- Details

- By Aaron Kushner, The Conversation

A recent decision by the Cherokee Nation’s Supreme Court struck down a law that freedmen – descendants of people enslaved by Cherokees in the 18th and 19th centuries – cannot hold elective tribal office. The ruling is the latest development in a long-standing dispute about the tribal rights available to Black people once held in bondage by Native Americans.

National media reported this news as a victory against racism in the tribe. “Cherokee Nation Addresses Bias Against Descendants of Enslaved People,” reads a representative headline from The New York Times.

[This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.]

But as a scholar of Cherokee law and history, I argue this development can be seen another way: as only the latest chapter in a long struggle between the Cherokee Nation and the federal government over which has the power to determine who should be considered a tribal citizen, and which culture’s values should be most important in that determination.

Status of freedmen

On Feb. 22, the Cherokee Supreme Court struck the words “by blood” from the Cherokee Constitution.

This decision means that the 8,500 tribal descendants of Cherokee freedmen can run for tribal office. Freedmen currently have access to voting and other benefits of citizenship that were not a part of this particular decision.

The Cherokee Nation has wrestled with the tribal citizenship status of freedmen since U.S. officials forced Cherokees to adopt freedmen into the tribe in 1866. Part of the tension, as I have written elsewhere, stems from the Cherokee commitment to limit citizenship to those meeting certain eligibility requirements – in this case, those who are Cherokee by blood. For the Nation, keeping citizenship exclusive preserves both Cherokee culture and status as a distinct sovereign entity.

Historically, U.S. officials, often encouraged by public opinion, have wanted Cherokees to adopt U.S. legal and cultural practices. When not attempting to terminate the tribe, U.S. officials have sided with freedmen whenever tribal citizenship disputes reach U.S. courts. U.S. politicians have also repeatedly threatened to withhold federal money should the Cherokee Nation not grant freedmen citizenship.

Origins of a conflict

Before living in Indian Territory – now Oklahoma – Cherokees lived for centuries in the American Southeast. Their society was a collection of towns held together by clan affiliation and kinship bonds.

These clan and kin relationships were the basis of Cherokee social and political life. Their strong communal ethic, with each person playing a particular role in determining the health and strength of the community, supported and was encouraged by the practice of holding land in common; Cherokees did not own land privately.

Cherokees were also intensely spiritual, believing that frequent personal and communal rituals maintained harmony and balance between all living things. Exclusive membership, limited to Cherokees with few exceptions, was one natural extension of their cultural beliefs and practices.

Colonists, later U.S. citizens, wanted to acquire Cherokee land and to make Cherokees more like whites in terms of their religious, government and economic practices. That meant that Cherokees would have to abandon their practice of holding land communally, which made land difficult for U.S. settlers to acquire because they could not deal with individuals.

By the 1820s, Cherokees had adopted many customs and institutions from Americans, including Black slavery, a written language and a constitution. But instead of making the tribe more white – and thereby giving up their lands, as settlers hoped – the Cherokee constitution declared the tribe’s intent to preserve its lands.

Hungry for Cherokee land and the gold in it, and disdaining the Cherokee way of life, Congress in the 1830s gave the president power to force the Cherokee west. Roughly 16,000 Cherokees, along with many slaves, walked the Trail of Tears to Indian Territory – some 4,000 dying as a result.

1866 treaty

Cherokees rebuilt their nation in what is now northeastern Oklahoma. Enslaved Black labor aided this process.

When the Civil War began, the Cherokee first joined the Confederacy. The Nation, however, experienced a schism that led most, including Chief John Ross, the Nation’s leader, to flee to the Union side. Ross’ rival, Stand Watie, and others remained with the Confederates.

After the war, the U.S. forced the Cherokee Nation to sign the Treaty of 1866. The tribe’s 1839 Constitution, affirming previous laws, had stated that Cherokee citizens must be descended from Cherokees, not their Black slaves. But in this peace treaty, Cherokees agreed to make their former slaves full tribal citizens.

This meant granting many who did not share in clan affiliation or Cherokee blood access to tribal services like education and potentially a portion of federal monetary payments.

