- Details

- By Shaun Griswold

An emergency authorization from the Blackfeet Tribal Business Council to slaughter 18 buffalo from the tribe’s herd will produce thousands of pounds of meat for community members facing uncertain food assistance during the ongoing federal government shutdown.

In addition, the Blackfeet Fish and Wildlife Department and the Blackfeet Commodity Office are moving ahead with an elk harvest to produce more meat.

“With federal restrictions and the shutdown disrupting vital resources, the Blackfeet Nation is turning to its own natural resources and community partnerships to ensure that families continue to have access to food,” the tribe said in a statement.

These are among many examples of how tribes across the United States are moving proactively to forecast an increase in demand for food aid and to steer some direction forward as confusion and chaos boil over each day the federal government remains shut down. And with each passing day, the shutdown continues to represent another day the federal government fails to meet its treaty and trust obligations to tribes.

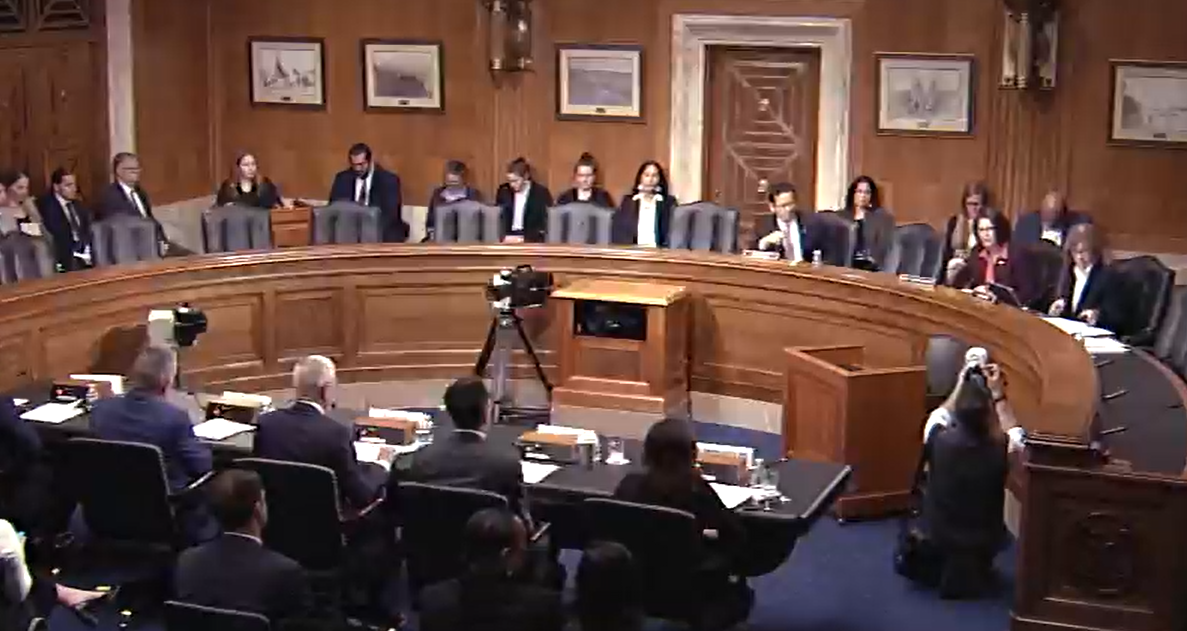

On day 29 of the shutdown, as Congress did not pass a federal budget to reopen the government, members of the U.S. Senate Committee on Indian Affairs heard from tribal leaders about the drastic impact it has caused within Indian Country in education, commerce, food, and housing development.

“Tomorrow we will hit the critical 30-day mark of the shutdown, and our organizations will be facing difficult realities and decisions about the ability to carry out certain programs and whether tribal staff must be laid off,” said Alaska Federation of Natives President Ben Mallott. “A prolonged shutdown places many Alaska Native entities and communities in a difficult and potentially life-threatening position. So please keep in mind that the impacts I raise today will continue to grow until the shutdown ends.”

Mallott said recovery from Typhoon Halong, which hit Western Alaska’s Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta on Oct. 12, is targeted in remote areas without access to roads and hundreds of miles away from where people sought refuge during evacuation. Due to the shutdown, relief efforts are also relying on federal employees working without pay.

“We appreciate these workers’ vital contributions, and we want to see them be paid for their work, including back pay for their unpaid work these past few weeks,” Mallott said.

Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits go to 66,000 Alaskans, Mallott said. While he didn’t give a total number of Alaska Natives who receive the food aid, he said, “The lack of SNAP benefits will overwhelm informal food assistance programs or organizations, such as food banks, in communities where they exist — to say nothing of the impacts for communities where they do not exist.”

Sen. Lisa Murkowski (R-Alaska), chair of the Indian Affairs Committee, said food aid is becoming a lingering concern tied to broader budget issues involving how the federal government funds its obligations to support tribal services.

“There is so much uncertainty that is at play here,” she said.

Murkowski described issues she’s heard about from the shutdown, including smaller tribes worried about running out of reserves that would force tribal employees to go on furlough, work without pay, or be laid off. She said tribes are dealing with unpaid contract support payments, including 105(l) payments on facility leases that the federal government pays to use tribally owned and operated buildings.

“The challenges that come with paying banks when 105(l) and contract support cost payments are not coming in — there is all of this at play that is so challenging and worrisome and, in my view, so unnecessary. There is no good reason for a shutdown ever.”

The Senate committee also heard about the shutdown’s impact on the Indian Health Service (IHS), which benefited from policy gains under the availability of advance appropriations, according to National Indian Health Board CEO A.C. Locklear (Lumbee).

This means that IHS is exempt from shutdown orders and should operate as normal.

“However, not every IHS account was protected,” Locklear told senators. “Several key funding lines, including Facilities Construction, Sanitation Facilities Construction, the Indian Health Care Improvement Act Fund, Electronic Health Records, Contract Support Costs (CSC), and Section 105(l) lease payments.”

Combined, he said, this accounted for $1.3 billion from the IHS fiscal year 2025 budget, including approximately $979 million for CSC and $349 million for 105(l) leases.

“When funding for these lines lapses, tribes face construction delays, halted sanitation projects, deferred maintenance, and gaps in lease payments that threaten operational stability,” Locklear said. “These shortfalls demonstrate that even within IHS, advance appropriations must be expanded to cover the full range of accounts that uphold patient safety, facility integrity, and tribal self-determination.”

Locklear said between 170,000 and 500,000 tribal citizens receive SNAP benefits. “The shutdown has also disrupted nutrition security, which is inseparable from health in Indian Country,” he said. “Any lapse in SNAP benefits would devastate families and deepen existing health disparities.”

He asked the committee to support legislation introduced by Sen. Josh Hawley (R-Mo.) called the Keep SNAP Funded Act of 2025 (S. 3024), which would extend flat funding for fiscal year 2026 and restore any missed payments retroactively.

“The National Indian Health Board strongly supports this legislation and urges swift action to ensure uninterrupted benefits. Food security is health security, and ensuring stable access to SNAP is an essential part of the federal government’s trust responsibility and treaty obligations to Tribal Nations.”

Schools remain open and operational through shutdown exemptions for the Bureau of Indian Education; however, a near-total clearing of employees responsible for directing grants from D.C. to local tribes could have severe consequences.

Kerry D. Bird, president of the National Indian Education Association, said only two people remain at the Office of Indian Education, which is responsible for administering grants from the U.S. Department of Education that can fund services such as heating contracts and curriculum. Tribes cannot contact people in D.C. for a status on payments — either due to offices cleared by shutdown furloughs or more drastic measures. Bird told senators that seven out of nine employees at the Office of Indian Education were processed out of their jobs through reduction-in-force measures.

“BIE schools may struggle to pay for last-minute maintenance costs. And public schools serving Native students may not receive funding from the Johnson-O’Malley Program or Impact Aid, and even face the possibility of Title VI and related funding being severely diminished if reductions in force are fully implemented,” Bird testified.

The flow of money to Indian Country — freezing or potentially going away altogether — is most felt from the Treasury Department ending support for Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFIs). Pete Upton (Ponca Tribe of Nebraska), CEO of the Native CDFI Network and executive director of Native360 Loan Fund, told senators that all CDFI staff at Treasury were issued a reduction-in-force order on Oct. 10.

“If left to stand, the RIF action of Oct. 10 and the ensuing abolishment of the CDFI Fund will cause severe immediate and long-term harm to Native CDFIs’ ability to serve the growing small-business, homeownership, agricultural, and consumer lending needs of tribal communities — needs that have long been ignored by mainstream banking institutions,” Upton said.

He outlined direct market impacts if those positions are lost, including the demise of the New Markets Tax Credit Program and the USDA’s Section 502 Native Relending Programs.

Last week, 105 Republican members of Congress wrote the Trump administration a letter in support of CDFIs, stating that the loans “play an important role in supporting economic development in rural and underserved communities in our states. They enhance the viability of community development projects, especially in rural areas, by offering flexible financing tools such as longer loan terms and interest-only repayment periods.”

“CDFIs are not a partisan issue,” Upton said. “The CDFI Fund and the NACA Program are not handouts — they are a practical fulfillment of those trust and treaty obligations, ensuring Native people have the same access to financial and economic opportunities as all other Americans.”

More Stories Like This

Northern Cheyenne Push Back Against Trump Administration’s Effort to Alter Little Bighorn HistoryFlorida Man Sentenced for Falsely Selling Imported Jewelry as Pueblo Indian–Made

Navajo Nation Declares State Of Emergency As Winter Storm Threatens Region

The Prediction Market Boom is Posing an Existential Threat to American Indian Gaming

NARF Condemns ICE Actions, Says Native Americans Unlawfully Detained

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher