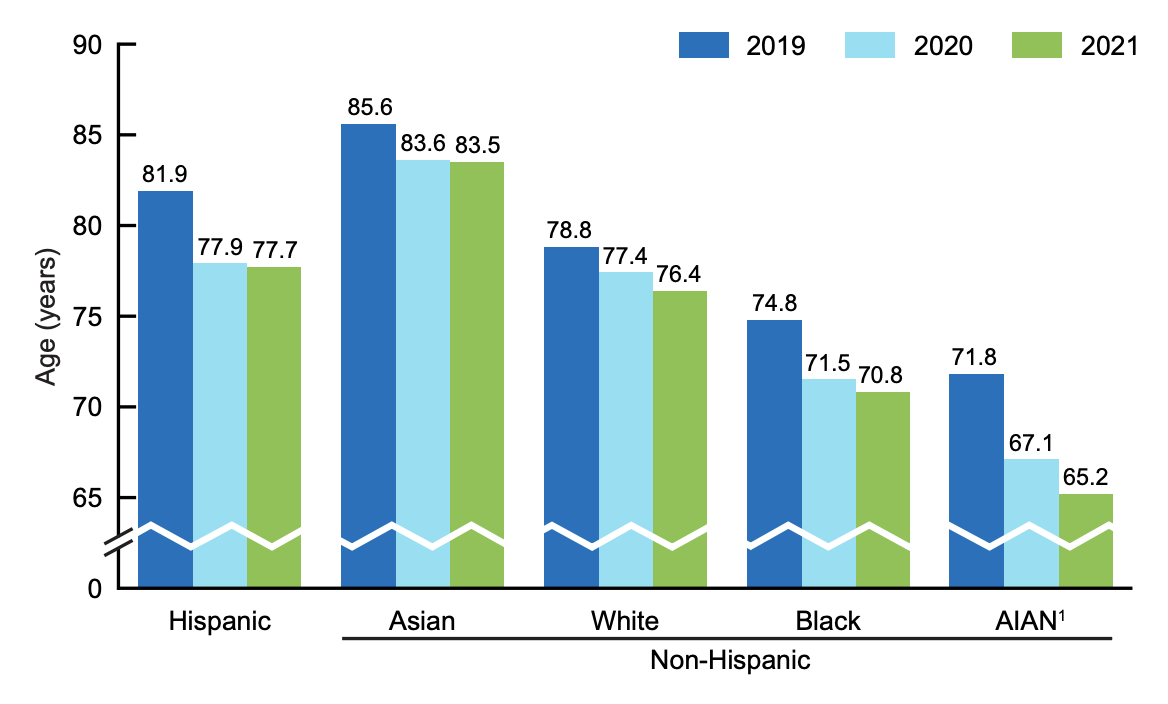

Life expectancy for Native Americans and Alaska Natives declined more than any other race between 2020 and 2021, according to new data from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention.

The decline was mirrored in the overall population: The United States' life expectancy at birth for 2021 was about 76 years, the lowest it has been since 1996. By comparison, Native Americans and Alaska Natives' average life expectancy fell from about 67 years old in 2020 to 65 in 2021, combined with the reported four-year drop the year prior to a cumulative six year reduction in life expectancy.

The data shows the decline in Native communities was due primarily to increases in mortality due to Covid-19 — which impacted Indigneous peoples more than any other race — as well as unintentional injuries, chronic liver disease and cirrhosis, suicide, and heart disease.

“There is no doubt Covid was a contributor to the increase in mortality during the last couple of years, but it didn’t start these problems — it made everything that much worse,” Dr. Ann Bullock (Minnesota Chippewa Tribe) told The New York Times. Bullock is the former director of diabetes treatment and prevention for the Indian Health Service.

Preexisting health disparities — including disproportionate levels of diabetes and obesity —brought on largely by colonization and ensuing cycles of poverty have resulted in more deaths among Native people who contracted Covid than their counterparts. Although more Native people were vaccinated than Black or Hispanic people, CDC data shows they died of Covid at higher rates than any other racial group.

Additionally, barriers to healthcare services due to underfunded government services and remote tribal communities put Natives at a disadvantage. The Indian Health Service provides health care to 1.6 million American Indian and Alaska Native people.

Yet, according to an analysis done by the US Government Accountability Office, it spends less than half on a per-person basis compared to other federal health programs (Medicare, Medicaid, and the Veterans Health Administration).

“How can somebody think this is not a problem?” Loretta Christensen (Dine) IHS’ chief medical officer, told the New York Times. “Yet it’s become normal.”

More Stories Like This

Chumash Tribe’s Project Pink Raises $10,083 for Goleta Valley Cottage Hospital Breast Imaging CenterMy Favorite Stories of 2025

The blueprint for Indigenous Food Sovereignty is Served at Owamni

Seven Deaths in Indian Country Jails as Inmate Population Rises and Staffing Drops

Sen. Luján Convenes Experts to Develop Roadmap for Native Maternal Health Solutions