For many, being a Cherokee citizen was not merely about receiving things from the government – it was also about living the Cherokee lifestyle and dedicating one’s life to that culture. Many Cherokees opposed making freedmen citizens, since most were not Cherokee by blood.

Importantly, they did not want U.S. officials dictating who could be a tribal citizen.

The 1866 treaty stipulated that only freedmen living on Cherokee land within six months of the signing could be citizens. While some freedmen did gain citizenship this way, Cherokees used that provision to deny it to those who did not return on time.

Termination

After the Civil War, U.S. officials, settlers and freedmen made demands on Cherokee land and resources. Freedmen wanted to build a life – most returned to Cherokee territory from surrounding states, as they were not wanted there.

Settlers wanted Cherokee lands. Christian and philanthropic organizations also pressured U.S. politicians to hasten the “civilization” of Indians. This meant forcing them to adopt American economic and social norms – especially private land ownership.

The federal government used freedmen’s petitions for Cherokee citizenship to undermine tribal authority. Freedmen who wanted to live among the Cherokee but were stymied by tribal leaders appealed to the Office of Indian Affairs. Federal representatives, called “Indian agents,” stepped in, superseding Cherokee sovereignty, giving freedmen (and white settlers) Cherokee land.

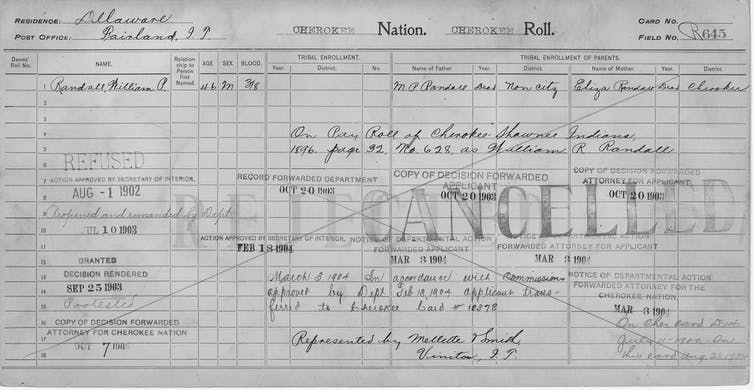

Congress forced the conversion of Cherokee communal lands into individual lots in 1887 with the Dawes Act. As part of this process, U.S. agents counted those living on tribal land – creating the Dawes Rolls, which divided the inhabitants into three categories: Cherokee, white and freedmen.

Congress’ ultimately successful goal was to dissolve tribal governments, freeing up land for new American cities and farms in Oklahoma – which achieved statehood in 1907.

Rebirth

In the 1970s, Congress passed legislation enabling Cherokees to re-form their sovereign government, recognized by the U.S.

Cherokees drafted a constitution in 1975, re-articulating their sovereignty, including citizenship requirements.

The Cherokee Nation, 40,000 strong, used the Cherokee Dawes Rolls – excluding the freedmen list – to determine citizenship. Identifying individual Cherokee by blood had become impossible without some arbitrary reference point; they chose the 1906 list that U.S. agents had compiled to reestablish exclusive citizenship as a sovereign nation.

Descendants of freedmen objected to Cherokees not including the Dawes freedmen list too; freedmen had wanted citizenship to gain access to tribal services and suffrage. This became an even greater issue as the Cherokee Nation expanded to 200,000 people in the 1990s.

Cherokees have legally and socially wrestled with whether excluding freedmen was an act of racism or a show of strength against the U.S. for repeatedly denying tribal sovereignty.

[You’re smart and curious about the world. So are The Conversation’s authors and editors. You can get our highlights each weekend.]

Freedmen struggled against the Cherokee Nation for decades to secure citizenship, often getting the U.S. involved. In 2017, a U.S. district judge ruled that the Cherokee do not have the sovereign authority to deny citizenship to freedmen, since they agreed to make them citizens in the Treaty of 1866.

The 2021 decision to strike “by blood” from the candidate requirement is the next step in that process of debating what Cherokee citizenship means – and how to keep it exclusive despite U.S. interference.![]()

Aaron Kushner, Postdoctoral Scholar, School of Civic and Economic Thought and Leadership, Arizona State University.

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher