- Details

- By James Giago Davies, Lakota Times

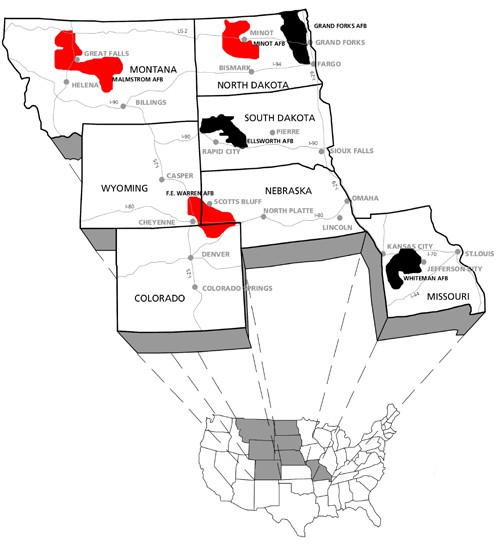

CHEYENNE, WY— Last week the United States Air Force (USAF) met with various tribal representatives at Warren Air Force Base to discuss the upcoming Minute Man Missile construction, and how that construction might negatively impact tribal cultural sites. This meeting was addressed over the weekend at the Great Plains Tribal Chairman’s Association (GPTCA) meeting in Rapid City.

Oglala Sioux Tribal Attorney Mario Gonzalez is perhaps the leading expert on the 1851 Treaty, and how stipulations therein impact any silo construction plans by the USAF.

[This story was originally published in The Lakota Times and is used with permission.]

“All that area down there is our aboriginal area,” Gonzalez told LT. “It’s Cheyenne area, but we used that area, too, so there’s a lot of Lakota sites down there around Cheyenne. There were meetings down there with the THPOs (Tribal Historic Preservation Officers). A meeting was held at Warren AFB with the Air Force, two or three days ago. The Air Force had invited like fifty tribes to come in there and help with the survey.”

Despite the large scope of the invitation, Gonzalez does not find the tribal presence at that meeting adequate. This was expressed a few days after at the GPTCA meeting in Rapid City.

“At the (GPTCA) meeting there was a little concern by the chairmen that they are not being informed about (the Missile Silo construction). They are really concerned that the THPOs are not providing information to the tribes. That was expressed by (OST President) Frank Star Comes Out as chairman of the GPTCA, saying our leadership isn’t being provided information by these THPOs so we don’t know what’s going on.”

In 1966 Congress passed the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) which required federal agencies to evaluate the impact of all federally funded or permitted projects on historic properties. State Historic Preservation Officers (SHPOs) were created to facilitate this process. These SHPOs soon extended their authority into tribal areas where the states had no authority, and they were ignorant of how to identify let alone protect tribal sacred sites. For this reason, Tribal Historic Preservation Officers (THPOs) were created, largely through the advocacy of Standing Rock’s Tim Mentz, who became the nation’s first THPO. Mentz told a Bureau of Land Management (BLM) consultation panel some years back that many archaeologists trample right over sacred rock features and don’t even recognize them. Mentz gave a powerpoint presentation on this concern that so impressed BLM they asked him to come to their main offices and present it there.

“We have every right to say what is important to us,” Mentz said. “The SHPOs have a national group. They were fighting us…saying the tribes don’t have any rights outside reservation boundaries, on tribal land and federal land, to say what is important to them.”

But once THPOs were in play, Mentz said that changed: “We took away from the states as having jurisdiction over anything that had a federal dime, federal involvement, federal attachment, and federal assistance, even.”

Like Gonzalez, Mentz points out that the 1851 Fort Laramie treaty boundary, of 66 million acres, is the express interest of THPOs. The problem, as Star Comes Out pointed out this weekend, is that the THPOs are not informing the tribal chairmen of what took place at the meeting down in Cheyenne, or that there even was a meeting down in Cheyenne, or that this meeting addressed the possible threat to tribal sacred and historic sites, known or yet discovered.

Mentz was the first to uncover the inherent weakness in the THPO system. In over a decade on the job, he became the leading expert on THPOs as well, but his own tribe no longer wants him at THPO meetings. Mentz understands all too well how the THPO can abuse and profit from his position. Instead of protecting the tribe, the THPO draws his THPO salary, he then collects a consultation fee from the archeology firm hired to assess the impact at various sites. The THPO comes to understand if he signs off favorably, he not only collects a fee, any buddies he hires to help him arrive at that favorable assessment, also collect a fee. While many THPOs across the country exemplify THPO purpose and integrity, enough do not that the tribes are not properly informed about the activities or threats of tribal sacred sites on federal land.

The USAF has big construction plans to upgrade 450 Minute Man III missile silos, and they have set up meetings and extended invitations, realizing tribes will take issue with many aspects of that upgrade. But the THPOs have not informed the tribes adequately, and many of the tribal leaders do not know enough about any threat to act effectively without THPO;s running point.

“I had to explain,” Gonzalez said, during his participation at the GPTCA meeting, “that the 1851 Treaty recognized title to 60 million acres but there is also aboriginal Indian title which is based on use and occupation for a long time, all the way to Colorado. We wintered down in those areas. In fact, the treaty says that the Sioux reserve the right to hunt on the Republican fork of the Smoky Hill River in Colorado, as a winter ground, that’s Spotted Tail, he insisted that be in there. Chief Smoke’s people wintered down in the Fort Collins, Loveland and Denver area. I think Chief Smoke even wintered on Cherry Creek in downtown Denver. The state of Colorado is writing the Sioux out of the history of the state. That was a joint aboriginal use area. The Sioux used some of that area more so than the Cheyenne. I explained that to (the GPTCA) at the meeting so they could understand it a little better, why we are involved down there in Cheyenne, Wyoming, why there are meetings held at Warren AFB with the with Air Force, to comply with NEPA (National Environmental Policy Act) and NAGPRA (Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act). NEPA isn’t stand alone, you have to look at it in conjunction with other acts, including NAGRA, ARPA (Archeological Resources Protection Act), including the Endangered Species Act. All of those acts now have to be looked at in conjunction with NEPA itself.”

USAF’s Lt Colonel James Dawkins said, “We’re having to go to those sites that have already have equipment and decommission them, dig some of it away, destroy some of the facilities, and then put new facilities where those old facilities were. And so, this is the challenge. If you’re going to do one per week for nine years, that’s what the average is, that’s quite a big level of work.”

Tribes are concerned that all the digging and destroying might threaten unidentified sacred sites, and the chairmen want their THPOs to be on the ball, not only informing them of the situation with the silo upgrades, but faithfully executing their duties and properly and comprehensively identifying vulnerable sacred sites.

(James Giago Davies is an enrolled member of OST. Contact him at [email protected])

Help us defend tribal sovereignty.

At Native News Online, our mission is rooted in telling the stories that strengthen sovereignty and uplift Indigenous voices — not just at year’s end, but every single day.

Because of your generosity last year, we were able to keep our reporters on the ground in tribal communities, at national gatherings and in the halls of Congress — covering the issues that matter most to Indian Country: sovereignty, culture, education, health and economic opportunity.

That support sustained us through a tough year in 2025. Now, as we look to the year ahead, we need your help right now to ensure warrior journalism remains strong — reporting that defends tribal sovereignty, amplifies Native truth, and holds power accountable.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

The stakes couldn't be higher. Your support keeps Native voices heard, Native stories told and Native sovereignty defended.

Stand with Warrior Journalism today.

Levi Rickert (Potawatomi), Editor & Publisher