- Details

- By Ashley Minner & Jessica R. Locklear

Following World War II, thousands of Lumbee Indians migrated from their tribal homeland in rural North Carolina to industrialized cities, including Baltimore and Philadelphia.

Seeking work and a better quality of life, they formed distinct Lumbee communities. They brought their foods – cornbread, collards, pastry. They brought their singing and strong work ethic. They became business owners. They founded churches and urban Indian Centers.

Their lives and contributions became part of the historical record and cultural landscapes of these places, but over time, a complex set of factors have resulted in the movement and displacement of the people themselves.

We are Lumbee scholars Ashley Minner from Baltimore and Jessica Locklear from Philadelphia. We have mined local archives in search of our forebears. We’ve found news articles, photographs, maps and even video footage documenting relatives and friends who often have no idea they are represented in collections.

As safeguarders of history, institutional archives necessarily have rules in place to govern access to their collections. Many of the materials are also subject to copyright, and the rights are owned by the creators of the materials or their employers. In other words, a photographer or the company the photographer was working for would own the rights to a specific photograph.

Faced with restrictions as to how the memories we found can be accessed and shared, we ask: Who has the right to the archives? What are our obligations both as tribal citizens and public-facing researchers when we find “our people” in them?

Ashley Minner, Baltimore

When Lumbee Indians moved to Baltimore, they settled in an area on the east side of town bridging the neighborhoods of Washington Hill and Upper Fells Point. The blocks of brick row houses with marble steps looked nothing like the rural home they left behind, but as other ethnic communities had done before them, they made this place their own.

In 2018, I hit the archives in earnest, anxious to corroborate stories shared by my elders about “the reservation” they had formed there in their youth.

They described a landscape intimately familiar to me, where places I grew up – the Baltimore American Indian Center and South Broadway Baptist Church – are still open and operating. But their stories were filled with names of businesses and people I didn’t know because this area has been continually transformed since then.

One of the first and richest sources of documentation I found was the Baltimore News American newspaper photo archive. There were forgotten images of community leaders, legends and even relatives.

My immediate impulse was to share the photos via social media so our people could enjoy them as well. To share them legally, I needed permission from the Hearst Corporation, which owns the copyright, which I eventually got, months later.

In the meantime, I ran into Hannah Locklear, another Lumbee woman from Baltimore. She cried happy tears when I showed her one of the archival images I had saved on my phone. There was her great-grandma, Margie Chavis, young, standing on the stoop of the Baltimore American Indian Center. Along with our memories, images from archives like these are sometimes all that remain.

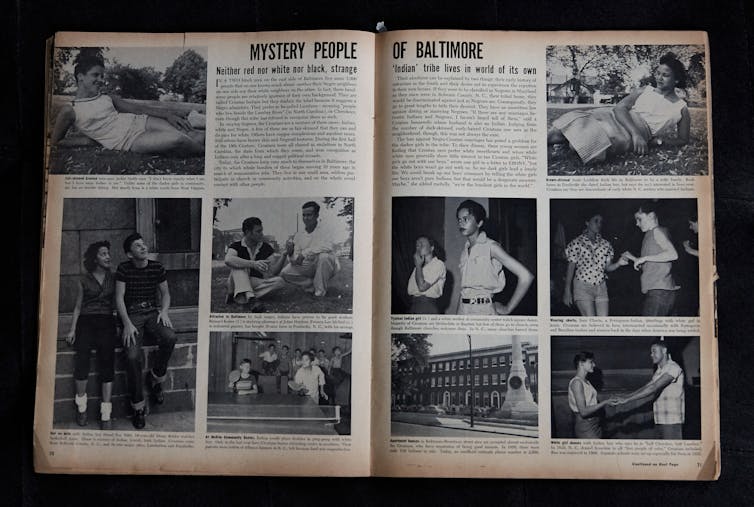

A fellow researcher alerted me to a September 1957 Ebony magazine article – “Mystery People of Baltimore: Neither red, nor black, nor white. Strange ‘Indian’ tribe lives in world of its own.”

A grainy print copy is available at Baltimore’s Enoch Pratt Free Library. I noticed right away that one of the featured photos – taken at a youth social dance and captioned “Typical Indian girl” – was my Aunt Jeanette. Just 14 years old, she was neither interviewed nor told how her photo would be used.

With great celebration, the Ebony and Jet Magazine photo archives were recently donated to the National Museum of African American History and Culture and the Getty Research Institute so they would be “widely accessible to researchers, scholars and the public.” But those archives aren’t publicly available yet.

Incredibly, a copy of the magazine itself was listed in the collections of a London prop shop. I bought it and brought it home to Aunt Jeanette.

She carefully opened the yellowed, oversized magazine and delightedly found a teenage version of herself inside, along with photos of other Lumbee young people, new on the Baltimore scene, playing at youth centers, sitting on stoops, lounging in Patterson Park.

Despite the hurtful context of the article, Ebony managed to capture a special time for our community. These are some of the only images we have of “the reservation” in its heyday.

Unfortunately, they are available only to those who can wait an indeterminate period of time until they’re made publicly available, and then navigate the bureaucracy of the institution where they’re housed.

Jessica Locklear, Philadelphia

Unlike Baltimore, there was no “reservation” in Philadelphia. Here, Lumbees settled in pockets across the city, yet found ways to forge a sense of community. When I started my research, I doubted there would be evidence of Philadelphia’s Lumbee community in any archives. I was wrong.

While searching the archives of the Philadelphia Inquirer newspaper, I found a story about a Lumbee man named Thessely Campbell who was set to star in a 1984 PBS documentary. Campbell moved from Fairmont, North Carolina, to Philadelphia in 1952 and found employment as a welder at the Budd Company.

Obtaining a copy of this documentary was a lengthy process. The closest available copy was at a university library over 320 miles away. “The Work I’ve Done” focuses on Campbell’s retirement, but also documents Philadelphia’s Lumbee community, including footage shot inside the Native American Freewill Baptist Church, where Campbell was a minister.

In 2019, I conducted an oral history interview with Campbell’s wife, Helen. She wanted a DVD copy of the film to keep and share with family. It was at this moment I asked: What is my obligation to pass along material that is available to me, as a scholar, to those who may not be able to access it otherwise?

I felt strongly a copy of this film belonged in the hands of the family represented in it. Asserting a claim of fair use, I made Ms. Helen a copy, and I’m glad I did – she passed away a few months later.

More recently, I stumbled upon a digital copy of the documentary made available by the Internet Archive, a nonprofit dedicated to universal access of archival materials. However, “accessible” does not always mean findable.

In sifting through various archival records, I occasionally find photos of familiar faces, which I try to share with those individuals or families. Most people are tickled to find they are in the archives, and most enjoy being able to view and share images they would not have found themselves.

Accountability in two directions

The renowned Lumbee scholar Malinda Maynor Lowery writes of being “bound by two sets of ethics that overlap heavily: A Lumbee’s obligation demands accountability to the people who have lived history, and a historian’s responsibility demands accountability to the widest possible sources.”

As tribal citizens and scholars doing public-facing work, we consider ourselves similarly bound. We search for “our people” far and wide. When we find them in archives, we feel obligated to bring them home to their families.

Knowing our people will not access archives as we do, through libraries, universities and museum collections, we meet them where they are – in their homes, out in the world, and on social media.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]

Repatriating the archives isn’t always about removing materials from institutional care. It’s making sure the people whose lives and cultures are represented in collections know they are there, and ensuring they have the ability to view and share these materials as they see fit. When materials are returned to their communities of origin, they become reactivated.

If we have the ability to give a woman – or a whole community – the opportunity to disarm a hurtful encounter of their youth, and to allow public affirmation of their beauty and true history, we will. If we can return a walking, talking, preaching, singing father, husband and minister to his people, we will.

We are dedicated to sharing the rich histories of former Lumbee neighborhoods with present generations. Bringing archival materials directly to our people presents opportunities to interact with our shared past – and that informs our future. ![]()

Ashley Minner, Professor of the Practice, Department of American Studies, University of Maryland, Baltimore County and Jessica R. Locklear, Ph.D. Student in History, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher